The 1994 Rwandan genocide against the Tutsi led to the murder of more than 800,000 people, an estimated 70% of the country’s Tutsi population. The unprecedented violence and mass killings of Tutsi and non-extremist Hutu were carried out over 100 days between April and July 1994.

An estimated 250,000–500,000 women and girls were raped during the genocide by the Hutu-led militia group Interahamwe, local police officers and individual men. Hutu women were also abused by soldiers from the Rwandan Patriotic Front. Up to 90% of Tutsi women who survived the genocide suffered some form of sexual violence.

Although rape was often immediately followed by murder, some girls and women survived, and were told by their aggressors that they would “die of sadness”.

Sexual violence was used as a deliberate strategy and weapon of genocide to degrade, humiliate and destroy the Tutsi. It had devastating physical, psychological and socio-economic effects.

Conflict-related sexual violence affects individual rape survivors, as well as entire families and communities. It leaves complex intergenerational legacies. This is particularly apparent for the estimated 10,000 to 25,000 children born of conflict-related sexual violence in Rwanda. In the absence of legal access to abortion, many women who were raped gave birth in secret, committed infanticide or abandoned their babies.

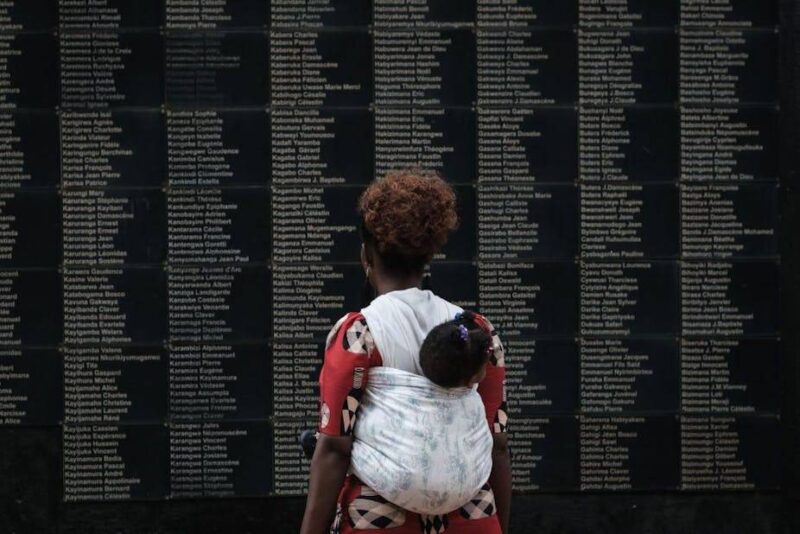

Children born of the genocide – often referred to as “children of hate” by community members – became living reminders of the suffering survivors endured at the hands of their perpetrators. Yet, little attention has been paid to these children.

Over the last two decades, I have been researching the impact of war and genocide on children and families, alongside the fallout of conflict-related sexual violence and its intergenerational implications. For this latter work, I have drawn on hundreds of interviews, focus groups and arts-based methods with children born of conflict-related sexual violence in multiple post-conflict contexts, and mothers who gave birth to children born of these attacks.

I completed a study in Rwanda that explored the realities of children, both boys and girls, born of conflict-related sexual violence. I researched how 44 mothers and 60 children continue to be affected by post-genocide discrimination, violence and socio-economic marginalisation.

These girls and boys – now young women and men – have reported that Rwanda’s annual commemoration, which takes place in April every year, rarely acknowledges children born of conflict-related sexual violence. Their desire to be recognised, seen and protected was repeated frequently in my research.

My findings show that girls and boys sustained the indirect consequences of (gendered) injustices committed against their mothers, making stigma and social exclusion a shared and intergenerational experience.

The legacy for mothers and their children

Ethnic tensions between Rwanda’s majority Hutu and minority Tutsi date back to the country’s colonial past under Belgium. The Belgians’ favouritism for the Tutsi sparked decades of conflict and discord, culminating in the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi.

The mothers who participated in my study gave accounts of how, as survivors, they were often rejected and stigmatised when family members learned they had been raped. They were frequently driven out of their families and communities.

As one mother explained:

It was hard because everyone was abandoning me. They were saying that I was a wife of Interahamwe (Hutu militia). They were saying that I (should) die rather than give birth to a child of a killer. So I raised her, and I hated her.

These experiences had intergenerational implications. The violence and stigma experienced by mothers directly affected the lives of their children. Children in my study reported that their own family and community relationships were marred by multiple forms of violence, ostracisation and discrimination:

One day, when I was with other children who are neighbours, one child called me ‘Interahamwe’. What I knew was that Interahamwe were killers during genocide against the Tutsi. So, I went home and told my mother about what happened to me. Instead of talking, she cried a lot.

Given their birth origins, children born of genocidal rape also struggled with their sense of identity. Who were they? Where did they belong? Children’s identities and heritage were often linked to their perpetrator fathers. This mother explained:

Living (with my family) was hard because even my family didn’t want to see my child … And the hardest part was that the person who raped me (during the genocide) killed my grandfather. So, every day, I remember that, and it is very painful. And when I see my daughter, I see her father in her … There are things that you can forget, but those are things that you live with, and forgetting them is not easy … I am married, but my husband doesn’t accept her. So sometimes I think that it is her fault, the things that happened to me.

Children experienced many forms of abuse, with girls reporting being given heavy domestic duties at home and being victims of sexual violence by stepfathers.

Many children said they lived in poverty, were unable to access school fees, and were excluded from systems of support. For example, the fund for assistance to survivors provides support only to individuals who were alive and affected by the genocide between October 1990 and December 1994. This means children born of conflict-related sexual violence who were born in 1995 are ineligible for genocide-related social and financial assistance.

Shared strength

And yet, against great odds, many mothers and children found strength and support in each other. Some mothers referred to their children as a “gift from God”:

I hated her when I was pregnant. But when I found out after the genocide that everyone in my family was dead – my parents, my seven siblings – I started wishing that she could be born so that I can have a family. I called her (name) because I loved her so much … because of how she was born. I was raped, so not being able to find out who is her father makes me feel like I’m her mother and her father.

In turn, many children held strong bonds with their mothers, and emphasised the support and care they received:

My mother is my best friend. My mom was requested by many members of her family to reject me, but she never did it. Instead, she took care of me like other children. She showed me love and I love her as well.

Given the vast scale of Rwanda’s violence, its intimate nature of neighbour killing neighbour, the devastating losses and lasting scars, the challenge of (re)building the social fabric is evident and ongoing, decades later. In the face of profound adversity, mothers and children have shown immense and shared strength, capacity, and resilience in overcoming their histories of violence.

This article was first published on the Conversation: