A journalist & academic with a Ph.D. in applied linguistics. He works in various fields; teaching, translation, editing, writing for digital newspapers, and human rights defense.

Ever since Hanan, (pseudonym) a Sudanese mother of two school-age children and a survivor of sexual violence experienced the incident in Khartoum the capital, she escaped and ended up in a refugee camp, her children have started displaying a lack of appreciation and respect towards her. “Once my daughter was fighting her brother, she held down his head, when I told her to stop, she said to me: ‘when you refused to lay down, those people also did like this to you.” She told in a sad voice.

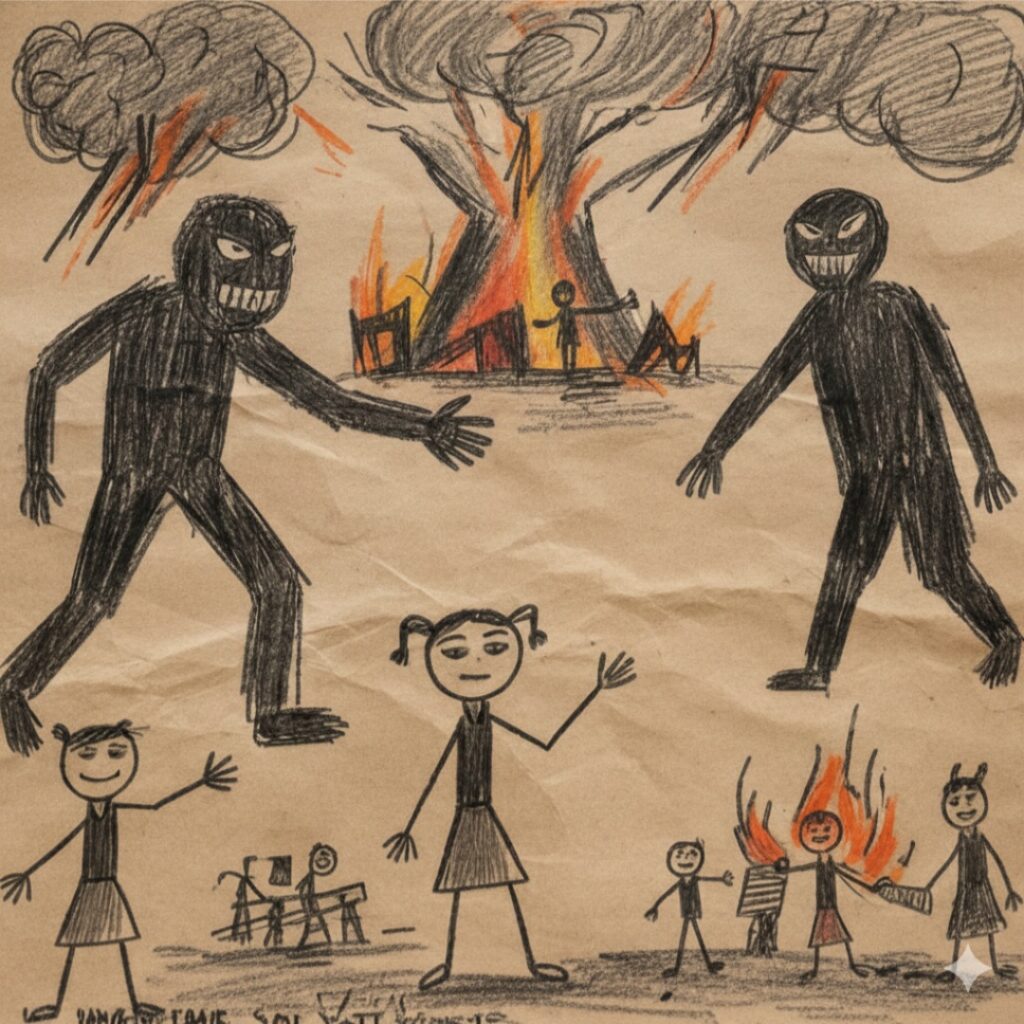

This picture is AI generated

The impact of the war on children is immense. It has left severe and enduring physical, emotional and psychological impacts on children. Over 90% of the country’s 19 million school-age children have been forced out of formal education. Among the displaced, children are the largest. The conflict has subjected children to horrifying violations, including forced recruitment, sexual abuse, and kidnapping. Children are struggling with hunger, lack of safe water, and they missed vaccinations.

