Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

“My country has never had leaders who promote all cultures,” predicted Sudanese singer Abdel Karim al-Kabli in 2000. The conflict and ethnic cleansing in Sudan show what this would lead to.

1000 days of war

The sense of superiority of some members of Sudan’s ruling Arab elite is at the root of some of Africa’s most brutal wars. Sudan’s curse is its divisive political class, which exploits the diversity of races, tribes, and religions to pursue a divide-and-rule policy that is proving fatal for the country.

In 2019, artists and youth came together to stand against prejudice during a popular uprising, uniting against oppression in the name of race and religion. Spoken word artists inspired the spirit of revolution at large sit-ins, while rappers fueled the atmosphere of rebellion. For a brief moment, everyone in Sudan was on the same page.

A few months later, the old elite retaliated, and the protesters were shot off the streets by the army and militias. Two years later, the army leaders began a war among themselves, which may well have become the most destructive in the country’s history. “My country has never known tolerant leaders who emphasize all cultures,” Sudanese singer Abdel Karim al-Kabli predicted in NRC in 2000.

He studied rhythms and folklore, uncovering the extent to which Sudanese civilization has become multicultural. “The diatonic scale of Sudanese music is African, not Arabic. It has a strong sense of life, the music of nature. This blend of traditions has come a long way in a country where five hundred languages and dialects are now spoken. Such a colorful mixture creates a beautiful new culture, which is neither Arabic nor African, but Sudanese. We need democratic parties that promote a concept for uniting this diverse country. If we continue on the current path, Sudan will never amount to anything.”

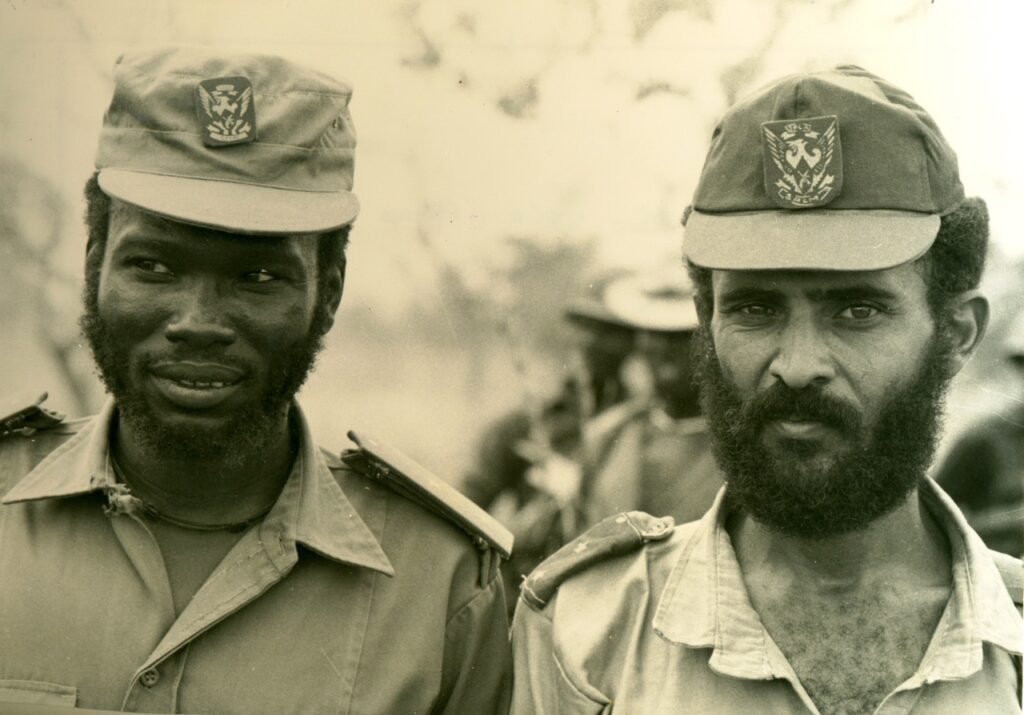

1988 in South Sudan with SPLA Photo Peter Westerveld

The population of Sudan represents a historical blend of brown and black people, attributable to its geographical position between the Arab and African realms. Arabs and Africans have lived side by side in this part of the continent for centuries; most are Arabized and Muslim, with only a small portion being pure Arabs.

