Written by a journalist from Lubero, working under a pseudonym because of threats against media by the M23

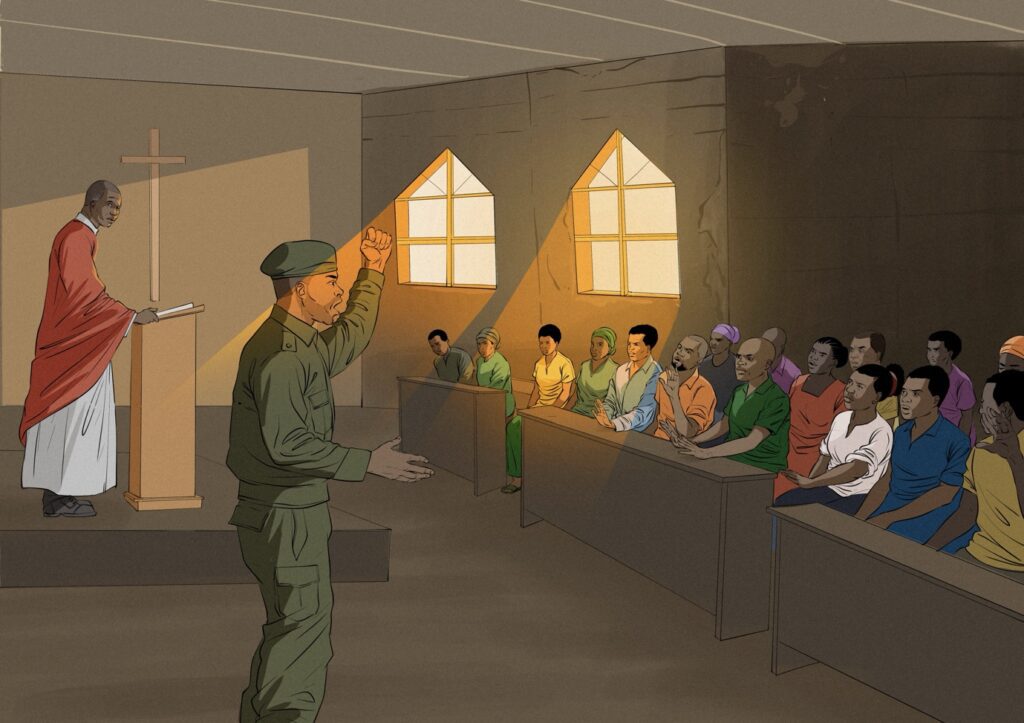

“Do you love us?” asked the rebel leader, standing before a group of young congregants during a confirmation mass in a village in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“No!” the youth shouted back in unison.

Surprised by their response, the rebel leader left the room to fume with his troops waiting outside.

A stunned parish priest, meanwhile, leaned over and gave his congregants a word of advice: In an area where rebels punish dissent, sometimes it can be better to bite your lip, he said.

His caution may have been warranted: In the weeks that followed, the rebels tried to ban youth mass events altogether as punishment for the defiance.

The heated exchange was held in June in a southern part of Lubero territory, where the Rwanda-backed M23 rebel group has taken control since last year – part of a wider insurgency that has seen it displace millions of people across eastern DRC.

Events in places like Lubero — a provincial area close to the border with Uganda — have gone largely under the radar, as media attention instead focuses on the rebellion’s impact on the main eastern cities, which are also under occupation.

But testimonies gathered by a local reporter in Lubero — for a series by The New Humanitarian on M23 rule beyond big cities — paint a bleak picture of rebel abuse and overreach, while also revealing how ordinary people are pushing back.

On top of everyday intrusions like at the church, locals spoke of more serious abuses: civilians forced into labour, and young people arrested or killed on suspicion of belonging to pro-government militias that oppose the M23.

Local journalists, meanwhile, said they had been driven from their homes, and that those who remain are forced to self-censor for fear of losing their lives and livelihoods.

“It is a bona fide police state that focuses only on security and neglects all other areas of life,” said a political scientist from Kirumba, the biggest town in south Lubero. Like all sources in this story, he is not being named to prevent reprisals.

“You’ll see that health facilities don’t have medication, and that teachers are more than five months behind in their salaries,” he added.

Funerals for the missing

Led mostly by Congolese Tutsis, the M23 launched an insurgency in late 2021, citing a broken peace deal and discrimination against Tutsi communities in the east. Since then, however, it has expanded with a political wing that includes national figures who want power across the country.

The movement is supported by thousands of troops from neighbouring Rwanda and is the latest in a line of Rwanda-backed rebellions that stretch back to the 1990s. Kigali is using the M23 to extend its geopolitical and economic influence in the region.

In June, the US government brokered a peace agreement between DRC and Rwanda aiming to stop the fighting, but it has made little difference on the ground, even as US President Donald Trump chalks it up as mission accomplished.

The towns and villages of south Lubero are stark examples of the continuing toll, even if they rarely make headlines – either inside or outside DRC.

Young men said they are especially imperilled, as the rebels routinely typecast them as members of the so-called Wazalendo self-defense groups – militias allied with the Congolese army that operate in the hills and valleys of the Lubero highlands.

A member of a local Lubro youth committee said he knows of “many young people” that have been accused of Wazalendo affiliation. Some were killed on the spot, he said, while others have gone missing.

“For some, we are holding mourning ceremonies, because there is no hope of seeing them again,” he said. “For others, we hope they were forcibly recruited or taken to prison – because that means one day we might see them again.”

A woman in her seventies from Kirumba said her son was taken away when the town was seized by the M23. A father of four, the son was searching for food when he encountered rebels, who identified him as a militia member, she said.

The woman said her son may have been forcibly recruited or killed. “When my grandchildren ask me about their father’s whereabouts, and I have no news, we start to cry,” she said.

One of the missing man’s daughters said she is deeply worried about her siblings’ future. “We lost our father, and life has changed completely,” she said. “He promised he would fight for us to finish school and university, but we have dropped out for lack of fees.”

Forced labour for private gain

Other young men said rebels often requisition them to build barracks, transport equipment, and maintain roads, claiming it as a form of salongo – a communal practice whereby locals help each other with big tasks and neighbourhood clean-ups.

“Any absence is subject to exorbitant fines and even torture,” said a resident of the village of Kaseghe. They said the works are carried out every Thursday under the supervision of M23 officers.

In the village of Pitakongo, men are forcibly rounded up twice a week, often to maintain roads and transport military rations to M23 troops in more distant villages, said a local resident, describing fines and torture for those who refuse.

“Along the way, those carrying heavy loads are sometimes brutalised,” the resident said. “If you resist, you are arrested. With this kind of forced labour, people constantly think about how to leave the area.”

The same resident added that in other villages, rebel-installed local leaders are using salongo and community service as a cover to compel people into forced labour for private gain.

He said people are told they are helping the community – transporting wood for a chief’s fence, for example – but materials are actually sold on for profit. “It is slavery and it has already caused social unrest, but publicly no one can oppose it,” he said.

Human rights defenders and journalists targeted

Human rights activists who spoke about rebel abuses during their advance on Lubero have also been targeted, according to the leader of a civil society group who fled his village for an area under government control.

“They first threatened me, calling me an ally of the government, following my denunciations of human rights violations,” he said. “They then asked me to choose between joining the movement and death. So I decided to leave my village to seek safety.”

The activist said he is now struggling as a displaced person to pay rent and feed his family. “We spend long periods without food supplies, and I have neither a field nor a shop nor any other food resources here,” he said.

A reporter from Lubero who works for the main journalists’ union in DRC said he has two colleagues who were forced to leave their homes after refusing to broadcast messages from the rebels. He said others who stayed behind are self-censoring.

“As soon as the rebels entered, we changed our programming schedules,” he said. “News programmes, talk shows, and programmes dealing with security are no longer broadcast.”

A local radio journalist from another village said his station suspended broadcasts after rebels looted their small studio – taking not just the mixer, computers, and microphones, but even plastic chairs and the mattress they slept on for night shifts.

“We don’t want any martyrs,” said the reporter. “We’ve noticed that we journalists are the most targeted [by the M23].”

UN experts say Rwanda has de facto control over M23 operations, while Human Rights Watch has concluded that it is an occupying power under international law, making it legally responsible for the abuses being committed by the rebels.

The leader of the M23’s political wing, Corneille Nangaa, has recently rejected all reports by human rights organisations of rebel abuse, arguing they are propaganda from the Congolese government in Kinshasa.

The churchgoers who won’t be cowed

Despite the risks of defying the rebels, small acts of resistance persist – like the young churchgoers at the confirmation mass who told the M23, with one voice, that they did not love them.

