Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Back-lit and draped in palm leaves, Abiy Ahmed bears an uncanny resemblance to Jesus Christ in the stickers you see plastered on car bonnets, shop windows and sign boards. The 42-year-old appears equally Messiah-like in his posters, which show him folding Ethiopians in a warm embrace, encouraging them to love one another. Men and women wear T-shirts with his image and the radio plays the praise song “He awakens us”. “Let us forgive each other from our hearts and start a bright new future”, Abiy told parliament after his surprising appointment as Prime Minister end of March. He released tens of thousands of political prisoners and lambasted the state apparatus that tortured them as “terrorist”. He declared Ethiopia’s border war with archenemy Eritrea at an end by saying: “The border has been demolished and replaced by a bridge of love”. Abiy Ahmed’s appearance on the political scene represents something that has been missing for too long on the African continent: a chance for profound change.

The population worships its new prime minister. A spell of euphoria and positive energy has been cast over all. “He deserves the Nobel Prize”, argues young construction worker Bekede, “Abiy Ahmed is young and charismatic, he unites all Ethiopians in ecstasy”. Bekede lives in Bole Michael, a bustling working-class area squeezed between a new highway and the busy airport, deafened by the roar of aircrafts. In the neighbourhood cafe Esther serves coffee, Ethiopia’s national drink. Her husband fled to Canada last year and she was planning to close her coffee-shop this month to join him. “Abiy Ahmed won me round. I am not leaving “, she says resolutely, “I phoned my husband and told him to come home. Thanks to our new prime minister, I can now see a future for us here “.

Abiy Ahmed is whipping through this ancient land of more than 100 million inhabitants like a whirlwind. Ethiopia is the oldest state in Africa with a mythical history, stretching 2,500 years back to when the Ethiopian Queen Sheba returned pregnant from a visit to King Solomon in Jerusalem. The empire was never colonized, but the subjects were trapped in deep poverty, as was demonstrated in 1984 when famine claimed one million lives. Cut off in the highlands, the former dynasty seemed for decades an uneasy juxtaposition of dusty orthodox Church culture, a rigid administrative apparatus staffed by apparent control freaks and Marxist rhetoric.

The big question is whether Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed can really mark the end of an age-old autocracy. His first months in power seem hopeful. His bold decisions have conjured up new realities. “What is happening in Ethiopia is unique in our history and will make the region tremble for some time,” says Abebaw Ayalew, professor of history in the capital Addis Ababa.

It takes time to adjust to the new situation. Freedom is something unknown, a culture of openness is alien to Ethiopia, where compliant behaviour is the rule. During the feudal regime of Emperor Haile Selassie, Ethiopians were not allowed to think, under his successor, the ruthless military Marxist Mengistu Haile Mariam, nobody dared express his opinion and under the government of Meles Zenawi, who came to power in 1991 after a guerrilla war, the population was allowed to have a view if it did not differ from that of the ruling ‘vanguard party’, the Ethiopian Democratic Revolutionary Popular Front (EPRDF). For a brief moment in 2005, elections offered hope for substantive change, but when the EPRDF appeared to be losing, the government party cracked down on all opposition and branded critical journalists terrorists.

A meeting with the blogger Befege Hailu (38) in a hotel lobby in the capital Addis Ababa therefore instinctively feels uncomfortable. In the past, a spy would sit nearby and question my interviewee after I had left. “This meeting would have been impossible last year”, Befege smiles triumphantly. He is a member of the Zone 9 collective of bloggers which writes against repression on the internet. In a country bereft of tolerance, that was a dangerous activity and in 2015 he received an International Press Freedom prize from the Committee for the Protection of Journalists.

He was repeatedly arrested. In 2014, Befege was jailed for over a year on charges of terrorism because of his blogs, and jailed again in 2015 after giving an interview to a foreign radio station. That coincided with the upheaval that would lead to the change of power early this year. Ethiopia had become a time bomb, thanks to a combination of factors: the dominance of one ethnic group, land expropriations around Addis Ababa, youth unemployment and above all the government’s uncompromising crackdown of dissent. Encouraged by bloggers like Befege and other digital activists in the diaspora, the popular anger had grown to such proportions that last year the government began losing control. “Young people no longer feared the police bullets,” says Befege, “a revolution was taking place thanks to the power of social media”.