Racism in Sudan dates back to the founding of Khartoum in 1821, when the city developed into a trading center for ivory, cotton, and slaves. During the independence negotiations in 1956, the black Sudanese were mostly ignored, and their marginalization continued when most high-ranking positions went to light-skinned, Arabic-speaking politicians and military personnel. They used their influence to dominate the business world and shape the national culture. It wasn’t legal apartheid, as in South Africa, but what was first noticeable in Khartoum was that even after independence, all the street urchins, car washers, and errand boys were black.

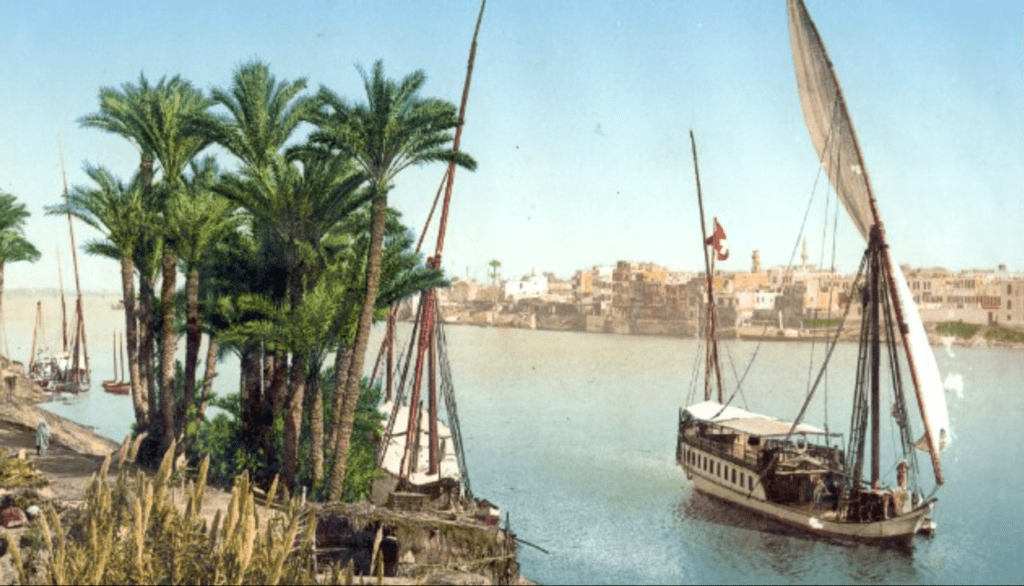

Nile Valley

Condescension

The discrimination against black Africans in South Sudan and Darfur has led to wars, massacres, and ethnic cleansing. The current conflict between warlord Hemedti of the Rapid Support Force (RSF) and president Burhan of the government army is part of a long chain of atrocities. With a disregard for civilian suffering, Sudanese leaders have long waged war against black Sudanese. In the 1980s, prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi deployed militias of Arabized populations to massacre villages in the non-Muslim black south, rape women, and kidnap children as slaves.

In 1987, under the watchful eye of the police near El Daeín, these militias locked hundreds of southern black Dinkas in train wagons and set them ablaze. The RSF, created by the government in 2013, is now pursuing a similar policy of extermination: at the onset of the war, this paramilitary group annihilated 15,000 individuals from the black Massalit in Geneina, and an estimated 3,000 Fur in the Zam Zam camp near Al Fasher earlier this year, while the exact number of victims among the Zaghawa in Al Fasher remains uncertain.

For the vast majority of Sudan’s independent period, military leaders held sway, briefly interrupted by civilian politicians. The civilian administrations were led by the two sectarian parties: the National Unionist Party of the Mirghani family, based on the Islamic Khatmiya sect, and its rival, the Umma, led by the al-Mahdi family of the Ansar sect. During their leadership, Sudan was unable to break free from the cycle of conflict; both sides supported the enforcement of Islamic law, and some research suggests that neither family opposed slavery.

