Meles Zenawi was, as the Ethiopian culture prescribes, distant and polite. But after an interview he also could talk straightforwardly. “I am a communist and have no reason to hide it,” the guerrilla fighter said in 1990 in a Tigrayan village at the time of the collapse of the Communist empire. Later as Prime Minister in the capital, Addis Ababa, after a conversation of three hours, he put his feet on the table and said: “I just had the French ambassador for a visit. What an asshole that guy was. These Western envoys think they can impose anything on me. Do you have a cigarette? ”

Meles was not the leader to break the traditional authoritarian power system in Ethiopia. Under the feudal regime of Emperor Haile Selassie (1930-1974) Ethiopians could not think for themselves. Under his successor, the ruthless military Marxist Mengistu (1977-1991), no one ventured to express his own opinion. Under Meles Zenawi it was also better not to deviate too much from the ideas of the ruling party. Rulers in Ethiopia tend to rule like gods.

But Meles did put that medieval-poor country on the road to economic development for the first time. He liked to be seen as a peasant leader who had to take on the urban elite in Addis Ababa. But eventually he turned out to be an authoritarian ruler in the imperial Ethiopian tradition. At a time when liberal values finally took a foothold in Africa, he led his country as a scientific socialist with tight management methods.

For Meles, the world was one big scientific book. Everything would be fine if the guidelines outlined by his party were followed to the letter. In May 1991 the rebels of his peasant movement the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) – admittedly with considerable Eritrean assistance – expelled the brutal military Marxist regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam from Addis Ababa. But the liberation was not celebrated by the whole population: the Amhara who ruled Ethiopia for much of its history, were close to Mengistu and were not going to cheer “the hillbillies from the countryside of Tigray” as they entered the city.

At the first demonstrations against Meles, immediately after the liberation, his fighters shot several protesters dead. “It’ll be okay,” reassured the Prime Minister in an interview, “later the demonstrators will understand that we have the right on our side.”

Ethiopia was still in chaos two years after his takeover. Ethnically based rebel movements fought in all parts of the country against the “domination of the Tigrayans”, a group that consists of only 5 or 6 percent of the entire population. His government had introduced a unique model of ethnic federalism to cool tension between different groups, but initially this ethnic democracy caused the opposite and led to more division.

“Don’t you feel like a professor sometimes,” I asked him in May 1993, “with abstract ideas for the long term. Are you not distanced from real, ordinary life?” Meles replied: “But the ideas come from the people. They are very simple, logical ideas. It simply means: let the farmers be themselves. What is the purpose of democracy if it means nothing for the people, when democracy is only a plaything for the elite? The lower the centre of power, the better.”

Meles could explain everything away. He was a liberator but his reign had a tyrannical trait. As Prime Minister he was as removed as Haile Selassie had been. Few countries in Africa are as repressive as Ethiopia. And the suppression increases. While the rest of the continent modernizes, Ethiopia seems to return to earlier times: no dynamic press, a fearful opposition, a command economy, a tight bureaucratic hierarchy with the undisputed leader at the top.

Talking with opponents has become dangerous. If you sit in a coffee shop for a chat, informers for the secret service come and sit near you and start fiddling in their bags to switch on a tape recorder. But Meles denied that his government was spying on the population. He accused me of being paranoid. “How can I take that feeling away from you?” he asked in 2009. “Even if we wanted to, we don’t have the capacity to do such intelligence work.”

His Government promulgated harsh press laws and arrested journalists. Foreign development organizations were curtailed because they brought liberal values. What about the increasing repression? I asked him in 2009. “I understand that some people explain what is happening here in Ethiopia as repression,” he said. “Several people were arrested, they harboured plans to murder government officials.”

Meles did not portray himself as a beloved leader. He was enthroned above the people. That was different in his time as a guerrilla leader. Had he become like an arrogant emperor? “In Addis Ababa I don’t mix with the population, for security reasons. But in the countryside the farmers are free to ask me questions.”

His ruling party established many large firms, which control a major part of the economy. Vested interests and the arrogance of power seem to have destroyed the ideals of the liberation struggle. As in many African states with former fighters in power, his liberation movement was falling prey to nepotism. Meles had read enough books to detect that danger.

