Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

On the island of Mouchas, an hour sailing from the mainland of Djibouti, lie the remains of pirate tombs. They date from the 19th century. Already then pirates were a threat to cargo ships in the busy Red Sea lane as they brought their treasures to this coral island.

In the blue-green sea container ships with cargo for hinterland Ethiopia lower their anchor. In the sweltering air flies an American fighter plane which has taken off from Djibouti; a ship from Shanghai sails to the port near the Chinese military base. Sometimes the inhabitants of Djibouti can hear the Saudi air force bombing the coast of Yemen.

Nowhere in Africa are there as many foreign bases situated as in the Horn, and especially in Djibouti military superpowers try to elbow each other out. China has recently gained a solid footing there and Saudi Arabia also wants to set up a base. Turkey and the Arab Emirates established their military support points in the neighboring countries of Eritrea, Somaliland and Somalia. Soldiers from all directions of the wind come to this strategic region to combat modern pirates, smugglers, human and arms traffickers and radical Muslims in Yemen and Somalia. Their attempt to control one of the most important seaways is part of a global game of military dominance, by which the barren desert state annually raises millions of dollars. Jokingly the mini-state is sometimes called the International Republic of Djibouti.

Djibouti is at the intersection of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, between Arab Muslims and Ethiopian Christians, along one of the world’s busiest seaways where in the merciless deserts live the most hardened peoples of the planet: the courageous and self-centered Afars and Somalis.

“For centuries everything here has been about trade and business. The inhabitants in this region exploit their strategic position on the Red Sea to the maximum”, says Nassir Fahami, journalist of the official press agency of Djibouti.

Djibouti town is a beautiful old place with pleasant bars around the main Menelik square. Under the arcades of the antique buildings one finds restaurants with Asian, Arabic, African and European cuisine. The international allure and intrigues call up images of 1941 in Moroccan Casablanca as portrayed in the movie with Humphrey Bogard and Ingrid Bergman. Every spy is watching the other informer, foreign secret services listen in to mobile phones and French restaurant owners study their clientele. Residents of Djibouti shrug their shoulders. “We have been used to this for centuries,” laughs Nassir in an Italian pizzeria. “Djibouti is a spy nest, but with not even a million inhabitants we all know each other. We know exactly who spies for what foreign power.”

You must be hardened to live in Djibouti. It almost never rains and it’s always bloody hot, with an average yearly temperature of forty degrees. The main color in the nature is gray and the soil is infertile. Except from watermelons in the mountains there is nothing to grow there. All food, even drinking water, must be imported at high prices.

A soldier in bulletproof vest in a sentry box at the entrance of the US military camp Lemonnier seems to be in a permanent embrace with an air conditioner. In the camp, the black flag flies high. “It indicates that the heat is too dangerous for sport,” says Lieutenant Edward Cartegena. “Only our bread and Coca-Cola we buy in Djibouti, we get all our other food needs from America or from our bases in the Middle East,” says Cartegana.

Like breasts

The US base is located next to the civil airport. When a Hercules takes off, Cartegena lets his military passion flow freely. “Do you not think she is attractive? Just like the shape of a woman. Do you see her belly? And the propellers? They are her breasts”. The soldiers are kind of locked up here. Since a terrorist attack in 2014 at La Chaumière restaurant at Menelik square, they are no longer allowed to leave their base.

Commander Will Moynahan offers an apple pie from the local patisserie. He is the assistant head of camp Lemonnier with 5000 US soldiers. “We have raised our state of readiness after the bombing in October in Mogadishu,” he says(the attack claimed more 350 deaths). The base, which was established after 9/11, is the only American one on the African continent. From a nearby special airport drones take off, as happened after the giant bomb explosion in Mogadishu when Americans took revenge on camps of the Al Shabaab terrorist group. “We are here to achieve Africa’s security,” says Moynahan. Lemonnier houses several military units and also special commando’s operate from the camp to free hostages or attack terrorist camps.

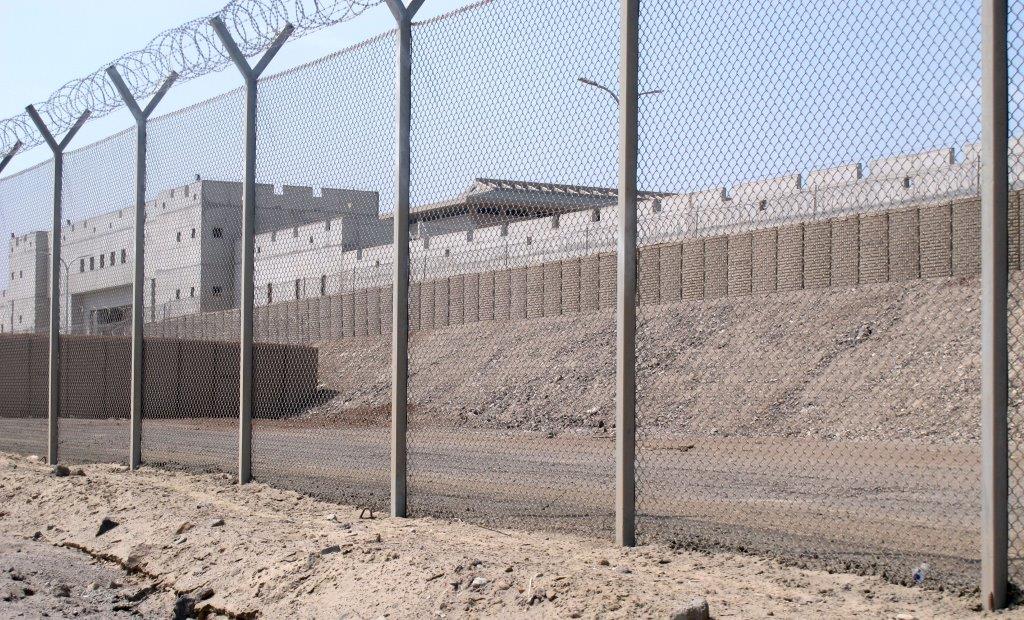

Driving through Djibouti, one stumbles from one to an other military fortress with high-rise walls and barbed wire. In addition to the US, there has been a Japanese base since 2011, the first military presence of Tokyo abroad. There are Spanish and Italian bases and 60 Germans of the international antipirate brigade Atalanta are working in Lemonnier. The oldest military presence is from the French.

A joke of history

The state of Djibouti is a joke of colonial history, a result of competition between superpowers. The French-British rivalry around the Red Sea in the 19th century lies at the origin of this unreal country. The British defended their strategic interests from Aden. In 1862 the French as a counterbalance settled first in the town of Obock and then in Djibouti town. As a protection belt they built fortresses in the rugged mountains and in the stone and sand deserts, to guard against invasions from imperial Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). In the city a French enclave emerged, with wine, baguette, camembert and mineral water from the Ardennes. Only in 1977 did Djibouti gain independence.

But the French remained and Paris signed a defense pact with the independent government. Captain Frederic Graillat scoffs about the black flag on the American base. “We’ve been here for so long and know very well that sports are out of the question during the day. Our presence in Djibouti is entirely different from the other countries”.

Unlike other foreign soldiers, a large proportion of the French soldiers live in the town with their families, they entertain themselves in restaurants and nightclubs and go jogging in the evenings. The French, with their language and culture, did put a stamp on the country, but their influence is waning. Their base is still their biggest in Africa, but with a sluggish number of soldiers, only 1400 soldiers remain now.

Straggler

The French have become a straggler in Djibouti, their global influence fading in the light of the new superpowers. The Chinese in Djibouti do it entirely different from the French and Americans. On a hilltop near the port ten kilometers from Lemonnier they build their most extensive military presence in Africa. Their first base overseas with the high watchtowers really look like a fortress. Two months ago they landed here and will expand their fortress to accommodate 6000 men to become the largest base in Djibouti. Visitors who recently took a short look saw a large hospital under construction for the soldiers. The Americans live on their base in containers, the Chinese build stone houses. Presumably, they also work on underground facilities against spying drones.

The arrival of the Chinese on this strategic intersection caused shock waves with its Asian rivals Japan and India. High American diplomats tried in vain to persuade the government of Djibouti to stop the Chinese coming in. According to the official version of Beijing, the base has “logistics goals”, such as the evacuation recently of fellow countrymen from hotspots of unrest in Yemen and South Sudan. But Western diplomats in Djibouti do not believe that. “The Chinese want to become a military world force, that is why they are in Djibouti,” says a high Western diplomat. “From their base, they can carry out a large-scale armored military attack in the region.”

More than any Western country, the Chinese use “soft power”. They invest for nearly $ 10 billion in Djibouti, and many billions more in economically fast growing neighboring Ethiopia (more than 100 million inhabitants). In Djibouti they build roads, a stadium, a 750-kilometer railway to Addis Ababa, water and oil pipelines, new air and sea ports, a development bank and an industrial park. Recently, a floating Chinese hospital came along with free medical facilities. “The Chinese are the only ones in our country investing in all sectors”, explained president Ismail Omar Guelleh speaking on the Chinese invasion earlier this year in an interview with Jeune Afrique, “only they offer us a partnership for the long term.”

In its sometimes controversial relationship with Africa, China often refers to seven historic naval expeditions from the 17th century to the continent. Perhaps the Chinese involvement with Africa has such a historical precedent, but in the Western vision the Chinese have been engaged in a conquest in Africa since the turn of the century. Since 2010 China has been Africa’s largest trading partner worth over $ 200 billion, it is participating in UN peace missions in South Sudan and Mali, and buys a lot of its raw materials in Africa.

The Chinese also participate in the fight against pirates. Piracy has come down dramatically in the region. The model until a few years back behind this business worth millions of dollars consisted of funders in Dubai and Mombasa, informants in the Red Sea ports and merchants with modern satellite equipment in Yemen and Somalia. What happens offshore escapes internationally accepted laws and regulations. “Warships still patrol, otherwise the piracy would return immediately”, says the diplomat. “Every country combats threats at sea in its own way. If a Chinese ship sees a group of armed hijackers, they may sink the ship”.

Also in the economy of Djibouti the Chinese throw their weight around. The biggest criticism is, like elsewhere in Africa, that Chinese companies hardly hire local labor. “They are taking over everything in Djibouti,” complains a big businessman. “It is nearly impossible to fight it, their competition is deadly.” According to him ministers have expressed privately their dissatisfaction with the growing dependency on China. Most Chinese investments are in the form of loans with a five percent interest rate. “In a couple of years, 80 percent of BNP goes to repayment of loans to China,” he says, “for a poor country like Djibouti, it will be difficult to pay back these loans.”

In other African countries, a dominant Chinese presence sometimes leads to nationalist feelings. But in Djibouti lacks that essential gene of national pride. “We lack these nationalistic feelings to resist a takeover of our country,” says the businessman. “Here it is only trade and money. History repeats itself.”

Photo’s:

1,4,6 and 7 by Johannes Dieterich in 2017

2 Remains of pirate tombs on Mouchas by Yassim Said in 2017

3,5 and 8 by Koert Lindijer in 1991

This article was first published in NRC Handelsblad