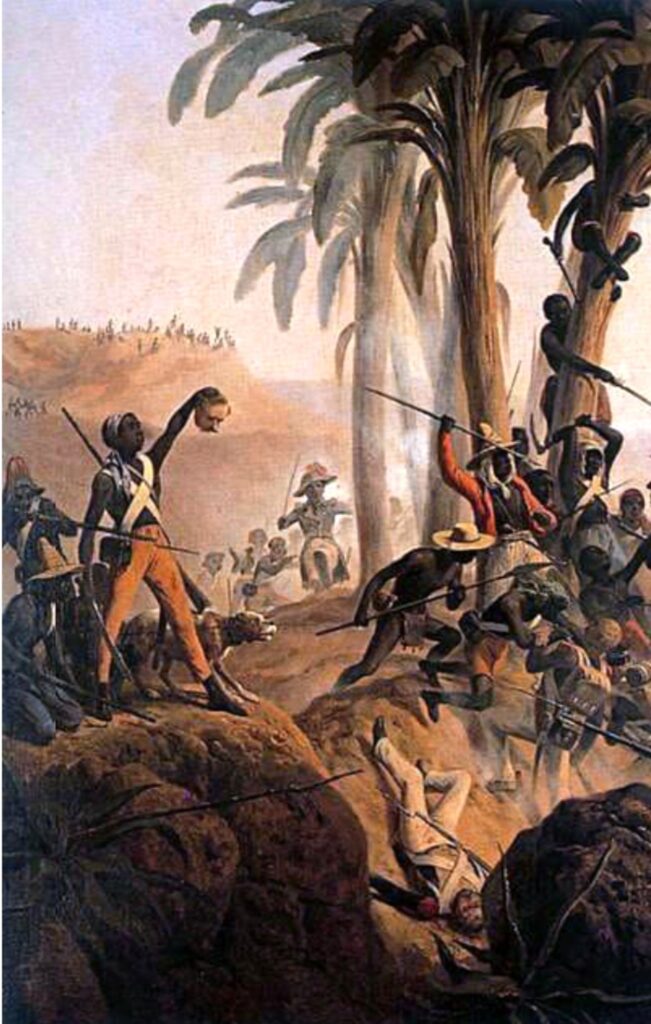

The victory of the Mahdi 1885

Sadiq’s statements, along with those of his political rivals, Mohamed al-Mirghani and Hassan el-Turabi, showed contempt for black people. During a gathering with Christian leaders in the south, the prime minister warned of the annihilation of all the southerners. Being the grandson of the famous imam the Mahdi (the Redeemer), who drove out the British-Egyptian colonizers in 1885, he aimed to emulate his grandfather by taking control of the non-Muslim south and spreading Islam there. “Without Islam, there is no peace,” said the fundamentalist politician Hassan el-Turabi in the 1990s. “Yes, we are trying to spread our Islamist model in Africa, but not through violence,” he lied in an interview with NRC. “Isn’t the American television station CNN also invading my bedroom? Isn’t that an imperialist invasion?”

Bashir in Juba Photo Petterik Wiggers

Military president Omar el-Bashir took his contempt even further. At the end of the 20th century, he referred to black Sudanese as “black plastic bags” that needed to be cleaned up. He was referring to the Christian Nuba’s, against whom he had waged a holy war, and to the refugees from South Sudan in Khartoum. The term was used by his officials and in the media to refer to people from the Nuba Mountains, Darfur, and South Sudan. He called politicians from South Sudan “insects.” “They must be disciplined with the stick,” Bashir argued. The reference to a stick was a reference to a poem by the Arab poet Abu al-Tayib al-Mutanabi, born in 915, who wrote: “You shall not buy slaves without a stick, for slaves are filthy and troublesome.” The educational curriculum in Sudanese schools featured the Lebanese Aliya Abu Mahdi, who stated: “Everything in our country is beautiful… except for the people of a black color.” A street in Khartoum is named after the notorious slave trader Zubeir Pasha, who used South Sudan and Darfur as his hunting grounds around 1874.

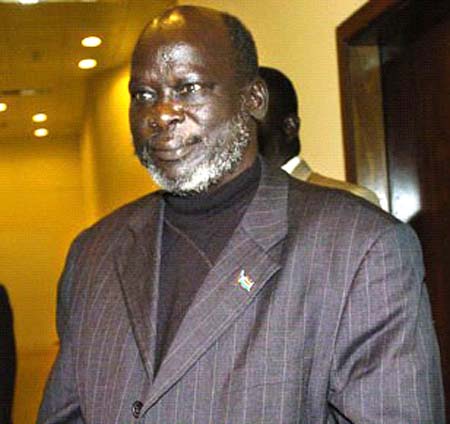

John Garang

In the difficult-to-control periphery of the country, black Sudanese had been rebelling against the dominance of Arabized groups in Khartoum since before independence. The main rebellion in South Sudan was led by John Garang, leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Garang sought a revolution throughout Sudan, not a secession of the south. He coined the idea of ”a New Sudan” and first spoke of “marginalized areas,” such as the Nuba Mountains, the eastern region, and Darfur. He argued that nationality and religion had been used to force a Sudanese identity based on Arabic language and culture, and Islam.

