Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

In the narrow streets of Mopti, the sweet smell of cow dung mingles with that of the exhaust fumes from mopeds. Opposite the mosque, some youngsters play a game of table football. Mamoudou Fané strolls with his work tools into the house of prayer. “There goes the Wahhabi plumber”, the young people mock at him. An irritated Fane throws back his arms. “In the mosques of Wahabites I get work and food,” he retorts. “I am poor and have to feed a family.”

“Turncoat!” shout the boys.

Mali witnesses a steady religious revolution that may have dire consequences for the entire Sahel, and may eventually also pose a danger to Europe. The predominantly Muslim country was once a cradle of religious tolerance. In recent years there has been an insidious change with the advent of the fundamentalist Wahhabism from Saudi Arabia. The religious situation in Mali last year came under stress because of the rise of armed Muslim extremist groups from the north which had the whole country in their grip. It was only the military intervention of France that contained it.

Centuries ago trading empires developed around the cities of Djenné, Mopti and Timbuktu. The basis of the wealth was their geographical position which lay between Africa above the Sahara and sub-Saharan Africa. Islam arrived with the traders from the north. The black population absorbed the faith and merged it with their own religions, an interaction of religious and spiritual influences, and thus created an African Sufi form of Islam.

Hundreds of years later, Islam again comes to the Sahel, this time with an unstoppable mission mentality and the way paved by money from Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Pakistan. Foreigners, and also Malians who received scholarships to study in Saudi Arabia, introduce this strict form of Islam, and condemn the sufi’s.

These fundamentalist beliefs – Wahabism, Salafism and the Tabligh movement – hold different methods and rules. Wahabites and many Salafi’s are against the spread of the faith by arms. The Wahabites are not the same as the extremist Muslim fighters linked to al-Qaeda, which last year occupied northern Mali. The question is whether the rise of fundamentalist Islam is a fertile breeding ground for terrorists. This applies not only to Mali, but to the entire Sahel. Wahabites and extremist Muslim fighters propagate a ‘pure faith’ and are sowing hatred and division.

Photo’s Ilona Eveleens

Plumber Fané takes me to the bazaar. Abdourame Touré tinkers with an old radio in his stall. He leads a group of young and fundamentalist Muslims of Mopti. He is Wahabi but prefers not be so called, because a bad smell sticks to this name since last year when Muslim warriors occupied northern Mali. In the occupied towns and villages, the extremists always prayed in the mosques of the Wahabites.

“God has willed it so,” said Toure about the occupation. Yet he condemns the Muslim fighters. “The Quran dictates that you should not attack a city with Muslims and Christians living there without first sending a messenger. Every Muslim must adhere to that rule. There is only one possible interpretation of Islam. ”

From the minaret flows the unctuous voice of the imam through the alleys. Passers-by pull at a donkey cart, freeing it from the open sewers where it got stuck. We walk to the women’s collective Aicha, a project funded by Saudi Arabia, where women in black robes sit on mats. Director Puritine Traore is veiled. “I am a Wahabi,” she says. She and her husband, who also work there, had lived in Saudi Arabia for five years. “Islam is better developed there than in Mali. Mali needs more Islamic education, our country is too secular”. The eighty girls, who work there, receive food and lessons in the Quran. “You see now how well the Wahabites take care of us,” says Fane jubilantly.

We plow through the crippling heat to his poor neighbourhood. Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world and the same applies to the other countries in the region. Hasseye Kanita, a social worker, invites us into the shade. “We see a rapidly changing mentality in Mali,” he says. “Wahhabi youth use aggressive language and shut themselves off. More and more women are veiled. In villages and towns we see new mosques of Wahabites springing up; the imams are paid by Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Pakistan. They provide food and scholarships for young people in the Middle East”.

Malians are remarkably friendly, open and welcoming. Can a thousand year old culture of tolerance be replaced in such a short time by a religion of intolerance? All attendees under the roof say democracy is to blame. The coup of 1991 marked the end of 23 years of military rule. “First under the civilian President Alpha Konaré, followed by Amadou Toumani Touré, religious movements from the Middle East were free to recruit supporters from Mali with their money,” said Kanita. While six Islamic development organizations were working in Mali before 1991, this had increased to one hundred and six in the year 2000. Ninety percent of Malians are Muslim, twenty percent of them have converted to the Wahhabi denomination.

The Supreme Council of Muslims (financed by Saudi Arabia), which is led by Imam Mahmoud Dicko, calls for increased influence of Islam in politics. When in 2009 the parliament passed a law that allowed inheritance rights for women, Dicko promised that “Mali will burn.” He organized mass demonstrations which led to government repealing the law.

“Dicko speaks with many tongues,” says Kanita. “But he is right when he says that the political class has failed. Clergy are closer to the people than politicians”. What to him is the most important breeding ground for the fundamentalists? “Poverty and the absence of the state.” follows his swift response. Plumber Fané nods in agreement. It’s seven o’clock and the imam calls to prayer. We decide to go to the nearest mosque, a house of prayer of the Sufis.

