Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Winding rivers make their way through the rainforest. A fisherman casts his net into the steaming brown stream. “U-aah, u-aah” comes from the river’s edge, primal sounds of the Pygmies in the jungle. This is one of oldest communities in Africa, dating from the times when people lived solely by hunting and gathering plants. The Pygmies, or BaAka as they call themselves in the Central African Republic, live in the Congo basin along the equator.

The visitor must first be cleansed of bad village spirits. The BaAka never used to live in villages but rather stayed with their family throughout the year as nomads in the jungle. There they felt safe and secure and had enough food. After their expulsion from the forest by loggers, poachers and farmers, village life meant deep poverty, alcohol and discrimination. The old man Bernard Wewela throws leaves in a circle, the young people begin to beat their branches on the ground. “Buu-uu, buu-uu”, they call. “We drive out the bad energy of the contaminated village life.”

Wewela teaches young people from the village the secrets of the forest during a trip over several days. Wewela resides most of his time in the village. Reluctantly. Because after their dramatic expulsion from the jungle the BaAka live as outcasts, the village life has heralded their demise.

The culture and knowledge of the BaAka are in their dances and songs, in the use of bush medicines and in their stories. Today Wewela teaches hunting. They span a long net in a semicircle around the undergrowth. “U-aa, u-aa wé wé”, they scream to scare the animals out of hiding. But the little deers don’t seem to want to be caught today, so the spirits are invoked again. “Bengo, bengo”. Angrily they hit their branches to the ground. “Yesterday a young BaAka drowned”, says Wewela. “He had used drugs. That is the curse of the village. That’s why we can’t catch anything today”.

The old woman Henriette Memba is an expert in bush medicines and plants. “A good man takes honey home for his family”, she says. A boy cuts a vine, binds the fiber around his waist along with a tree and drags himself upwards. There at the top grows delicious spinach. Memba smirks about the people from outside the forest. Like other BaAka she calls them Bantu. “Imagine! A Bantu cuts the whole tree just to get the spinach. They destroy the forest”.

The BaAka lived here long before the Bantu. About 2500 years before Christ under the Egyptian pharaoh Nifrikare a travelogue mentions “the little people of the trees”. When the Bantu around that time started to fan out from the northwest of the continent, they stumbled on the BaAka and other Pygmies in the forest, and on the San in Southern Africa. The Bantu nibbled on the forests for farmland and hunted wild animals. In the last two hundred years, Muslim slave traders arrived from the north, and followed since last century by white settlers and logging companies. With their guns these outsiders thinned out the wildlife and in their search for gold and diamonds opened up the area with roads and runways.

The last of the invaders who arrived in Pygmies’ area were the conservationists. Led by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the remaining original forests along the border with the Central African Republic, Cameroun and Congo were in 1993 declared the conservation area of Dzanga Songha. The BaAka ended up in a buffer zone outside the reserve, in a world where they are not seen as real human beings. Throughout the Congo Basin an estimated half a million pygmies are left.

Wewela puts a moss-green mat on the forest floor and crosses his old legs. “Previously, a Bantu sacrificed a BaAka upon the death of a chief. We were their slaves”. His pupils interrupt him; the BaAka allow a say for every man, woman and youngster, they consider everybody equal. “The Bantu beat us and pay little or nothing for our work. There is no respect for us, only here in the forest, we are free”. Wewela nods in approval.

The BaAka are not allowed to live in the park itself anymore, except as guide for researchers and tourists. Barthelemy Ngbanda knows all the tracks in the forest. “Our ancestors taught us that a real man never loses his way”, he says. The Pygmies are very small but that is not noticed under tall trees. Ngbanda leads me under trees of more than four hundred years old on a path made by elephants, marching alongside soldier ants with fearsome gripping teeth.

Ngbanda gestures to keep my mouth shut, because we are approaching the gorillas. He clicks his tongue to set Makumba at ease. “I was so happy when Malui gave birth to twins”, he whispers. He talks about the family of 38-year-old Makumba and his new wife Malui. The family of Makumba lives permanently in the company of seven BaAka guards. Every evening when the apes make nests in the trees, guards lay down to rest on the forest floor. “We are still the rulers of the forest”, Ngbanda says proudly.

Terence Fuli from Cameroun is a gorilla researcher. He was born in a completely different landscape, namely the open savannah hundreds of kilometers northwards. He shows great respect for the knowledge of the BaAka. “They taught me footprints and animal sounds. They recognize every individual tree”, he says. “Without the BaAka we never could find the gorillas, protect and study them. BaAka taught me love for the forest. What I miss here is that I never see the sun rise”.

Towards the evening the rain prepares to come. Gusts of wind sweep over the forest, trees begin to bend allowing wild mangoes to fall. Nowhere in the world can lightning be so intense as above the Congo Basin. Branches break and screaming gray parrots fly away. On the path out of the forest we need a machete to cut our way through fallen trees.

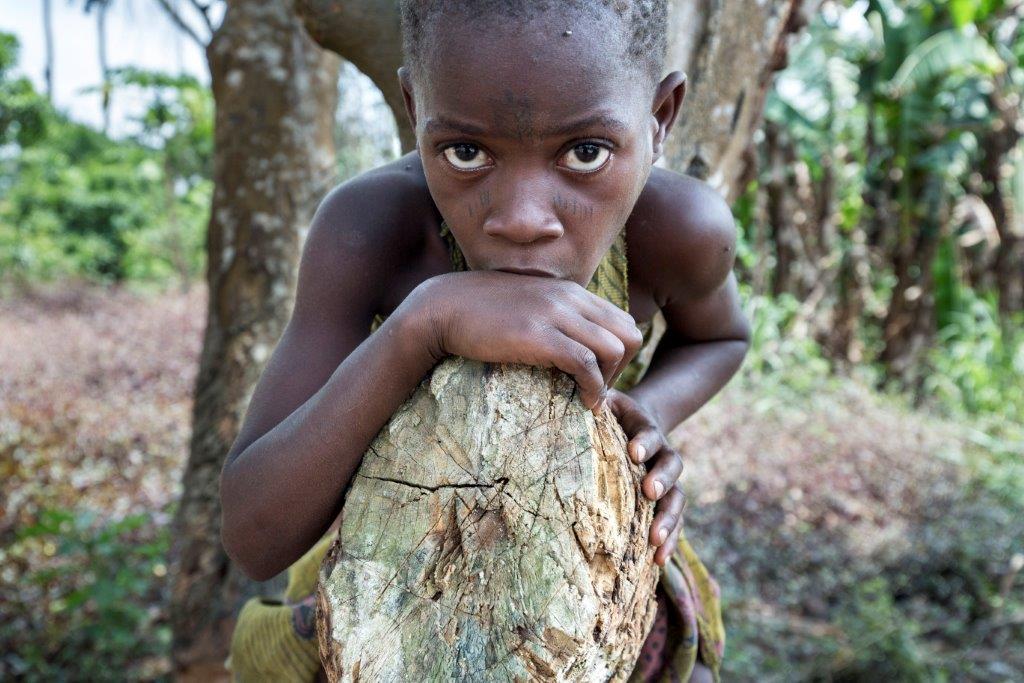

The choice between the village and the forest no longer exists for the BaAka. Forced by circumstances they live most of the year in villages. In the village of Babongo at the edge of the park they hang around aimlessly. Babies with runny noses cling to their emaciated mothers. Nobody wears shoes, their feet eaten by sand fleas, their hair discolored by vitamin deficiency and their bellies distended by food shortages. One of the most ancient people in the world has now become a scrapheap of humanity.

“It is better to live separately”, says Gabriel Mableli, the BaAka chief of Babongo, “because a good Bantu is an exception”. Bantu and BaAka in Babongo live separately, each with its own chief. The Bantu chief is Jean Pierre Pontchon. He says: “My father used to own a BaAka family. Yes, until recently we had real slavery. Until recently we sang songs to the rhythm of the whip”.

The social and cultural differences in Babongo are enormous. BaAka are poor and Bantu’s are always better off. BaAka, unable to be good farmers, usually work as cheap labor for Bantu’s.

Eighty percent of them can neither read nor write. Only three BaAka finished their high school since the independence of the Central African Republic in 1960. Their egalitarian attitude separates them from the more individualistic Bantu, their belief in spirits stirs the minds of politicians and priests alike.

“We BaAka are nature people who live from day to day”, Mableli explains. “We can not deal with money and always make debts. In contrast, a Bantu keeps his money hidden in his pocket. But if you do not share, how do you survive in difficult times?”

The humiliation of the BaAka is devouring their self-confidence. Partly for this reason a human rights organization was recently established in the nearby town Bayanga for them. “The Bantu’s consider them as dirty and animalistic”, says the human rights activist Martial Amolet. “Some BaAka wonder if they are less than human. That is the legacy of slavery and the current discrimination”. Amolet daily visits Bantu farmers to tell them that they should not beat BaAka and they need to pay them for labor. “The BaAka are in a precarious situation, they need special protection. It still has not penetrated the minds of all the people that everybody is equal”.

Beatrice Babano has returned to Bayanga after her refuge in the forest where she was taught by Wewela. She feels happy after her trip. “In Bayanga I want to study to become a teacher, in the forest there is always something to eat”, laughs Beatrice, “You have no worries in the forest and you are always with good people.” Soon she will go back. “Soon the season of the caterpillars begins. That’s a feast. ”

Photo’s Petterik Wiggers.

Photo 1: Bernard Wewela teaches how to climb a tree to fetch spinage

Photo 2: Calling the spirits before the hunt

Photo 3 and 4: The BaAka are now the poorest among the poor

Photo “: BaAka child

This article was first published in NRC Handelsblad on 13-4-2017