By Daniela Mohor, Stanley Jerôme and Nyaboga Kiage

Marckinson Pierre/Reuters

Kenyan police stand in line at the international airport in Port-au-Prince on 25 June 2024 after being deployed on a UN-approved mission to rein in Haiti’s rampant criminal gangs.

After months of delay, an international policing mission is finally under way to help Haiti wrest back control of the capital’s streets from gangs and pave the way towards the Caribbean nation’s first elections since 2016.

Approved by the UN back in October last year, the Kenyan-led Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission has met significant opposition: in Kenya, a judge ruled that it was unconstitutional; in the United States, which is largely bankrolling the deployment, Republicans demanded more transparency and clearer objectives; and in Haiti, many are wary of outside interference given troubled and abuse-ridden interventions in the past.

None of this ended up stopping a first contingent of a few hundred Kenyan police from landing in the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince, on 25 June. As they begin work, this in-depth briefing explores why they’re there, what they’ll be doing, and what the implications are for millions of Haitians trapped in one of the world’s most intractable humanitarian crises.

What is the situation in Haiti?

Since the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021, gang violence has soared to unprecedented levels and dramatically reduced humanitarian assistance just when it is most needed.

Ralph Tedy Erol/Reuters

A man rides his motorbike past a burning barricade during a protest against acting prime minister Ariel Henry’s government amid Haiti’s growing insecurity, on 1 March 2024.

The security situation deteriorated even further in February this year when gangs joined forces in a so-called Viv Ansanm (Living Together, in Kreyol) coalition to overthrow acting Prime Minister Ariel Henry, launching coordinated assaults on police stations, government buildings, and key infrastructure; and taking control of the international airport and the main seaport.

After weeks of lawless limbo, Henry was replaced in April by a transitional presidential council. Garry Conille, a former regional director of UNICEF, has been chosen as prime minister to lead the interim government through to elections expected by early 2026.

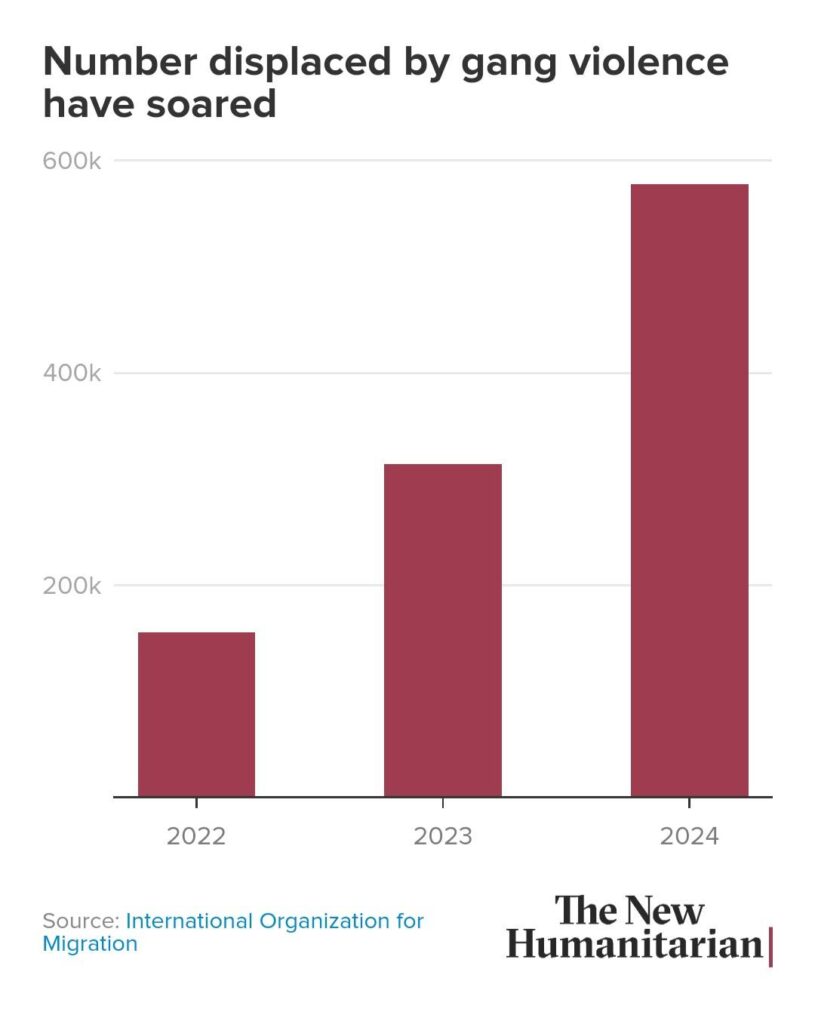

During the first three months of the year, 1,660 people were killed and 845 injured, a record high since the UN started monitoring human rights in Haiti in early 2022, and 53% more than the last three months of last year. Nearly 580,000 people are displaced, 215,000 more than in March.