“Absolutely, that danger exists,” he answered in an interview three years ago, “that’s why a movement has to renew itself, including its leaders.” He confirmed that he wanted to retire, “if my party agrees. I want to be the first Ethiopian leader in history to resign voluntarily.”

Meles arranged everything to perfection in his political life and presumably he had his succession concocted from his deathbed. But not everything can be settled according to the written down theories of control. Meles was a chain smoker. In every conversation I had over the years he would say that he had almost stopped smoking. After which he lit a cigarette. According to one of the many rumors that are floating around this tightly controlled state, the leader who only reached the age of 57, died of cancer.

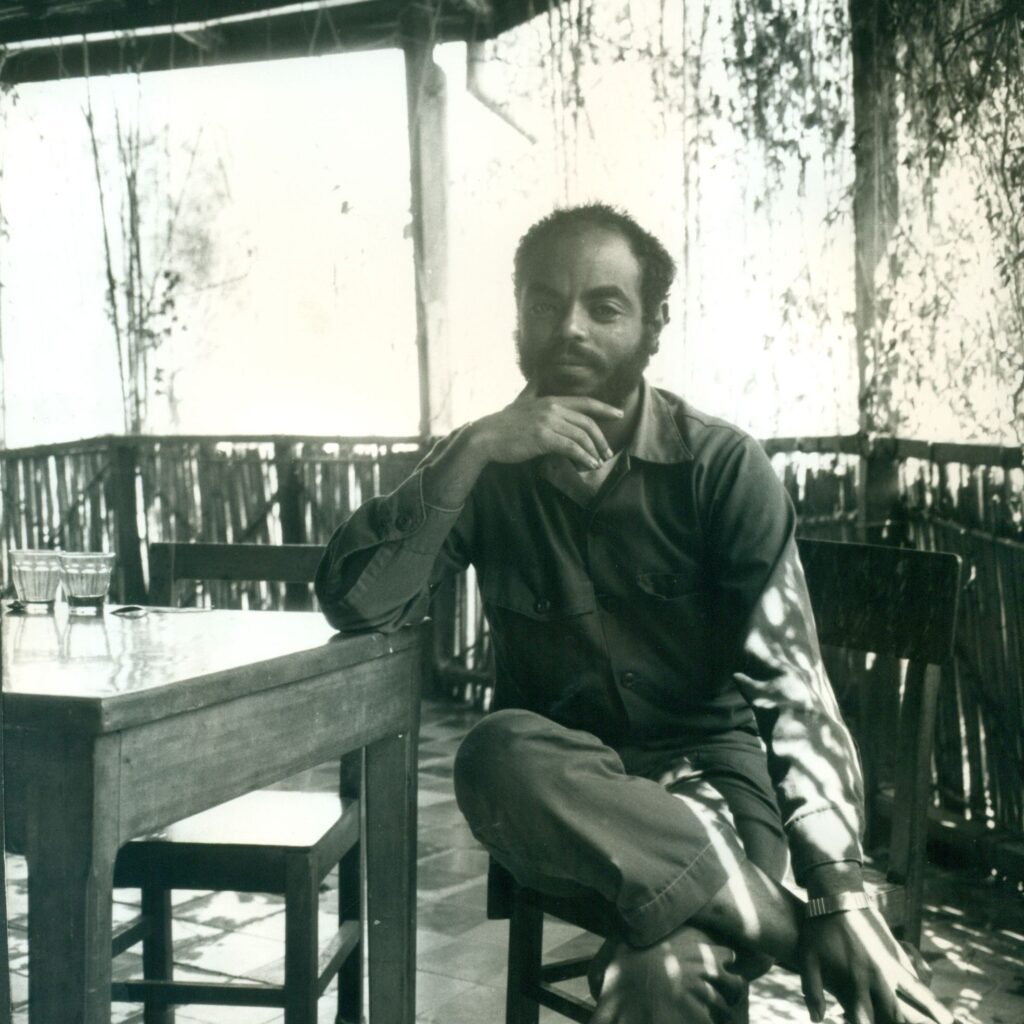

Picture of Meles Zenawi by Koert Lindijer 1990 in Makele

Also see the article on Meles by Richard Dowden here on The Africanists