Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Abdul (35 years old) can no longer sit still. He was a fighter once in one of the most brutal terrorist groups in the world. “Al-Shabaab messed up my life. My head, my heart, my chances. Everything.”

Abdul, who for safety reasons changed his name, constantly fiddles with his breast pocket. Every warrior from the Somali terrorist group keeps a grenade there to blow himself up in case of capture. “I always feared getting stuck behind a branch and accidentally blowing myself up.”

Abdul is Kenyan and was recruited in the Majengo slum of the Kenyan capital Nairobi by al-Shabaab in 2011 to fight in Somalia. “I wanted employment and the recruiter promised me a job as a driver.” Hundreds of Kenyans have been traveling to Somalia in recent years, from the Kenyan coastal strip and from the ghettos in Nairobi.

About a quarter of the Kenyan population is Muslim and lives mainly on the coast and in the poor lowlands that extend to the border with Somalia. Al-Shabaab controls territory in Central and Southern Somalia and set up a network of cells in Kenya. The terror group recruits poor young people in Kenya and offers them a salary. When they die, their families receive $ 500 and the deceased awaits 72 virgins in heaven.

Terror attacks in Kenya

More and more often the group uses the Kenyan fighters in attacks in Kenya itself. In January this year, Al-Shabaab carried out an attack on the Dusit hotel complex in Nairobi, killing 21 people. Three of the five attackers were Kenyans. The group previously committed attacks on the luxury Westgate shopping centre in Nairobi in 2013 (more than 60 deaths), on the coastal town of Mpeketoni in 2014 (also more than 60 deaths) and in 2015 at a university in Garissa (148 deaths).

Omar Boga is a social worker who tries to combat radicalization in the village of Ukunda along the Kenyan coast. “You see these few huts there across the road? That is where the planner of the attack on Dusit lived,” he gestures. “The recruitment by Al-Shabaab continues. True, many Muslims do live in the coastal area, but religion is not the reason. Young people go to al-Shabaab to escape poverty. This is one of the poorest districts in Kenya and al-Shabaab is luring them with jobs.”

The Kenyan government grants amnesty to fellow countrymen who turn their back on the Somali terror group. Omar Boga estimates that at least three hundred have returned in the last four years. Of these al-Shabaab fighters returning from Somalia, 42 were killed by extrajudicial executions. “Sometimes it was revenge by al-Shabaab, but the bulk of the murders are the work of the Kenyan police,” he says. “Although there is an amnesty, the police often respond to anonymous tips from citizens about returned criminals. And then the policemen start shooting immediately. Young people are caught between two fires: the terrorists and the police.”

Hunted down after leaving al-Shabaab

Amina (30) got amnesty and yet she went into hiding in a village along the coast. For security reasons, she took a new name. In her mud house under coconut trees, she anxiously watches over the entrance. She stops talking when someone threatens to catch our words. “Nobody knows my past, only my husband,” she says. “Maybe people forgive my murders in Somalia, but not the crimes I committed in Kenya.” Before she left for Somalia, Amina was a notorious gangster along the coast, ‘a most wanted person’.

She’s from a broken family. When her parents divorced, Amina had sought a sugar daddy to pay her school fees. He married her, but turned out to be a criminal. “He forced me into the underworld. I raided banks with his gang, robbed white tourists, ambushed the police, and invaded houses of Arab traders.”

When the ground became too hot under their feet she fled in 2014 with her husband to Somalia. “The recruiter for al-Shabaab called Somalia ‘a free country without police’. I thought: well, that is a beautiful country. There I can finally love my husband without danger and live in a nice house.”

Amina had to convert Christian Kenyans to Islam in a women’s camp for the terror group. “Sometimes young girls would arrive who had been promised a job as sex workers by the recruiters. I then arranged for their conversion to Islam.”

She snaps her fingers, the sound of a whip. And if that method didn’t work? She strokes her throat. Death by decapitation. “It was them or me.”

Amina spent four years with al-Shabaab. Until one day her husband did not return from the front. “Then warriors began to force me to sleep with them. During an attack on our camp in Somalia by the Kenyan army, I therefore ran and surrendered to the Kenyans.”

Amina sometimes thinks about the sparse good times with al-Shabaab. “The comradeship after a military victory, sharing your faith, freedom, yes, sometimes there were moments of happiness,” she says.

At the bottom of the pecking order

Al-Shabaab is so brutal that the late Osama bin Laden, leader of al-Shabaabs al-Qaeda ally, called in 2010 on the group to “act with more sympathy against the population.” “Every male fighter was assigned a wife,” says Abdul. “When leaving for the battlefield, my wife used to say goodbye to me with the remark: ‘I hope you never come back’. She hoped that I would die for the jihad.”

Within the group, not everyone is equal. “They called us black Kenyans adhon, a Christian, a slave,” says Abdul. “In the pecking order, the Somalis are at the top, then the Arabs, and we are at the very bottom of the ladder.”

Rape, stoning and decapitation were common. Not every warrior was allowed to do beheadings. “Only the emir had the right to do so if he had a special sharp sword. After the decapitation we had to play football with the head. To get rid of our fears.”

Abdul surrendered to the Kenyan intervention force in Somalia in 2016. He is still plagued by the spectres. “Radicalization means suppression of your human feelings. Every day I see those rolling heads. To become human again, to be able to deradicalize, you need a lot of strength.”

He looks around shyly. The veins knock at his temples, he covers his head with both hands as if he wants to prevent it from exploding. The fear never stops.

One afternoon Abdul was in a barber’s shop in a slum of Nairobi when a boy came in and shot him in the neck. However, it turned out to be a grazing shot and Abdul survived the revenge by the terror group. But in the evening, his alleged death, “the death of a deserter,” was just as well celebrated in the same neighbourhood mosque that had recruited him for the terror group a few years earlier.

This article was first published in NRC Handelsblad on 25-2-2019

The research was done with the assistance of Robert Ochola

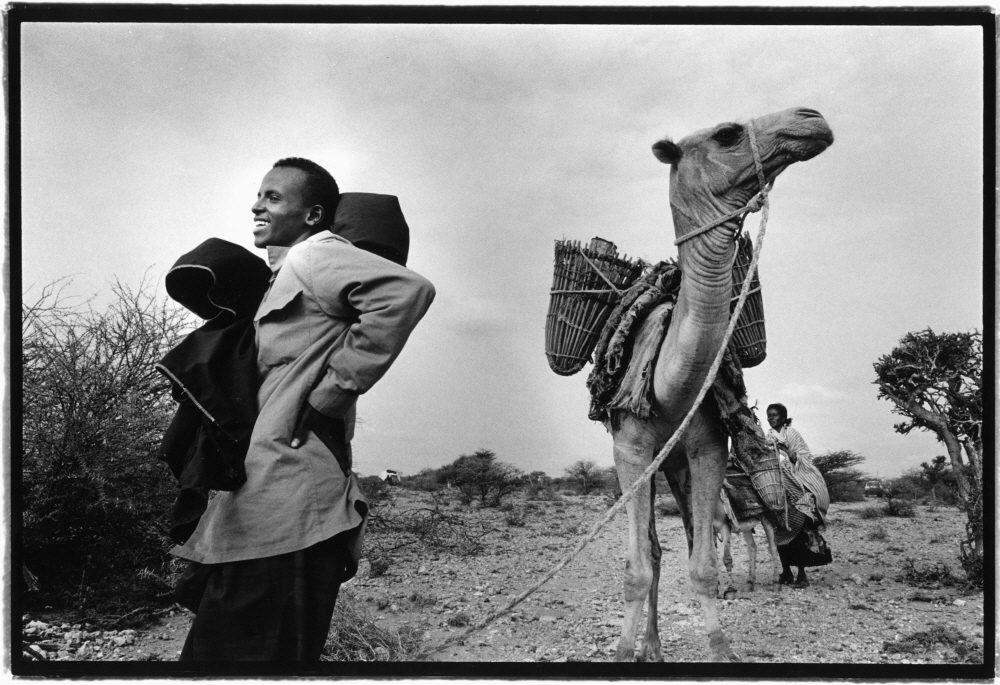

Photo’s by Petterik Wiggers