The roots of Haiti’s problems date back to colonial times. Although the Caribbean nation became the world’s first Black republic in 1804, it was forced to pay billions to France in order to secure its freedom. That debt crippled Haiti economically and – combined with decades of dictatorships, natural disasters, political and environmental mismanagement, a long US military occupation, and a debilitating US trade embargo – contributed to its recent turmoil.

About half the population of 11.5 million now faces acute food insecurity. Kidnapping, rapes, and looting have become part of daily life, while the collapse of institutions makes it impossible to find protection, healthcare, and justice.

With gangs controlling all the main roads connecting Port-au-Prince to the rest of the country, bringing assistance to those in need is almost impossible. Gangs have also been extending their operations and areas of control to other parts of the country.

The toll on children is horrendous. A new UN report shows that in 2023, 128 children were killed and another 78 mutilated. Gangs used them in attacks against the Haitian National Police (PNH), tortured them, sexually abused them, and sometimes burned them alive. The UN estimates that 30-50% of armed group members are children.

Because many schools have been forced to close or because it is too dangerous to circulate in the streets, children are left with no education. Job opportunities are scarce too, often leaving young people no other choice than to join local gangs for survival.

What do we know about this new mission?

Kenya is leading the force and has committed to sending more than 1,000 police officers, who will be commanded by Senior Assistant Inspector General of Police Godfrey Otunge.

Other countries have pledged either personnel or logistic and financial support. In a statement released after the deployment, US President Joe Biden said he was “deeply grateful” to those nations, “including Benin, Jamaica, The Bahamas, Belize, Barbados, Antigua and Barbuda, Bangladesh, Algeria, Canada, France, Germany, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Spain.”

A US State Department spokesperson told The New Humanitarian that 400 Kenyans and approximately 250 Jamaican personnel have already been vetted, and the department “continue[s] to engage and vet personnel from other countries”.

The Kenyan authorities have said the police officers it has deployed belong to units that have fought al-Shabab jihadists at the Kenya-Somali border and are experienced in heavy combat.

The United States may not be officially leading the mission or sending troops, but it was the diplomatic driving force behind assembling it, and it appears to be responsible for financing, arming, and training it too. In the past month and a half, the US has flown dozens of planes into Port-au-Prince, bringing in equipment and civilian contractors to set up a new barracks and HQ for the mission near the international airport.

How is the mission being funded?

The estimated cost of the MSS is $600 million annually. A UN Trust Fund was created to receive donations from member countries to finance it.

In a November 2023 report, the Kenyan parliament stated that it required $241.4 million to prepare its 1,000 officers for the deployment, including: $1.5 million for training; $9.1 million for weapons, ammunition, and anti-riot equipment; and $157 million for administrative support. It also put as a condition that the resources needed by the MSS had to be made available prior to the deployment.

In February and March, to help to try and move things forward, Canada pledged an additional $60 million and the US $300 million to support the force, but a significant part of the US money was blocked by Republicans in Congress.

To finally get things moving, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken overrode Congress on 18 June and authorised the State Department to use $109 million to fund the MSS, in the hope that more donations from other countries would follow. Only $15 million of this amount had previously been cleared by Congress.

“The funding will support MSS requirements, including pre-deployment training, personnel reimbursements, equipment, provision of MSS Police Advisors, MEDEVAC capabilities, base refurbishments, and other logistical costs,” the US State Department spokesperson said.

So far, Canada has only deposited $8.7 million into the separate UN Trust Fund, the US $6 million, France $3.2 million, and Spain $3 million – for a total of $21 million.

What happens if the multinational force runs short on money remains unclear.

“Few of the countries that are offering forces would have the ability to self-fund for the operations that will be required,” Keith Mines, vice president for Latin America at the United States Institute of Peace, told The New Humanitarian. ”The funding is an issue”.