Independence of South Sudan Photo Petterik Wiggers

Garang won the war in the south, but died in a plane crash just before the referendum in 2011. His desire for a united Sudan was torpedoed by South Sudanese voters, who in 2011 voted almost 100 percent against an alliance with the Arabized north. What remained of Sudan continued to struggle with its national identity, as a significant number of African peoples still live in the north.

Hassan al Turabi

‘Making little Arabs’

Arab superiority is reflected in racist vocabulary and sexual violence. The slur “zurug” (blacks) has long been used in the everyday racism of Arabs in Darfur. The term “abid” (enslaved) has been adopted by some Arab supremacists to refer to non-Arab Darfuri. In this context, rape is also prevalent in the current conflict in Darfur. Rape is a means of identity destruction and the ultimate humiliation. “We’re going to make you little Arabs,” the Janjaweed fighters snarled as they committed rape during the war in Darfur in the early 2000s. The RSF, the successor to the Janjaweed, raped hundreds of African Zaghawa girls during the capture of Al Fasher in October last year alone. A similar derogatory perception by the government army and affiliated militias led to crimes against the black Sudanese Kanabi community in the Jezira agricultural region last year.

Suddenly, the religious and racist control of a small group of Arab and Arabized leaders in the Nile Valley appeared to end with the popular uprising in 2019. I have reported on many coups in Africa, detailing the looting and the violent political and tribal conflicts that ensued. However, I seldom saw such unity as I did in Sudan in 2019. The magic of revolution was palpable. The distressed Sudanese, liberated from their fears, perceived the uprising as something extraordinary. There was a unique energy in the air; history was unfolding. “The revolution is about everyone being equal again,” young protesters chanted. To denounce the Arabization of Sudan under Bashir, they added: “This is an African revolution. Sudan is not an Arab country.”

Hundreds of thousands of Sudanese took to the streets. Suspicion among fellow countrymen from different backgrounds had given way to euphoria and brotherhood. I met a jubilant black Nuba who had traveled from the south to Khartoum to express his solidarity, a light-brown Beja man from the east, and a white Sudanese from the diaspora.

These were the happiest days for Sudanese since independence, as if their country had been given a new chance. Women, dressed in trousers, smoked cigarettes in public. Artists came out of their shells and opened studios. Women started playing soccer. The beauty of diversity suddenly shone over Sudan again.

The festive atmosphere around Bashir’s removal shifted to intense anger when Burhan and Hemedti executed a coup together. This is yet another misfortune that has afflicted Sudan since before it gained independence: the military seizing power through force. They are also unaccepting of minority groups and differing views, governing on a limited basis, similar to the sectarian civic parties.

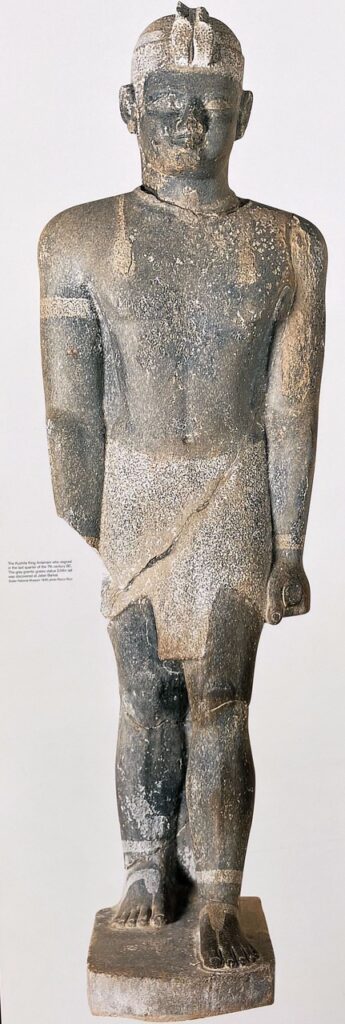

Nubian king Anlamani

Cultural legacy

And so, in 2023, another war began. With a reshuffling of the power blocs. Behind Burhan, Islamic fundamentalists are hiding, working on a comeback. Bashir’s regime was an ideological dictatorship of the Muslim fundamentalists, and they won’t give up the positions they built over 30 years without a fight.