Several Sudanese families and their children are now refugees in neighboring countries, enduring life in makeshift camps. They are exposed, sheltered only by tents crudely constructed of straw and scraps, which offer minimal protection against the harsh sun and the heavy rains. However, they are finally free from the deadly violence they faced back home, where safety was nonexistent. “They raped us in front of our children”, Hanan, said in a weak tone of voice.

The abusive behavior of Hanan’s children, particularly the daughter’s statement, is not mere indiscipline, but a direct result of the violence and trauma that affected Hanan. Since she was physically and psychologically harmed, her trauma is now visibly impacting her children’s behavior and the entire family’s well-being.

Hanan added: “my children are out of school now. I hope that they won’t display similar behaviours when they go back to school. I don’t want them to be affected by the incident in their learning.”

This picture is AI generated

These post-traumatic experiences are stark examples highlighting the widespread harm the ongoing conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which erupted in April 2023, has inflicted on the children of Sudan. It has subjected the people to extreme violence, violations, and trauma. The UN now recognizes this as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Tens of thousands have been killed, and 12.4 million people have been displaced including over 3.3 million refugees leaving millions more without homes or businesses.

From my perspective as a University Assistant Professor in teacher training college, I would argue that preservice teachers in the teacher training colleges in Sudan must be trained to recognize the symptoms of trauma and methods of solutions in schools post war. This requires an immediate response: a trauma-informed teaching approach which helps teachers understand the impacts of trauma and suggests proactive strategies to position the school itself as a predictable milieu for healing and growth. Trauma is an adverse experience that compromises an individual’s sense of being safe in relationships and in the world around them; and can significantly inhibit both self-regulatory and relational capacities required for successful learning.

While the war is not over when it has ended, it continues in the heads of people, leading to anti-social behaviour, like what Hanan has experienced with her children. However, there must be measures to be taken to address the post war circumstances in education. The new approach must be fully integrated into all curricula and teacher-training programs for different educational settings: primary, intermediate and secondary to address widespread trauma in Sudan.

In normal situations in Sudan, preservice teachers in colleges of education undergo a 4 to 5-year bachelor’s program that integrates theory, subject matter expertise, and practical pedagogy. Before graduation, they complete a supervised teaching practice placement in schools, guided by their university professors.

Given the current unprecedented situations of disruptive learning and trauma, the focus must shift to address the unique psychological and emotional needs of the students. This requires integrating the trauma-informed teaching into the program, which fundamentally changes an educator’s perspective: instead of asking, “What’s wrong with this student?” We must train preservice teachers to ask, “What has happened to this student, and how can my knowledge and awareness help to recognize the signs of trauma and implement strategies that create a safe, supportive, and predictable learning environment to foster healing and resilience, not re-traumatization.

However, the response is significantly hampered by three main issues: instability and resource scarcity within teacher training colleges; widespread infrastructure destruction. Several educational facilities are damaged or used as IDP shelters, thus preventing the creation of safe learning spaces. Educational institutions rely on online operation due to ongoing conflict. This reliance on online delivery limits the colleges’ ability to provide the practical, in-person supervision needed for preservice teachers to develop essential sensitive skills, like trauma-informed practice.

While reforming the education system with a trauma-informed approach is essential, it is only one part of a much larger, necessary effort. Sustainable healing and social cohesion require genuine, comprehensive national peace and reconciliation processes. Sudan has been in wars for most of its existence. In 2003 the world witnessed massive violations against Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa communities, resulting in the UN Security Council referring the situation in Darfur to the International Criminal Court in March 2005. The very year a Comprehensive Peace Agreement ended the long war in the South, though that region’s deep wounds led to its separation in 2011. Decades of popular anger and repression culminated in the December 2018 Revolution, which overthrew President Omar al-Bashir in April 2019 and brought short hope for democracy. But this transition was tragically cut short by the October 2021 coup by the SAF and RSF, plunging the country into the current conflict. Throughout this long history of war and violence, marked by ethnic killings and mass displacement, Sudan’s social fabric has been shattered, creating deep-seated distrust and a loss of national identity where people rely on ethnic networks instead of formal systems.

Because these crises have caused profound psychological trauma, national recovery requires more than immediate response in the education level: the international community must exert its efforts to end the current conflict to secure children’s safety and education. The government and global partners must collaborate on peace-building and simultaneously rebuild the entire educational system from curricula to teacher training with a trauma-informed approach that requires funding and research to be carried out by the teacher training colleges. Global partners on mental health can also help by providing essential mental health support and counseling for Sudanese refugees especially women and children who constitute the vast majority affected by traumas.

This picture is AI generated