What is the mission’s mandate and how will it operate?

According to UN Security Council Resolution 2699, approved on 2 October 2023, the mandate of the MSS is to provide “operational support” to the PNH by “building its capacity through the planning and conduct of joint security operations” to counter gangs, to secure key infrastructure, and to “help ensure unhindered and safe access to humanitarian aid for the population assistance”.

The Kenyan and Haitian governments signed a Status of Force agreement on 21 June that hasn’t been made public but reportedly establishes the terms under which stationed troops can intervene and must conduct themselves. It is not clear what the terms are or if other nations contributing personnel will sign similar agreements.

Biden’s statement suggested more far-reaching aims: “Haiti’s future depends on the return to democratic governance. While these goals may not be accomplished overnight, this mission provides the best chance of achieving them.”

The mission was initially conceived as year-long with a review after nine months, but this was from the time of UN approval in October and no new timeline has been issued since.

Monica Juma, Kenya’s former foreign minister who now serves as national security adviser to President William Ruto, suggested the intervention could last longer, cautioning: “It is our hope that this will not become a permanent mission.”

The unusual nature of the force – UN-approved but not really a UN nor a peacekeeping mission – has some experts questioning who will really be in charge and how its procedures will work.

“This is uncharted territory,” William O’Neill, the UN-appointed independent expert on Human Rights for Haiti, told The New Humanitarian. “How will that force be able to operate in Haiti? How will they relate to the government? To civil society? What is their communication strategy? We have no answer to that right now. That’s a huge deal because it’s not going to be a police operation in isolation. The success of the MSS will depend on a lot of these other issues.”

Adding to concerns over clarity and transparency is the fact that neither the rules of engagement nor the mission’s concept of operations have been shared publicly.

The US State Department spokesperson said “the concept of operations (CONOPS) and operational approach of the MSS mission includes four phases: deployment, decisive operations, stabilisation, and transition”, but they refused to give more details “for operational security” reasons.

The UN resolution specified that the leadership of the MSS, in coordination with the Haitian government and participating member states, was required to inform the UN Security Council on the CONOPS, the rules of engagement, and the line of command prior to the deployment, but a UN source, who requested to speak anonymously, told The New Humanitarian that this hadn’t happened by 21 June.

“Apart from the Security Council resolution and last week’s agreement between Kenya and Haiti, there still is little documentation formalising the existence of the mission,” they said. “It is very worrisome that there is nothing clearly established yet.”

Is language going to be an issue?

Most Kenyans don’t speak French, let alone Haitian Kreyol, but opinion is divided on whether this will be a problem.

Lionel Lazarre, coordinator of the Haitian police union SYNAPOHA, said it wouldn’t be an issue because many PNH officers – like their Kenyan counterparts – speak English, and interpreters will be used as needed.

John Colem Morvan, a former Haitian policeman who now lives in Canada but maintains strong connections within the PNH, told The New Humanitarian that the plan was for Kenyan unit leaders to communicate by radio in English with the leaders of specialised Haitian units when operating together on the ground.

Kenyan police have also been taking French classes, while Morvan said the PNH’s high command had requested that almost all the Haitian brigades provide a list of policemen with knowledge of street combat who have a good level of English.

Others, however, worry how this will play out and wonder how the Kenyan police will communicate with the local population when they have to.

“The fact that Kenyans don’t speak French will cause many collateral damages,” said Mario Joseph, managing attorney of the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI) in Port-au-Prince. “Will interpreters be in the line of fire? How will they proceed to help foreign officers understand Haitians?”

Who has authority in Haiti?

The long-term power vacuum and continued political dysfunction of the past few months also raises concern.

After weeks of in-fighting between different factions on the transitional presidential council, Conille was appointed as transitional prime minister and formed a new government a few weeks ago.

But thus far, the Haitian authorities appear to have had little to no involvement in the deployment or in the planning around this crucial juncture of their country’s future.

Clarens Renois, general coordinator of the National Union for the Integrity and Reconciliation (UNIR) party – one of the coalitions with a seat on the transitional presidential council, explained that the political agreement that underpins the transition called for the creation of a National Council of Security and Defence (CNSD) that would develop a security strategy and work on the operational part of the MSS mission.

However, that council still doesn’t exist. “We should have a security council that works with the force’s command. But now nobody knows what will happen,” he said. “There is no interlocutor. This is a plan that was conceived without the Haitians.”

