By Richard Dowden

Amentu, Ethiopia. The Rift Valley in Eastern Africa is our hole in the ground, where we all come from. Not far from here our earliest ancestors stopped hanging out in the trees and started to use their rear limbs to get around on. From here we began to migrate and multiply all over the world. Today a line of worn tarmac runs along the valley floor, fed by earth tracks through fields of stubble lying brown and empty after the harvest. Wriggling lines of green mark streams which lead to the Awash River. The east and west horizons are bordered with crazy grey mountains jagging into a light blue sky. Flashing like mirrors in the sun are the valley’s huge blue lakes and, in recent years, vast rigid squares of plastic sheeting have sprung up.

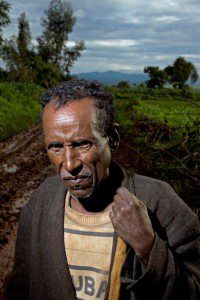

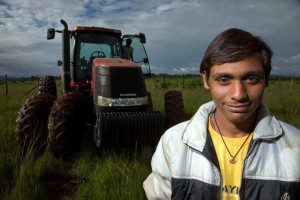

Two models of development sit cheek by jowl where mankind began to emerge some 3.6 million years ago. One model is struggling to grow out of subsistence farming. It is a step-by-step approach, communal, dependent on rain, prayers and a little aid and expertise from outside. The other model is flower farms, believed to be the largest in the world, they are driven by 21st century global capitalism, dependent on complex chains of production and transport, sophisticated financial systems and Europe’s demand for pretty summer blooms in winter. Turnover in 2008 was estimated at more than $100 million. One Dutch flower farm is an 800 hectare estate which employs 13,000 people locally. More than ten years ago the Ethiopian government begged western horticultural companies operating in Kenya to come and invest in Ethiopia. They gave them land and a free hand. Now the farms provide more than 50 percent of export earnings, more than $300 million, and employ thousands of people.

Seven years ago Ethiopia was exporting $12 million worth of flowers. But it is not as easy as it sounds. Flowers, fruit and vegetables are very vulnerable to delays of a few hours, so the process from picking, packing, driving to an airport, flying and delivery to European outlets has to be perfect. Having induced them to invest, the Ethiopian government is trying to force the flower farms to employ only Ethiopian firms to provide the packing and transport services the farms need. That, the flower farm owners argue, will take time. Nearby is a local cooperative of 94 farmers growing vegetables for consumption locally and for the towns. The people in the cooperative are Oromo – formerly transhumance cattle keepers who wandered with their herds on seasonal routes in search of grazing. This lifestyle, strongly disapproved of by successive Ethiopian governments, has changed to settled farming but the soil here is light and sandy – easily eroded by seasonal flooding.

A group of about 20 members gather under the shade of a huge thorn tree looking out across the flat valley to the lake and the mountains in the far distance. Birdsong is interspersed with cellphone rings and chimes. Most of the members have phones – though some are barefoot. They are very disciplined, putting up their hands up to speak. This narrative is taken from several voices among them. “The cooperative was set up in 1993 to make the poor and marginalised self sufficient. When we get extra money we rent more land and send our children to school. Investing in land is safe because we do not know what will come. Or we construct a better home or buy cattle. A house is an asset and from cattle you get money for milk.”

“We operate a savings and credit system and also a seed bank. Members get credit which they repay after the harvest. But in the last five years the Belge rains (short rains which should come in March) have failed. It was hard to repay. But we cannot complain.” Life is a struggle and the cooperative needs constant support from outside. It has to maintain tracks and paths so that their small two-wheeled carts pulled by mules and donkeys can carry bags of maize and boxes of tomatoes to roadside markets from where they will be bought by merchants to feed the towns. The savings and loans system needs top ups so the members can get credit, obtain better seeds for maize and onions from seed banks. “The basic co-operative law is that he who works gets the benefit. It is aimed at credit provision and asset building.

The problem is that repaying depends on the strength of the market. All the surplus comes to market at the same time. This year the price of a kilo of maize has swung from 40 cents (1.36p) to 10 birr (34p).” One problem is that the farmers get ripped off by the buyers from the towns. “We need to break the chain of brokers (the merchants who come to buy the produce). They hunt as a pack and decide the price among themselves. Onions are ok because you can store them, but with horticulture crops there is a problem with perishability so the time-frame for selling is short.” Another issue is that some smallholders now rent out land and employ workers and some members say this creates a problem because they have more capital and higher production so bring down the market price. All the farmers say the priority now is water. “We want to buy a water pump to irrigate the crops when the rains do not come.

There is a long term problem with rainfall. The short rains that are supposed to come in March have failed for the past five years.” Because all land in Ethiopia is state owned and controlled, the flower farm has been given the best of it. The farmers complain that it also takes water from the lake and chemicals from the flower farm are poisoning the lake – an allegation the flower farm owner fiercely denies. Not far away a women’s cooperative is also trying to turn a profit from farming, but in a different way. It started more than 20 years ago with a small loan.

Traditionally in this society the women did a lot of the hard farming work and the carrying; firewood, water, sacks of grain. I meet the women under a large tree in a fenced field with a shed in one corner. I am given a small stool but the woman sit, their legs stretched out straight on the ground. They are of different ages but all have wrinkled faces and thin, wiry bodies. “We started to discuss common issues and invest in livestock; sheep, goats and cows. We also started to learn to read and write. Our aim is to give training and make a profit.” “Our life is not comparable with the old days. It is the difference between earth and sky. It is not comparable. We used to grind grain with stones. That made your hands rough and takes a long time. Women could not meet like this but now we are free to come. There was polygamy. Some men had three or four wives and the oldest one gets abandoned and has to go on working. Female genital mutilation was common but now it is almost stopped. There is still dominance of men but polygamy is rare now.” Before, their children had to stay at home or come back to help with the harvest, but now they go to school and are free to go and find a job.

The women are clearly better off, more in control and happier than they were in the past. Their current concern is the cost and maintenance of the grinding machine and the cost of fuel. They want an electric one which will cost 5000 birr, but they have worked out that it will be cheaper to run. They also want a better seed bank. The biggest problem which affects everyone is that the water table is going down. Too many people are using it. They do not mention the flower farms. The women have also discovered that if they store grain in their shed and wait until the price rises, they can grind it and make a very good profit. They can also charge others for storage and grinding. Last year they made 1000 birr on an investment of 3000.

It sounds like they are beginning to act like the grain traders their husbands complain about. How will the 21st century flower farm coexist side by side with agriculture that is done by hand and is dependent on rain? The two models of development exist side by side but seem to have little contact with each other. They will increasingly compete for water and land though there is still a huge labour pool to draw on. At the moment most of the farmers on the cooperative seem to be better off than the workers on the flower farms – though the workers can use the flower farm hospital for free. But in the longer term will the flower farms take over the land and water, absorb all the labour and reduce the local population to wage labourers? Or will the flower farms engage with the cooperative, help upgrade its produce and buy it? *** At last some good news from South Africa. According to the new Rapid Mortality Surveillance Report by the Medical Research Council, life expectancy rose from 56.5 in 2009 to 60 in 2011, already ahead of the 2014 target of 58.5. And the Under Five Mortality Rate has fallen from 56 per 1000 live births in 2009 to 42 in 2011 – again ahead of the 2014 target of 50. Almost all of this is believed to be down to the provision of anti-retroviral drugs.

Richard Dowden is Director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa; altered states, ordinary miracles.