His rival Hemedti’s RSF, acting on behalf of marginalized peoples, pretend to fight against the centuries-old dominance along the Nile. But Hemedti isn’t fighting for a New Sudan, as Garang did back then, but for a select group of Arab or Arabized peoples far away from the Nile Valley. The wars in the south since 1955 may have claimed three million lives, and in Darfur at the beginning of this century, half a million. The atrocities of the current war, the ethnic cleansing, have reached a new low, with likely hundreds of thousands of deaths, millions of people displaced, and infrastructure in ruins.

Singer Abdel Karim al-Kabli had already escaped his home country when the new war began and passed away in America in 2021. He promoted an artistic solution to Sudan’s issues.”Artists are the most sensitive people. They feel the suffering of others more keenly than the victims themselves. More artists should be in power; at least they have feelings.”

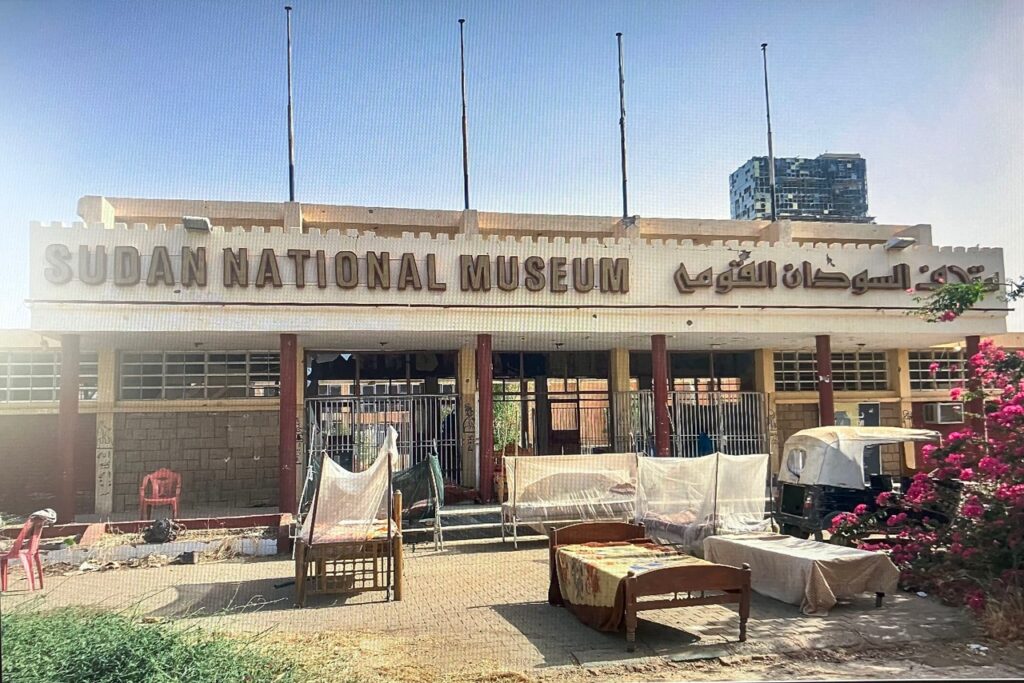

Those who still hoped that a rich cultural heritage could bring people together and heal the schisms within a nation have been disillusioned by the war. The National Museum in Khartoum also suffered from cultural apartheid. Sudan housed the largest collection of historical cultural treasures on the continent after Egypt. This was thanks to excavations in the Nile Valley region where the legendary Nubian kingdom of Kush was located, whose granite statue of King Taharqa (ruler between 690 and 664 BC) ended up in the museum. There were also statues, mummies, murals, and gold ornaments.

Now that it has been looted by the RSF, some Sudanese call it a national disaster; others don’t mourn it. “Those who do mourn it come from the banks of the Nile and still believe in the narrative of the Sudanese state as a unifying force. But that’s a fiction,” said Sudanese analyst Kholood Khair last year to NRC. “The RSF fighters from the Sahel recognized nothing of their own culture and history in the museum and deliberately took revenge,” said Kholood Khair.

Following their removal from Khartoum in April 2025, the RSF desert fighters left their waste in the museum and chopped off the limbs of Nubian rulers. “They did this to settle a score and to show their contempt for Sudan’s centuries-old center of power in the Nile Valley.”

Thus, Sudan continues to wait for a true Savior, not a Mahdi, but a Mandela, who applauds the beauty of diversity.

A version of this story was first published in NRC on 10-1-2025