Still, Abiy Ahmed’s appointment was unexpected. The EPRDF consists of four ethnically-based parties. The Tigrayans (6 percent of the population) were mainly in charge, at the expense of the Oromos (34 percent) and the Amhara (27 percent). Inside the EPRDF, in the military, the security services, state-owned enterprises and the university, residents from the northern region of Tigray claimed the most important posts. That domination came to an end when in March the EPRDF had to designate a new leader. New ethnic coalitions emerged during the internal election. The Amhara and Oromos lined up against the Tigrayans. After 27 years of a Tigray-dominated government, the balance of power had suddenly changed. “The first reason for the joy about Abiy Ahmed is that he is not a Tigrayan”, says Professor Abebaw Ayalew.

Such a remark smacks of narrow-minded tribalism, certainly in a state where ethnic tensions draw less deep dividing lines than in the African countries marked by colonialism. Yet it is precisely in Ethiopia that the past presents an obstacle to the modernization.

Immediately after his appointment Abiy Ahmed wanted to correct a historical issue. He chose the University of Addis Ababa to do this. To the delight of Professor Abebaw, the Prime Minister reintroduced independent history teaching. Ten years ago, Abebaw had to exchange his job at the university for a teaching position at the School of Fine Arts, because he had not kept to the official version of history. “The Ethiopian policy is always based on the past,” he argues.

The EPRDF sees Ethiopian history in terms of waves of imperial settlement, in which smaller or marginal ethnic groups came under the subjugation of the big ethnic blocks. That version bans the narrative emphasizing non-violent unification via the assimilation of Ethiopia’s different population groups- exactly what Abiy Ahmed is preaching. According to the EPRDF, Ethiopia lacked unity- in 1995 it formalized that division by creating a federation of ethnic regions. “The previous regimes abused history in their divide and rule politics,” Abebaw concludes.

Abiy Ahmed’s background matters in a country where over the centuries Christianity and state have become closely intertwined, and where emperors traditionally alternated between Tigray and Amhara. The Prime Minister is Oromo, Protestant and was only a child when in 1974 Scientific Marxism became fashionable. In the past, an Ethiopian Prime Minister would cite “democratic centralism” and “anti-peace and anti-democratic forces” when speaking to his people. Abiy Ahmed, in contrast, can be understood by everyone. “His language is clear and simple”, says Solomon Gedamu, the owner of Bole Michael’s grocery store. “He does not babble Leninist rhetoric. If you can speak as beautifully as our Prime Minister, you’ll convince people”.

Abiy Ahmed is the reconciler, the man of the people, the peacemaker, the man who revives a sense of pride, dating back to the empire. He emphasizes unity and gets everyone on board for his new dawn policies. He walked hand in hand through the streets of the capital Asmara with the until recently reviled Eritrean president Issayas. In America, visiting the one-million strong Ethiopian diasporas, he kissed children on the forehead and made many elderly people laugh out loud. Rebel movements sign peace deals with his government, reviled political opponents return from exile and quarrelling leaders of the Orthodox Church are reconciled.

None of this is risk-free. When on a drizzly Saturday in June hundreds of thousands of people went spontaneously to the central Meskel square of Addis Ababa to hear Abiy Ahmed speak, a grenade exploded at the lectern. After this failed attack on the Prime Minister, the body of Semegnew Bekele, project manager of the Renaissance Dam, the country’s national pride, was found in the same square a few weeks later. The government calls is suicide but the rumours persist that it was murder with the aim of preventing revelations of corruption with the project. This mega dam in the Nile symbolizes the great leap forward that Ethiopia is making, as ten percent annual growth takes if from poverty to a leading African nation. But it also symbolises the not fulfilled promise to finish the project last year. The question remains whether the Tigrayan clique will fight back to regain it’s former influence.

The honeymoon will soon be over. The country is experiencing huge turbulence and the emotions have not cooled down yet. In Ethiopia’s east and south, hundreds of thousands have been displaced. The rulers in Ethiopia’s ethnically defined regions have turned inward, encouraging violence against minorities. The biggest problem for Abiy Ahmed remains the past. He is heir to a dictatorial and ethnicity-built EPRDF. Is he going to kick the party that produced him? According to many activists, Ethiopia can not democratize with the EPRDF at the helm.

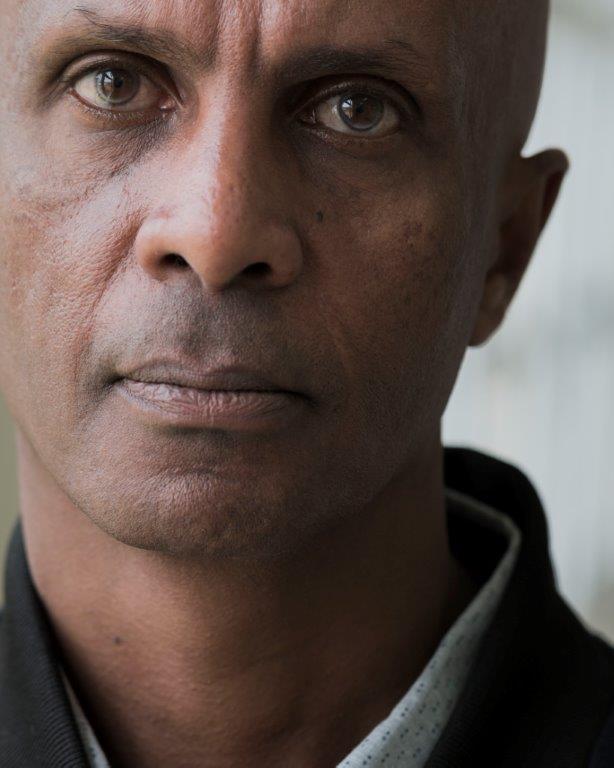

Eskinder Nega (48) was considered the most famous political prisoner of the dictatorship. Nine times the journalist went behind the bars, the last time in 2011 on charges of terrorism. In 2005 they picked him up for high treason with his wife Serkalem Fasil. He heard about her pregnancy in prison, where she delivered. Mother and child left for America after their release, she lives there now with their eleven-year-old son Nafkot. Since his release earlier this year Eskinder has hardly seen him. Unfortunately, that did not change during a recent visit to America. “Now that I have become a kind of a legend, I had to give interviews everywhere”, he says, “there was no time left for Nafkot. Journalism is my first love after all”.

Journalism in Ethiopia meant activism. Eskinder still has that fiery urge. In a small office in Addis Abeba he is preparing to produce a newspaper. He owes his release to Abiy Ahmed but his initial enthusiasm for the new Prime Minister has cooled. He wonders if the EPRDF will ever tolerate fair and free elections. “Abiy Ahmed should have formed a transitional government with all political forces included. He wants to polish the image of the EPRDF but won’t take the risk of losing in elections. It looks like a cosmetic change”. Zimbabwe’s recent events come to mind: a radical change at the top while much remains the same. “Abiy Ahmed is a celebrity as well as leader of an authoritarian party. That is dangerous”.

Carried forward on a tsunami of popularity, Abiy Ahmed cannot currently put a foot wrong with most Ethiopians. An Ethiopian leader has never been so popular. That is also his weakness. He is a one-man show, and if he falls away, civil war may break out. “If he dies, we all die,” predicts Solomon Gedamu, the owner of the grocery store in Bole Michael.

Photo’s: Support rally in Addis Abeba for Abiy Ahmed. And Eskinder Nega. All photo’s by Petterik Wiggers.

This article first appeared in NRC Handelsblad on 1-9-2018