Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

All pictures by Joost Bastmeijer

At the end of the day , beaming with confidence Salome Nzyoka walks into a nursery in Wote to pick up her son. “I have been empowered”, the young woman says. As a member of the people’s committee, she oversaw the creation of this childcare center.

Since the introduction of a new constitution in 2010 citizens in the county of Makueni have been involved in new development projects. In this case it is a day-care centre, but it could also have been a mango processing factory or a dam. The secret of success? Using the money for development in a transparent, non-corrupt and democratic way. It is so simple but at the same time for Kenya it is a remarkable political renewal, led by 65-year-old governor Kivutha Kibwana. “If Kenya ever gets a national leader like we have here in Makueni, then things will work out for Kenya”, Salome Nzyoka says.

Kibwana shows himself to be a modest man, although his reputation is rising rapidly. The little man with a receding hairline and dressed in a dull grey suit does not easily attract attention, because he does not move around in a column of expensive cars and is not surrounded by advisers with a lot of bling bling, the usual gear of the Kenyan political class. His county of Makueni was recently mentioned in a research of all the 47 Kenyan counties as the least corrupt. His success is starting to stand out, at home and abroad. He is now mentioned in Kenya as a possible presidential candidate by those who pursue a non-tribal, transparent social-democratic model, ideals that the advocates of independence also nourished sixty years ago. But success provokes annoyance with corrupt politicians. “I make many enemies in the political elite and among civil servants who usually steal money from development projects”, Kibwana says. But the million inhabitants of Makueni enthusiastically support him.

A Kenyan easily becomes discouraged and cynical with politics. Because he lives in a bandit economy where, according to some estimates, half of the national budget “disappears” due to corruption and other mismanagement. “There are nevertheless opportunities for development. We provide the proof”, argues Kibawana. “Against the tradition of Kenyan politics, we are establishing a people’s government in our county. We managed to build a clinic for a third of the current price in Kenya. In this way we break up the patronage system. That means a revolution for Africa.”

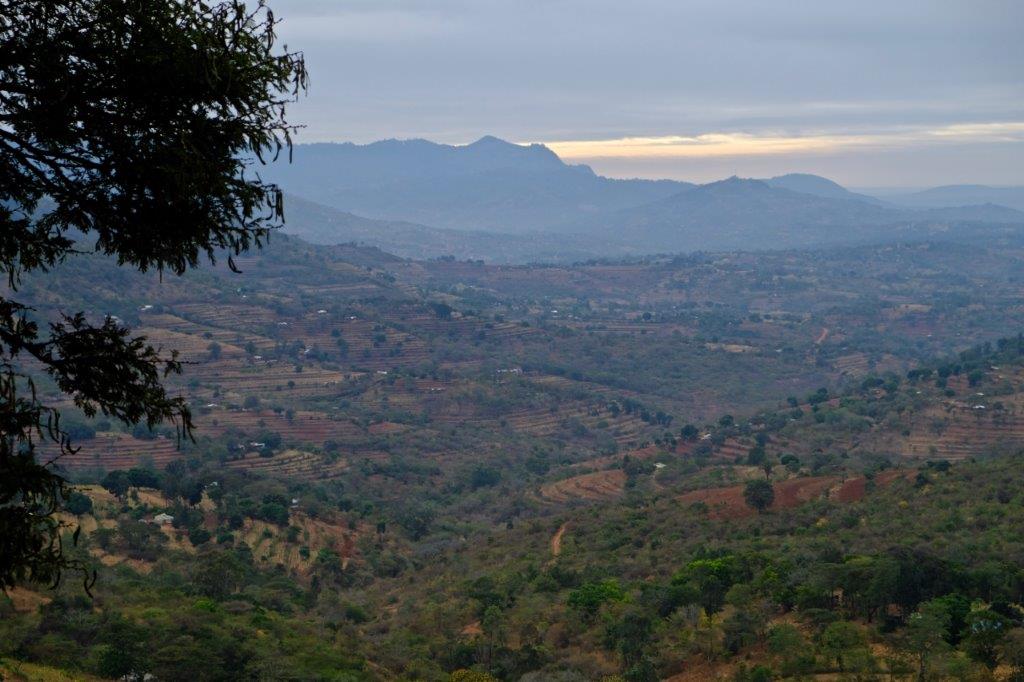

A three-hour drive from the national capital Nairobi on roads meandering between dry eroded hills and along dangerous gorges lies Wote, the administrative center of Makueni. It is one of the many counties in Kenya which were created in 2010. Kenya was then at a dangerous crossroads in its history after large-scale election violence two years earlier which pushed the nation to the brink of the abyss. A new dispensation was needed to prevent more civil strife.

A new constitution was adopted in 2010 after months of discussions and tug of war at meetings with citizens, politicians and experts, followed by a referendum. One of the prominent experts at these meetings was the then human rights activist Kivutha Kibwana. To bring politics closer to the citizen, state power was decentralized. But of course, that did not bring an end to the robbery of the nation’s wealth by an elite. Five years later, the former chief justice Willy Mutunga called the country in an interview with me “a bandit economy” with Al Capone’s in the lead. Auditor general Edward Ouko calculated how billions of euros were systematically “eaten”. Kenya’s status as one of Africa’s most corrupt nations remained unaffected.

Corruption-free and population-led development can be a matter of life or death for ordinary men and women. Take the recently completed maternity clinic in Wote. In the people’s meetings of villages, the residents raised two main grievances: health and water. On their recommendation, the local government built a fully-fledged maternity clinic for the same price as a pedestrian fly-over in Nairobi. Today in Makueni, twice as many women as before give birth in clinics instead of under unsanitary conditions at home.

An hour’s drive from Wote in the dusty countryside, the people’s committee meets to oversee the construction and maintenance of a water dam. “A long time ago we used to blow a cow horn when opening a popular gathering. Ordinary people had a voice then. After independence in 1963 that has not been the case anymore. Until Kibwana became our governor”, the old man Jonas Vuva tells me. As early as 1956 the residents asked for a dam in this dry land, but only after decentralization did their wish come true. “We had to walk half a day each day to get water. Now we have so much time for other work”, says Vuva enthusiastically. The committee supervised all stages of implementation. The contractor was always checked upon. Only after the residents were satisfied did he get paid. “Under Kibwana we no longer allow a bribe in Makueni”, Vuva laughs triumphantly.

Harrison Mutie is 38 years old and vice-speaker of the parliament of Makueni. Generally, people over the age of fifty dominate Kenyan politics, but in Makueni it is the younger generation’s turn. Kibwana focuses on youth, most of its employees are around thirty years old. “The politics in our county are not about how much you own, but how much you know. It is all very differently than during the time of my parents and grandparents”, he explains enthusiastically. “Decentralization brought democracy and public participation”.

The decision-making process proceeds along like a pyramid, but from the bottom up. Three times a year residents at the level of a cluster of houses make proposals for development projects, after which the proposal goes further up the pyramid to a collection of villages, up to the state parliament. That decision-making process is completely the opposite of how it was before decentralization. At that time, the Member of Parliament at national level in Nairobi proposed a project on behalf of the region and skimmed off a part for himself. He would only show up in his constituency around elections. “A member of parliament used to go to popular meetings with a lot of fanfare and in a column of cars, while we go on foot or by public transport”, Mutie explains.

The people-centered approach in Makueni provokes resistance, from contractors who must do without bribes and from corrupt politicians. Douglas Mbilu is speaker of the local parliament. He was hit by a bullet that was destined for Kibwana. “In Makueni we are radically changing the political dynamics. Ministers and members of parliament at national level oppose this. ‘Let’s stop Kibwana before the ordinary Kenyans realize that they have power’, our opponents warn us”.

Kibwana’s also experienced opposition in the local parliament during his first term as governor. “The local members of the county assembly claimed a large part of Makueni’s budget for their own well-being”, narrates Mbilu. “When Kibwana refused, they tried to dismiss him. When that failed, one day in 2014, a murder attack on him took place in parliament. I walked in front of him and caught the bullet”. And with a triumphant expression on his face: “All local MPs who demanded his resignation were voted out by the voters in the 2017 elections.”

Kibwana has remained the simply dressed former activist and remains an accessible politician. As his heroes he cites the Ghanaian Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972), who fought for the independence of Africa. And the Tanzanian Julius Nyerere (1922-1999), who taught the continent to rely on its own strengths. “These two made history in Africa. We in Makueni will make history too, if we use the available resources for the people”, he says. “It is possible to combat the arrogance of power and slay the dragon of corruption”

This artile was first published in NRC Handelsblad on 21-8-2019

All pictures by Joost Bastemijer taken in Makueni.

1 Wote, 2 Kibwana, 3 on the way to Wote, 4/5/6 the dam people waited for since 1956, 7/8 Maternity in Wote, 9 Kibwana and his team