A red carpet was laid out at the airport of Banjul and a brass band played. That is how Yahya Jammeh was escorted out of the Gambia on Saturday night January 21. The dictator, with an oversized ego and a childish love for cars, wanted to take one of his Rolls-Royces with him, but the new president Adama Barrow put a stop to that.

The dignified departure of Jammeh from Gambia after 22 years was made possible by international negotiators. After his pledge Friday January 20 on television that he would resign – he had his rule extended after his election defeat by a declaration of a three-month state of emergency – yet he refused to immediately leave the country. He succeeded to get a good deal with the negotiators of the UN, the African Union and the regional grouping ECOWAS. A document of the three organizations praises Jammeh for its goodwill and statesmanship.

In the village of Tujereng, forty kilometers south of the capital, five torture victims throw their hands in the air -out of disbelief- when they hear about the document. “How is it possible that he could leave this way?”, says an old man called Ibrahim Jaban. “I want to do to him what he did with me. I want to kill him.” Jaban lost an eye and broke his shoulder blade during torture.

In the agreement, the former President is addressed as ‘HE Sheikh Professor Alhaji Dr. Yahya A. J. J. Jammeh‘. The agreement of the three organizations promises to argue with the new government under Adama Barrow that Jammeh’s “lawfully acquired property will not be confiscated” and that he may return to Gambia. The new government should “respect the dignity, security, respect and rights of the former president.”

When Jammeh seized power in 1994 as a 29-year-old soldier, along with a small group of supporters in the army, there was less than a thousand dollars in his bank account. After a 22-year long rule under which hundreds of opponents “disappeared”, he is now the largest shareholder of the country’s economy. Under the name of his native village Kanilai he owns large farms, bakeries, a fashion store, gas stations, fish farms and a fleet of trucks. Farmers lost their fields without compensation when the Kanilai company wanted to start a farm. Businessmen who refused to sell their successful company to the president ended up in jail.

In the village of Tujereng long silences occur during a group discussion, punctuated by deep sighs. Chickens flapping around appear invisible. Finally, Kafu Bayo in a pink caftan begins to talk. “This is very painful for us.” Then he is silent again. Kafu Bayo is 76 years, Modou Ngum 35. Both are missing an eye, Modou Ngum flutters with the other one. “I have no network anymore,” he says. “He means that he, like me, is suffering from amnesia,” Kafu Bayo explains.

Kafu Bayo and Modou Ngum went to Banjul last April to demonstrate with banners like: “Gambians are starving” and “We want reform of the electoral system.” Even before they could begin their march, they were arrested by secret agents. This happened along with thirty others and with the prominent opposition leader Solo Sandeng. They were taken to the headquarters of the National Intelligence Service.

“We each got a black bag tied over our heads. They beat us. Then they tied us to a table and asked for our tribal ancestry and what political party we belong to. Then they started kicking”. Kafu Bayo shakes his head and nervously puts his Muslim headgear on and off. He shows a scar from a hot iron, all over his body are scratches. “’We will kill you, all of you’, they said. I heard Solo Sandeng screaming and crying. They say they pulled his heart out.”

The ones who survived moved out after two weeks to the notorious Mile 2 prison in Banjul. There is a special space there for political prisoners, which Jammeh recommended to his opponents as “the crocodile pool.” Every day they were mistreated there. When a security guard accidentally dropped a kind word to the prisoners, he was beaten too by his superior. “Our food they mixed with sand.”

After several weeks the case against Kafu Bayo came to court, presided over by a Nigerian because most Gambian courts had fled the country. Bayo’s daughter had already been dismissed from her job as a teacher in Tujereng because of the arrest of her father. His wife and another daughter who came to the hearing were arrested in the court and detained for several days. “It feels so bad that they got my family involved, they had nothing to do with our planned demonstration.”

Each received three years in prison, but op appeal they were freed after the December elections. Nightmares keep them awake at night. Modou Ngum had to give up his job in construction. “He has no strength,” says Kafu Bayo. “He has become a different person; his character is entirely changed. I never see him laugh anymore.” All the men say their largest trauma experience is that they did never see the agents of the secret service who tortured them; because of the black bags on their heads they will never know who has done this to them.

Jammeh operated several terror groups inside his army, of which the paramilitary group the Jungullars was the most feared. In Tujereng lives Mailik Jatto, a notorious member of the Jungullars. “In 2004 he killed the renowned Gambian journalist Devda Hydara,” says Bayo Kafu. I request everybody around to go and visit him, but my suggestion is rejected with spontaneous boos by all those present.

In Banjul Khalifa Sallah, spokesman for the coalition of parties around Barrow, admitted the existence of the controversial document “But Barrow has not signed it”, he stressed.

This article first appeared in NRC Handelsblad on 23-1-2017

Pictures by Johannes Dieterich

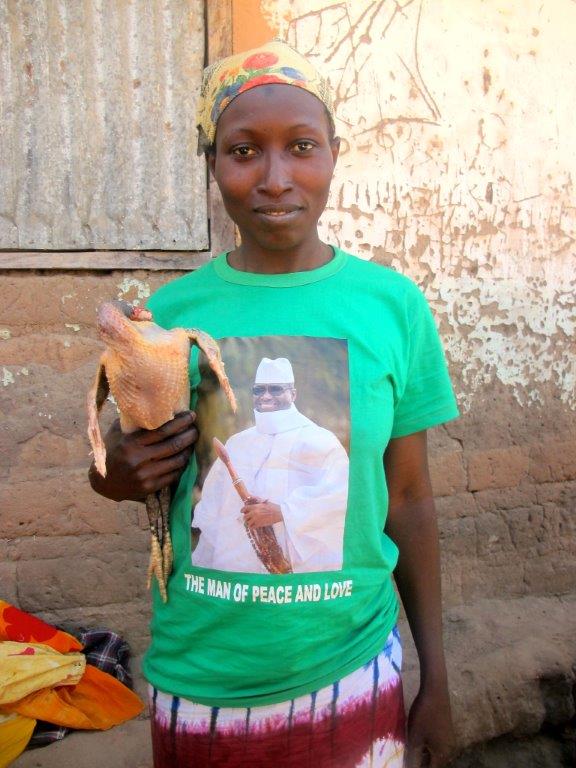

Picture 1: Supporter of Jammeh

Picture 2: Senegalese tank, part of Ecowas intervention force

Picture 3 Streets of Banjul were empty for several days