In that case, the priest quietly told the youth to be careful – warning that the rebels might brand them as Wazalendo and punish them for open defiance. Still, small acts of resistance continued.

The following week, the rebels returned for youth mass, this time trying to compel the congregation to sing songs of praise in their honour, according to people who were present.

In the pews, a young woman refused to stand and sing – to the anger of one rebel, who was moving through the rows to enforce obedience. When he tried to drag her out, the priest stepped in, confronting the rebels and insisting she be left alone.

The dispute didn’t end there. A week later, during an independence day celebration, the rebels returned to announce that they had decided to ban youth mass in the area altogether due to insubordination.

But the same priest defied them again: “You are within my ecclesial jurisdiction,” he said. “If you say there will be no more youth mass, then you should ban all three Sunday masses (for adults, children, and youth), and you will have to tell me to leave.”

Similar acts of resistance in other areas mean the rebels are increasingly wary of any public gathering, said a member of a church outreach group in the village of Miriki.

“All public activities are dictated by the current power-holders, who are not in favour of holding meetings other than their own,” he said. “Intelligence agents are everywhere: They listen, and they infiltrate gathering places.”

A “crisis” for farmers

Residents of different villages said the M23 occupation has also had a severe impact on the local economy and, by extension, their livelihoods.

The situation was better before the rebels arrived because government employees and public sector workers were still paid, which ensured money was circulating, said a teacher from Kirumba.

“Small traders were doing well because their goods sold easily in the villages,” said the teacher. He added that the price of food crops has fallen significantly because of a collapse in demand, creating a “crisis” for many farmers.

“When you go to the market with goods, along the way, you are taxed at checkpoints and once you get to the market, you can’t find customers because people have fled the towns.”

Another farmer in Kirumba who sells cassava crisps – a snack made from slices of deep-fried cassava root – said the current crisis is worse than any of the rebellions he has endured since the 1990s.

“Those who claim the M23 administration is right for us are seriously mistaken – at my age, I have never experienced such suffering,” he said. “We have difficulty providing for our families: feeding them, sending them to school, it’s a real headache.”

A resident of the town of Kanyabayonga criticised taxes imposed by the M23. “When you go to the market with goods, along the way, you are taxed at checkpoints,” he said. “And once you get to the market, you can’t find customers because people have fled the towns.”

In other areas, residents said rebels were barring people from roads leading to their military positions on the outskirts of villages, hindering access to local cropland. Ongoing clashes with Wazalendo groups have also made access to fields dangerous.

“This situation is plunging our families into starvation,” said one of the farmers, whose land is on the outskirts of Kirumba, where clashes have taken place. “It is painful to starve while our cassava rots in the fields.”

The economic situation is so dire that village savings and loan associations — small community groups where members pool savings and lend to one another — are no longer functioning, said the coordinator of one group in Kanyabayonga.

The coordinator said members used to gather weekly, contribute to the pool, and use funds to maintain their fields. But restricted access to farmland and plunging crop prices now make it difficult for participants to contribute and repay loans.

Hospitals bombed and looted

Health facilities in south Lubero are also struggling, as patients cannot pay for care, and because international support has been cut following reductions in US and European foreign aid.

At a referral centre in one village, a nurse said the clinic is critically short of medicine because its primary patron is a “population without resources”. They said patients regularly leave without paying anything.

Elsewhere, health facilities were partially destroyed during clashes between rebels and government forces, which means patients have to travel long distances for care – a major challenge given their lack of means.

A nurse at one health centre said Wazalendo militiamen recently besieged their clinic, demanding $2,000 before it could operate freely. The payment drained the facility’s finances, and today it relies on buying medication on credit.

In a later round of fighting, armed men also looted the clinic, taking mattresses, batteries, solar panels, and medical equipment, the nurse said, without specifying the affiliation of the attackers.

“We have laboratories without equipment, our caregivers are receiving malnourished patients, and we have no supplies,” the nurse said. “We are trying to save people affected by the war without the resources to do so.”

The political scientist blamed the M23 administration for the situation, arguing that it does not respond to people’s needs. “It is only pursuing its mission of conquering territory,” he said. “This creates frustration throughout the region.”

Published first by the New Humanitarian. Editing by Claude Sengenya and Philip Kleinfeld.