Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

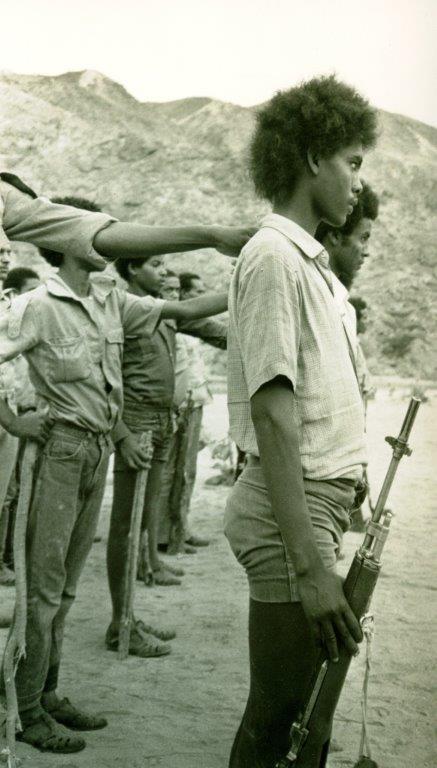

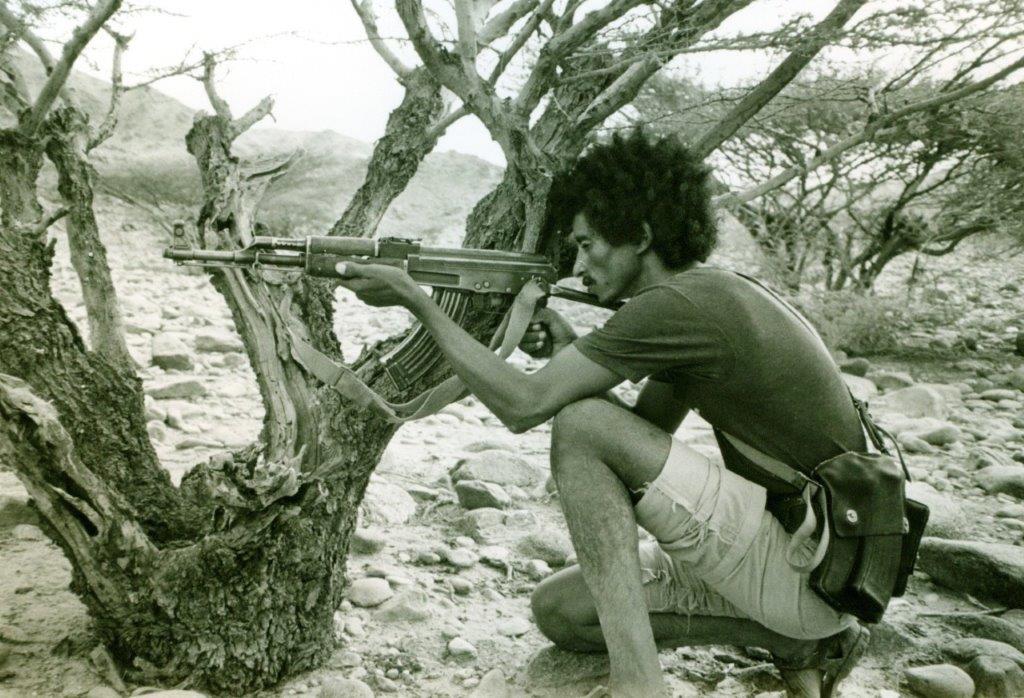

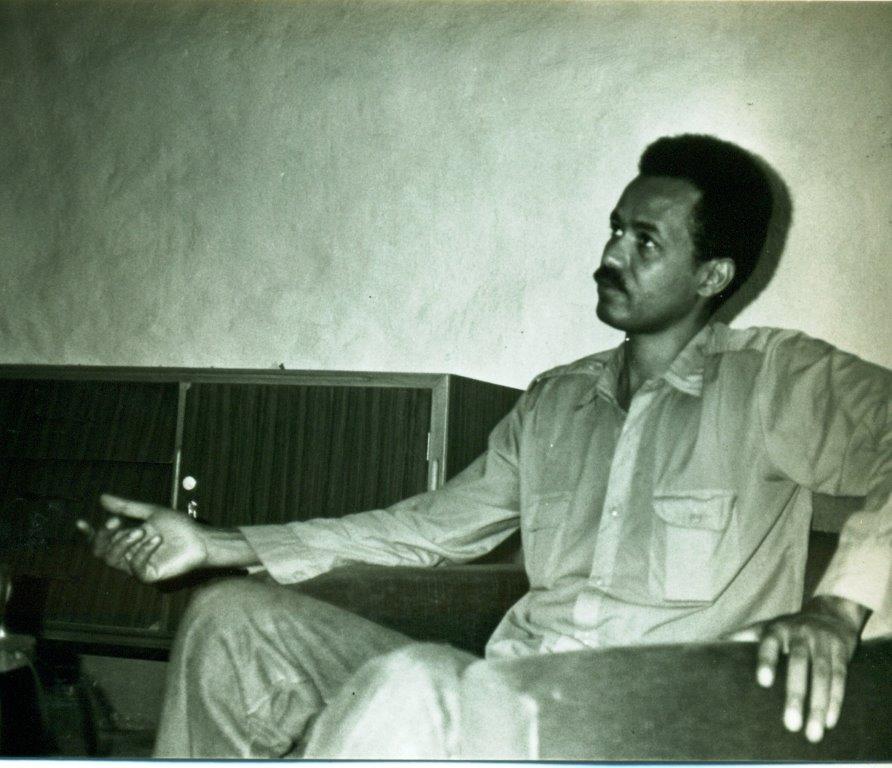

| ‘Never get on your knees.’ With that battle cry, the Eritreans took on the Ethiopian army, the largest army in Africa, for thirty years until 1991. “We have moral and physical courage,” said Isaias Afewerki (78), then rebel leader and now president of Eritrea for more than thirty years. “We have created our own political culture.” Thirty years after its independence, Eritrea is a nation that still lives this history of the liberation struggle. The Eritrean regime is angry with the world but pleased with itself. In this small but militaristic state along the Red Sea, every opposition has been suppressed, every dissident voice banished. Not only is it one of the poorest countries in the world, it is also a gigantic prison from which legions of young people are trying to escape, with perhaps a tenth of the population having fled, according to Human Rights Watch. A party of Dutch Eritreans in Opera Zalencentrum in The Hague got out of hand on Saturday the 17th of February 25, 2024 when aggressive opponents of President Isaias stirred up. They pelted the police with stones, police cars went up in flames and the meeting center was damaged. Violent incidents involving opponents of the dictatorial regime regularly occur in Germany, the United States, Australia and Israel, among others. The Eritrean diaspora has always had a role in the domestic politics of her country. During the liberation struggle, they provided significant financial support to Isaias’s Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF). “Of course we donate part of our income to the resistance fighters of the EPLF. With full conviction,” Eritrean exiles told me in 1986 during a visit to the front in Eritrea. They had come from Europe to express solidarity with their visit to the trenches. Eritrea under Isaias Afewerki is now known as the most closed country on the continent, the once solid unity is crumbling The brave freedom fighters with afro hairstyles, dressed in tight shorts, commanded admiration. Few regimes in Africa created so much hope, only to later be so deeply disappointed. The EPLF, which now forms the government, pursues a militaristic policy; Young people must serve for an unlimited period of time and older people can be called up for military service until after the age of fifty. And the voluntary contributions of the exiles at the time have become an enforced diaspora tax. Eritrea under Isaias Afewerki is now known as the continent’s most closed country, its once solid unity crumbling to feuding Eritreans at home and abroad.  Wonderful society At that time they lived in a wonderful society. Money did not exist during the liberation struggle, everyone worked without a salary, everything was shared, driven by a rigid conviction and absolute solidarity. Under the leadership of the EPLF, the Eritreans created a state in the making. They carved hundreds of kilometers of roads out of the mountains, built schools, built dams, undertook agricultural projects and reforested. In underground factories in a rugged landscape of sand and stones they produced medicines, plastic sandals, sanitary towels, cutlery and spare parts for cars. After the liberation struggle, Isaias thought he could continue that mentality. “Manpower is always available,” the president proclaimed. With that confidence in its own strength, Eritrea sent foreign aid workers out of the country in 1996 and forced young people to work in development projects. In this way, just like the veterans at the time, they would get to know the values of the barren bush. A former EPLF soldier once told me about that unique hardiness: “Every fighter had the same feeling: ‘I sacrifice myself for my country.’ When your friends died, you actually fought harder. The crackle of the bullets sounded like music, you wanted to keep going until the trigger hurt your finger. We had a spirit of Spartans.” But Spartans belong to war, not to peace and democracy.  Military cycle One war led to another in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea plays a leading role in that military cycle. Just as younger Eritreans began to turn away from the martial discipline of the past, Isaias forced this generation back to the front line. From 1998 to 2000, Ethiopia and Eritrea fought a large-scale border war that left hundreds of thousands dead. Since then, Eritrea has intervened in several wars in the region, such as the one in the Ethiopian state of Tigray in recent years. More than half a million people died. Eritrean soldiers were notable for gross war crimes fueled by anti-Tigray indoctrination. The government has recruited at least ten percent of the population for the armed forces. Isaias uses the cultivated military discipline to eliminate any form of opposition. On a dark September day in 2011, all hope for a democratic Eritrea was lost overnight. After a group of fifteen ruling party members demanded more democracy and openness, Isaias jailed the dissidents, including ministers and parliamentarians. Students and journalists were rounded up and sent to labor camps. The arrogance of power was now complete in the capital Asmara. The methodology of the liberation struggle continued, but the goal is now oppression. Young people are fleeing their country in hordes to avoid military service. The diaspora tax has become a way to control exiles abroad. The fighting mentality of a liberation fighter turns out to be no virtue for a democratic politician As long as there were no fundamental differences of opinion, Eritrea was a people’s democracy. Repression was not necessary because there was no opposition. The strong nationalism of the Eritreans dominated everything. But things went wrong when the liberators took on the roles of government soldiers and politicians. The fighting mentality of a liberation fighter appears to be no virtue for a democratic politician, as has already been shown in numerous countries in Africa led by former liberation fighters. That sense of a common goal, that idealism, the bush in which topics could be discussed openly: all these characteristics of the liberation struggle have become more of a trauma than a guideline under President Isaias. Those who do not conform are reminded of the hard struggle in the bush. The leaders abused the ideals to turn Eritrea into a cold police state. The country that many Africans saw as the continent’s hope in the last century is now its biggest disappointment.  All pictures by Koert Lindijer This article was first publsheid in the Dutch newspaper NRC on the 23th of February 2024 |