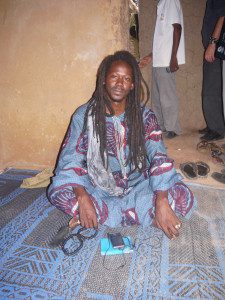

A priest wearing long dreadlocks sits fidgeting with his prayer beads. It is hot and sweat is dripping from my body. Imam Sidibe Abedkader apologizes. “We pray under a simple shelter, we have no money for an air conditioner as in the Mosque of the Wahabites”. He points to the plumber. “You tell us how comfortable their mosques are”. He then launches into a tirade against Saudi Arabia. “That country wants to dictate to us its form of Islam, and wants to drive us Sufi’s out. The Saudis are colonialists”.

God expresses Himself in the Quran in metaphors, according to the Sufis. They don’t take the holy book literally, like the Wahabites do. “You have to discover God in yourself. Everyone is a bit of light. That means you have to be tolerant and explain the Quran in a spiritual way”, the imam teaches his followers. “We Sufis have to start thinking of playing a role in politics, otherwise we will be driven out by the Wahabites. Had the Muslim warriors reached Mopti, then my mosque would have been closed by now”.

The next day I travel to Konna, a half hour drive from Mopti. Konna was the turning point. When the extremist Muslim fighters in January occupied the town of 30,000 residents with the aim of attacking Mopti, it was the French army that put a stop to it.

In the heavily damaged office of mayor Sory Ibrahima Diakite’s hangs a portrait of Francois Hollande, “the president to whom we owe our freedom”. The mayor narrates how the extremists had sacked him from office, and how from that time onwards the imams had exerted authority.

Did the fighters receive support during the occupation? “Sure, some young people joined them. They knew their way around very well here. A marabout assisted them”. Were the Wahabites in cahoots with the Muslim fighters? “The extremist fighters belong to the same clan as the Wahabites. In the Sahel borders mean little, and since the caravan trade centuries ago there has been a lot of travelling. The Wahabites are often traveling traders, therefore their influence reaches far. They usually have a light skin and come from Mauritania and Algeria. Since the intervention of the French, many have disappeared from Konna”.

In the market many shops are closed, the owners have absconded. I find Issa Dembé there, one of the 500,000 persons displaced by the war. He fled Gao, the city where the Muslim fighters were welcomed by some inhabitants during the occupation. The Wahabites had in recent years strengthened their presence in Gao. “They say that our prayers are not valid”. Dembé tells about the presence in Gao during its occupation of the Nigerian terrorist group Boko Haram and fighters from Yemen. He dares not go back, “because the extremists have sleeper cells and will try to strike back”.

A few days later in Bamako, I come across the same fear of extremists in hiding. Imam Mai Bah talks about spies in the capital. “The extremist still want to take over Mali,” he says. He is head of the National Organization of Young Muslims. “The Wahabites and the Salafists are accomplices of the terrorists”. He points to the training centres near Wahhabi mosques in Bamako. “They do ideological manipulation. They have some kind militia there. With their inflammatory rhetorics they manipulate the uneducated and unemployed youth. They work on the expansion of the Arab influence in Africa. The Arab world still thinks that African Muslims are not real Muslims. ”

Is Mali the first toppled domino in the Sahel? Or was the occupation of the north a typical Malian problem? The rise of radical religions, the collapsed education system and extreme poverty are not the only explanations. Because of the weakened state, an alternative economy in the form of trafficking in drugs, weapons, cigarettes, hostages and migrants had developed in Mali. Citizens and radical Islamists were working with the criminals. A diplomat in Bamako says: “In Mali entire villages benefitted from that type crime. These networks need to be fought; otherwise the terrorists can seize power again. ”

France took the initiative with its intervention, and donor countries pledged 3 billion Euros in aid for Mali. Nobody knows exactly how to work on stabilisation in Mali, and in the region. For many Malians it is clear that freedom for the various apostles must be constrained. Zeïni Moulaye, a former minister, warns of the consequences of the influence of the religious radicals from the Middle East. “Let us demand from them that they respect our culture and laws. Such as a separation of state and religion”, he advocates. “There is the letter and there is the spirit of the Quran. We Muslims in Africa know the difference very well.”

Vulnerable region

The immense size, weak states, poverty and the proximity of the turbulent Arab world makes the region of the Sahel and the Sahara vulnerable.

In Mauritania military coups take place regularly. Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz came to power in 2008 by a military coup. He had himself elected in 2009. There was an attempt on his life last year under unclear circumstances.

In Nigeria the battle is still raging with the terrorists of Boko Haram.

In Burkina Faso, the authoritarian and corrupt President Blaise Compaoré has to resign in 2015 according to the Constitution. Compaore, who came to power since 1987, combined democratization and repression to establish stability, but his order revolves exclusively around him and his family.

In Niger extremist Muslim fighters conducted some bold attacks in recent months on a uranium mine of the French company Areva, and released prisoners in the capital Niamey. Niger has an army with 7,000 troops to guard their borders with the violent countries Nigeria, Mali and Libya.

Chad. President Idriss Deby rules since 1990 and suppresses the opposition. Twice he was almost overthrown by infiltrated rebels in the capital N’Djamena.

In Sudanese region of Darfur ten years after the outbreak of conflict between the government and militias on one hand and rebel groups on the other is still a source of instability. Hundreds of thousands of people stay in IDP camps. In recent months there was heavy fighting between rebels and government and between tribes.