Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Felix Tshisekedi was declared the winner of another disputed election on Sunday the 31st of December with 73 perscent of the votes. His major rival Moise Katumbi got 18 percent. Accusations by opposition leaders of electoral fraud and political repression will likely cloud his second term as it did the first. His main rivals rejected the outcome before it was announced and called for a rerun.

Election in the Democratic Republic of Congo are normally a farce that reflects the chaos prevalent in the vast nation. The country, abundant in natural resources, has long been a target for foreign companies, neighboring countries, and as well as Congolese politicians, who all exploit its vulnerabilities for their own gain. In this environment, opportunistic elites engage in fierce competition during campaigns, showing little regard for the principles of democracy.

In 2019, Africa had witnessed one of the most shamelessly manipulated elections ever, as Félix Tshisekedi (60) was declared president despite receiving only 19 percent of the vote, compared to his rival’s 59 percent. In the recent elections held at the end of 2023, Fatshi, as the president is sometimes humorously referred to due to his weight, sought to establish legitimacy and distance himself from the perception of being a fraudulent leader.

The primary focal points of the campaigns revolved around poverty and safety. Despite a 6 to 9 percent growth in GDP over the past three years, primarily driven by higher commodity prices, the Congolese population found themselves burdened with increased expenses for food and transportation. Consequently, the number of individuals living in poverty escalated, with over half of the population surviving on a mere 2 euros per day, despite Congo’s abundance of minerals and lush resources akin to El Dorado. “We can no longer cope with those price increases,” complains radio maker Primo Nzela by telephone from the city of Kisangani. “That was the only reason people attended election rallies, in the hope of receiving 5,000 francs (1.60 euros) as an attendance fee, or a T-shirt. Tshisekedi failed to improve our lives and that is why we hope for a victory for opposition candidate Moïse Katumbi.”

Around 1.7 million voters residing in eastern Congo were unable to exercise their right to vote due to the presence of multiple armed groups vying for power and resources. Despite Tshisekedi’s promise five years ago to eradicate this armed chaos, it has escalated. Additionally, nearly half a million individuals have been forced to leave their homes in recent months, resulting in a total of seven million civilians displaced throughout the country, a global record. Tshisekedi’s opponents, including Moïse Katumbi (58) and Nobel Prize laureate Denis Mukwege (68), criticized his ineffective policies during their campaigns and vowed to implement stronger military measures.

Moise Katumbi

An electoral battle in the country of around a hundred million inhabitants is a competition between a few elite coalitions behind the candidates. Tshisekedi uses public money, his biggest rival Katumbi is a wealthy businessman from the southern, mineral-rich region of Katanga where he owns one of Africa’s most successful football clubs, Tout Puissant Mazembe, and where he proved to be a good manager as governor (2007-2015).

Richard Moncrieff, from the International Crisis Group (ICG) think tank, says “For the big politicians, fraud, manipulation, lies and oppression are part of their toolbox,” and he continues “But Congo is not a dictatorship, like neighboring Cameroon. Citizens exert some influence, either by voting or by organizing themselves in action groups. Citizen groups mobilized twenty thousand election observers to check for fraud, which says something about the pluralism in the country.” Around elections, every politician tries to prepare for a new role, preferably as close as possible to the upcoming winner, because prestige and money can be gained through that proximity. “Party alliances in Congo are temporary, politicians think about their future and bet on the winner,” says Moncrieff. .

In the 2018 elections during the tenure of outgoing President Joseph Kabila, a secret agreement was reached between Kabila and opposition candidate Martin Fayulu (67). Despite receiving the majority of votes, Fayulu was not prosecuted for his involvement in large-scale corruption, due to this agreement. The Electoral Commission, which was under Kabila’s influence, declared Tshisekedi as the winner. The Supreme Court, manipulated by Kabila, upheld this decision. Despite his party holding only fifty out of the five hundred seats in parliament, Tshisekedi managed to gain a significant majority within two years. He rewarded defecting MPs with new jeeps and appointed favorable judges to the Supreme Court and members of the Electoral Commission. Additionally, he frequently reshuffled his cabinet, following the footsteps of Kabila and previous presidents.

In his second term, Tshisekedi is expected to start few social projects again. In 2018 he promised free education, but the teachers were not paid. He will continue to capture state revenues and corruption in the mining sector to strengthen his position in the competition between the networks. Congo is experiencing a boom in the raw materials sector, such as copper, gold and coltan. “That’s where the big money lies,” says Moncrieff. “Tshisekedi’s associates, including his family, have aggressively entered Katanga’s mining sector.”

Green energy transition

Congo has large reserves of raw materials needed for a green energy transition in the world. Raw materials are both Congo’s blessing and curse. In the east they brought doom to the residents, with crimes against the population comparable to atrocities committed in the world’s worst war zones. The gynecologist Denis Mukwege comes from the area, who operates on women raped by militias in his clinic and received the Nobel Peace Prize for this in 2018. He is less known in Congo and lacks funds to campaign.

In an effort to calm tensions in the eastern region, Tshisekedi initiated a diplomatic approach in 2019 by establishing friendly relations with Uganda and Rwanda, two neighboring nations known for their historical involvement in eastern Congo. However, the amicable bond with President Paul Kagame of Rwanda proved to be short-lived, leading to an escalation of violence in recent months. Tshisekedi openly accuses Rwanda as the primary instigator and does not hold back his criticism, even drawing a comparison between Kagame and Hitler during an election rally.

Dozens of armed groups operate in the east, according to some estimates even more than a hundred, who finance themselves with the abundance of easily extracted raw materials, such as gold. The Rwanda-affiliated M23 plays a leading role in the range of rebellious groups. “The M23 is the best organised,” says a resident of the regional capital Goma who wishes to remain anonymous. “They occupy areas and install their own government. For the other groups, all citizens are targets, including in maternity hospitals.”

Currently, the primary concern revolves around whether the elections were perceived as fair, thereby granting Tshisekedi his initial sense of legitimacy.

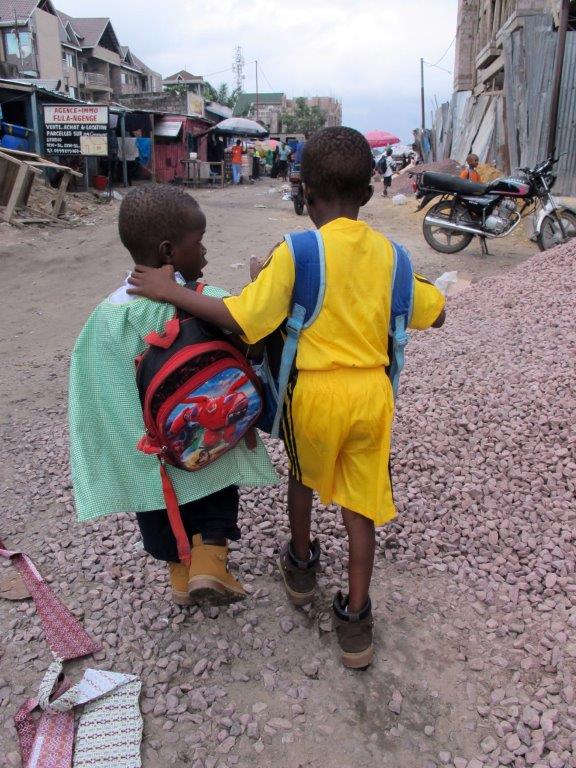

Photo’s(except the first one of Tshisekedi) by Johannes Dietrich