James Boyard, a Haitian professor, researcher, and security consultant, voiced similar unease. “My concern is that there is no framing mechanism for this force. There should be a security council that gives strategic orientation,” he said.

Unpopular police chief Frantz Elbé – accused of links to the gangs – was replaced by Rameau Normil days before the Kenyan deployment. Widely viewed as a positive step, it raised more doubts about a PNH leadership transition just as the mission began.

“My impression is that the security situation in Haiti has been left to deteriorate on purpose in order to force Haitians to accept this force without asking questions,” said Renois. “Now it has become indispensable, but the insecurity started three years ago.”

What does the deployment mean for aid groups?

Several aid organisations told The New Humanitarian they hadn’t been contacted by Haitian or Kenyan authorities to discuss the implications of the mission, although some UN agencies have had meetings with the PNH.

The mission could lead to clashes between the gangs and the new force. If so, the number of injured is likely to rise, right when medical supplies are scarce and dozens of hospitals and health centres in Port-au-Prince – and the surrounding Ouest department – have already been forced to close or scale back their operations due to gang violence.

“We are afraid of the consequences of this mission, of the fact that it could inevitably provoke more violence the population can’t escape from in a city that is so densely populated,” said Jean-Marc Biquet, who leads Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) operations in Haiti.

“We don’t want soldiers or police stationed in front of our centres,” Biquet added. “Weapons scare people, and we have already had patients not coming when there is a police car nearby because they fear being arrested, whether they are guilty of something or not.”

Anticipating a rise in violence, Mercy Corps has scaled up some of its safety protocols.

“We are updating our security and contingency plans, also our emergency preparedness plan, in case this brings more violence and there are increased needs of the population,” said Laurent Uwumuremyi, the organisation’s country director.

After Resolution 2699 was approved, both the Cadre de Liaison Inter-Organisations (CLIO), a local and international NGOs platform in Haiti, as well as the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) – which gathers together all the UN agencies and their local partners operating in Haiti – drafted a series of recommendations to safeguard their access and reinforce the distinction between the MSS and humanitarian actors.

These included the need to establish communications mechanisms to ensure that humanitarian actors are not perceived negatively, to initiate an effective dialogue between security actors and aid groups to preserve humanitarian space, and to comply with international humanitarian law, human rights law, and standards on the use of force, among other things.

The New Humanitarian could not confirm whether these recommendations had been transmitted to Haitian or Kenyan authorities.

UNICEF’s representative in Haiti, Bruno Maes, said the UN’s emergency aid body, OCHA, will soon appoint a senior liaison officer to lead civil-military coordination at a new intelligence monitoring centre created by the PNH ahead of the mission.

Up until now, aid groups have mostly been working on their own.

Ahead of the deployment, the International Committee of the Red Cross started reaching out to the PNH and the Kenyan police to convey its humanitarian concerns to the stakeholders. According to Marisela Silva Chau, head of the ICRC in Haiti, the PNH has been taking part in some meetings held by the HCT and a liaison cell created by the OCHA several months ago.

“It’s important to have a focal point in the [MSS] to ensure all the movements and all areas of work of the humanitarian actors working on the ground are known, to prevent any problem,” said Silva Chau.

The best-case scenario is that the presence of the force will eventually allow aid programmes to fully resume and Haitians to get the assistance they need.

Garry Calixte from CORE, a crisis response organisation with several programmes in Haiti, explained how the escalation of violence has prevented them from transferring the equipment needed from the capital to other regions where they have food security, climate, and water programmes.

“If the multinational force can restore order and provide more reliable and secure road access, I believe that it will be a relief for the millions of Haitians who are in difficult situations,” he said. “There are people in Haiti who live day by day. If they can’t go out to pursue their activities, they immediately become food insecure”.

How will the gangs react?

This is really the big unknown. Security experts point out that the delay to the mission has given gangs more time to prepare. Since news broke that the MSS was actually being deployed, some gangs have gone underground, while others have stepped up attacks, staged protests, or just continued to engage in violent acts and kidnappings.

Some gang members have spread songs with lyrics that threaten the force. Others have posted threatening messages on social media. In one video circulated on WhatsApp, a music group supporting Viv Ansanm sings a song that says. “We are not scared… Tell the foreigners to come, the Talibans are waiting for them.”

Haitian gangs could reportedly have bought a large inventory of Colombian weapons, increasing their firepower, and security experts on the ground say there is evidence of them coercing people not to leave certain neighbourhoods they control and/or trying to persuade displaced people to return to previously deserted areas.

Ralph Tedy Erol/Reuters

People escaping gang violence shelter at a sports arena in Port-au-Prince, on 1 September 2023.

In March and early April, gangs in two neighbourhoods – Carrefour-Feuilles and Croix-des-Bouquets – publicly urged civilians to return to their homes.

Pierre Espérance, executive director of the National Human Rights Defense Network in Haiti (RNDDH), said some gang members are now “panicking”, with the use of their own images on social media playing against them. Because they can now be recognised, Espérance said they can’t leave their territory without risking the wrath of the Bwa Kale vigilante movement that has killed many gang members in the past year.

“It will be very hard for gang leaders to move to other departments. So they will seclude themselves in their territory and try to use the population as protection,” he said.

In a worst-case scenario, the deployment of the MSS could simply drive gangs to move their operations into other areas, jeopardising the access that aid groups have managed to maintain outside the capital.

How will children be protected?

As many as one in two gang members are children, so the need to shield young people from violence – and imprisonment – is a priority: Save the Children, Plan International, and World Vision issued a statement warning of the risk of increased child casualties.

“An increasing number of children in Haiti have been driven to join armed groups due to hunger and desperation,” it said. “These children are victims of child rights violations, and must be treated as children, not as militias.”

“Our main concern is how to prevent more children from being forced to join armed groups… and how to provide them with the support necessary to safely disengage and reintegrate with their families and communities.”

To maximise children’s protection during the MSS mission, UNICEF sent a senior representative to Nairobi last December to advocate for pre-deployment training.

The agency has also been working on modules – inspired by some used in Mali – to train those involved in the MSS mission. The training will focus on international humanitarian law, the Paris Principles, and include information on Haiti’s national laws as well. It will also provide information on the procedure to follow when children are encountered on the field.

“Our main concern is how to prevent more children from being forced to join armed groups… and how to provide them with the support necessary to safely disengage and reintegrate with their families and communities,” Maes said.

An agreement signed last October binding Haitian authorities to take responsibility for the protection of children who joined gangs during security operations was a significant step forward, he added.

As part of its efforts to avoid casualties and abuses, UNICEF has also funded a reception and transit centre for teens who are captured or who defect from armed groups. Managed by the Haitian Institut du Bien-être social et de la recherche (IBESR), the centre already has a large team of social workers.

What about accountability for any abuses?

“We’ve worked with Kenya and other partners to integrate critically important accountability and oversight measures into the mission,” read Biden’s statement.

Biden didn’t say what these measures are, but Resolution 2699 stipulates the need to establish “robust compliance mechanisms to prevent, investigate, address and publicly report violations or abuses of human rights” and for the MSS to ensure “children and women’s protection”.

The long history of abuses related to foreign countries’ policies and interventions in Haiti makes this issue all the more sensitive.

During the 19-year US occupation that lasted until 1934, Haiti’s natural resources were exploited for the occupier’s benefit, and Haitian rebellions led to the killing of thousands. The following succession of US-backed dictatorships caused massive human rights violations, including arbitrary arrests, torture, enforced disappearances and political killings.

Later US involvement in foreign interventions further undermined Haiti’s stability, especially the 13-year UN “stabilisation” mission (MINUSTAH) that left a legacy of allegations of sexual abuse and exploitation, and a cholera epidemic that claimed more than 10,000 lives.

Meanwhile, concerns over the Kenyan police’s history of rights abuses has long loomed over the MSS. Deadly clashes between police and anti-finance bill protesters now shaking the East African country have only heightened those fears. According to news reports, the police opened fire on protesters who tried to breach the parliament in Nairobi, killing at least 13 and wounding dozens more.

“Kenyan police officers are known to abuse the rights of people and get away with that,” said Evans Ogada, one of the lawyers involved in trying to block the Kenyan deployment. “We do not expect anything different [in Haiti].”

Human rights activists have warned that neither the safeguards needed to prevent and address potential abuses, nor the structure to assist and compensate victims, seem to exist.

“We have seen nothing that would actually constrain the force in a meaningful way and that would ensure that accountability will be available to victims,” said Alexandra Filippova, senior staff attorney at the Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti (IJDH).

This article was first published by The New Humanitarian: