Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Development aid by the white Western world to poorer countries is in retreat. It marks the conclusion of an era. What drove Westerners to dedicate a portion of their lives to work on the other side of the globe?

Alie Eleveld (65) is stuck with urine and feces in her refrigerators. She no longer receives donor funding from the United States to analyze this material in her lab in Kisumu, a city in southwestern Kenya. Her organization previously gathered samples for detecting cholera and other potential epidemics, but the research has halted.

She calls the abrupt halt to all American aid earlier this year “criminal and unethical.” Eleveld is retiring this month, concluding a forty-year career in medical development work in several African countries, including Kenya. She and others look back on more than half a century of development aid, which comes to an end with Trump’s dismantling of the American aid agency USAID. This step marks the end of an era in which, since the 1960s, American and European aid to the global South has been part of multilateral relations.

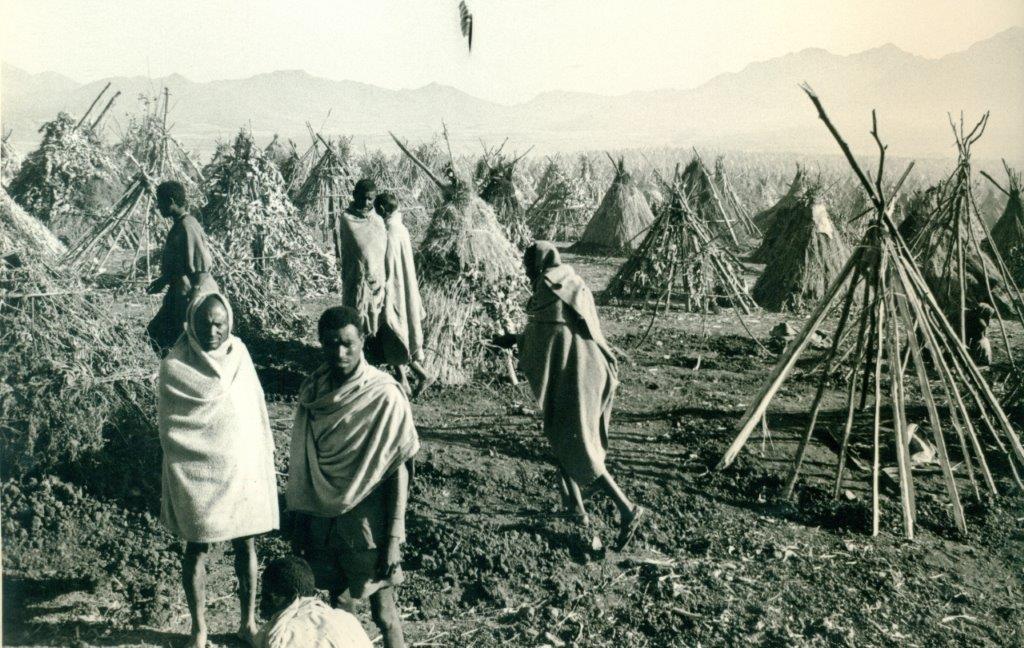

The aid industry exploded after the famine in Ethiopië in the 80’s

Helping was normal

One should assist others, even if the person in need is far away on the other side of the globe. This idea was widely accepted in the previous century. “I always wanted to work in development aid,” says Eleveld. “I wanted to make myself useful, sought adventure, and in 1984, at the age of 26, I left for Zambia.” Eleveld’s parents during World War II used to help Jews hide on their farm in Hooghalen, in the province of Drenthe in the Netherlands. This proved to have a lasting influence on her life.

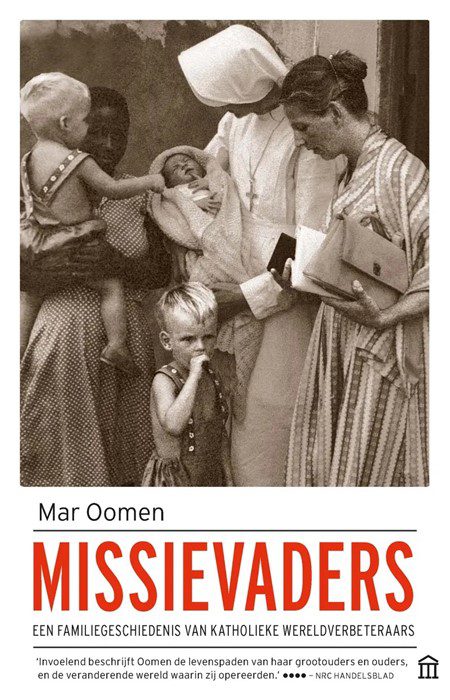

Mar Oomen (64) received a legacy of charity early in life. Instead of becoming an aid worker, she chose to be an anthropologist and authored a book about her two missionary fathers. In 1933, at the peak of Catholic missionary efforts, her grandfather traveled to Indonesia fueled by his faith. Later, in 1958, her father served as a Catholic tropical doctor in Tanzania, where Mar was born on Ukerewe Island in Lake Victoria. “It all started with wanting to do good, wanting to make a difference in the world. The missionaries were convinced of the existence of God and the faith of the Catholic Church,” says Oomen. “That was the only good church and the only correct faith. They wanted to introduce others to that God and that faith.”

First the missionary and later the secular development worker entered Africa with a Western worldview in mind. After the wave of decolonization in the early 1960s, the departing colonists hoped to maintain a degree of influence through development aid. The technology transfer by white aid workers could help close the divide between the wealthy and the impoverished in the world. This method depicted Africa as a charity case, with the swiftly arriving white savior taking center stage, reinforcing colonial and slavery stereotypes of white superiority.

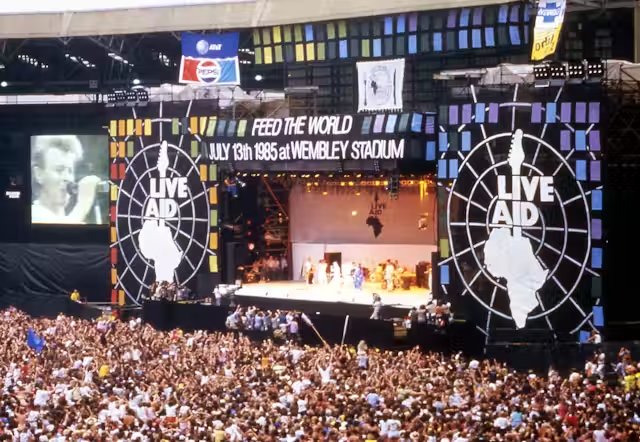

Where once the missionary magazine proclaimed mercy, now new media threw themselves into charity. Compassion characterized the 1980s when artists raised money for hungry Ethiopians, such as Live Aid in 1985. In collaboration with television stations, the music industry was able to achieve more at that time than diplomacy, which was often driven by Cold War politics. With their benefit concerts, they kicked Western leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who refused to help, in the buttocks. This pressure from artists led to a large-scale aid campaign, after which Africa found itself at the center of a orchestrated global outpouring of compassion. This wave gave rise to an industry revolving around emergency and development aid, circulating billions of euros. Extremely poor states like Burkina Faso and Mali were labeled “Oxfam countries” due to their almost total dependence on foreign NGOs, such as the British Oxfam. Because Western development ministers could turn the aid taps off or widen them at will, they gained excessive influence over Africa.

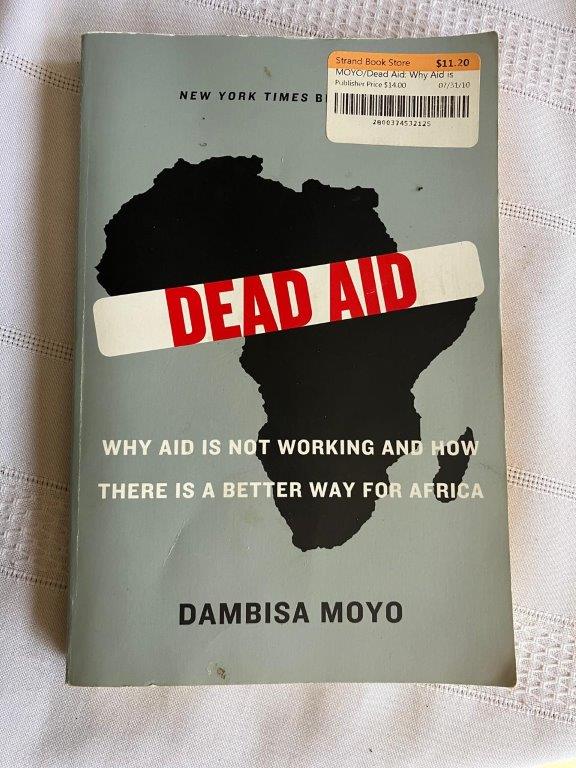

But gradually, criticism of development aid grew. In 2009, Zambian economist Dambiso Moyo published the controversial book Dead Aid. “Aid breeds laziness among African policymakers,” she wrote in her book. It stifles private initiative and increases dependency. “This partly explains why there’s a kind of nonchalance, a lack of urgency, among many African leaders in addressing serious problems. Because aid flows are seen as a guaranteed source of income.”

There she touches on one of the most sensitive criticisms of aid: the dependency syndrome.

The Kenyan government is so dependent on foreign donors that it is unable to respond properly to the halt of American medical aid due to fear. The Ministry of Health’s budget depended on donor funding for twenty percent, and rather than filling that gap, the overall budget has been cut.

Dependency

It seems a donor country might soon emerge to take the place of the old ones. However, those times have passed. The US is not the only one making major cuts; other Western countries are also greatly slashing their development budgets. For instance, the Netherlands has been reducing its development cooperation by hundreds of millions each year since 2023, and both Germany and the United Kingdom have also decreased their aid in the last few years.

The consequences are dramatic. In the northern Kenyan refugee camps of Dadaab and Kakuma, tens of thousands of people have been put on halved rations. American food aid for soup kitchens in Sudan has stopped, as has the supply of HIV medication in Kenya and South Africa. The continent is on the verge of a medical emergency. “In Kenya, we still have several months’ supply of HIV medication in stock,” warned Githinji Gitahi, head of the medical organization Amref, in May. “If those funds run out, people will die. There will be demonstrations, and the crisis will undermine the political system. Because governments don’t have the money to fill the gap.”

Eleveld began her development work by traveling to remote villages on the Mozambican border, hanging a scale from a branch, treating malnourished children, and providing basic healthcare. “There was still plenty of money available in development aid back then, but we weren’t always very economical with it,” she says.

That wastefulness is one of the things Eleveld objected to in development work, especially the aid involving USAID. “Sometimes foreign organizations sent a separate team to affix their group’s logo and banner to projects. And another team for policy, one for development, and a technical team. That leaves little money for those truly in need. You then start wondering what happens to all that money. This was especially the case with American development aid workers. They lived in expensive houses and drove around in large SUVs. They were allowed to take an entire container filled with even toilet paper and tomato sauce. That was a huge waste.”

Another critique of development aid is the desire to give. Those who give gain people’s favor. A person born in a wealthy region automatically holds a privileged position compared to those in poorer areas, just by being a giver. These dynamic grants the giver influence and power, a status they would never attain in equal conditions.

“Yes, I enjoy giving; I’m somewhat guilty of that,” Eleveld agrees. “And now that I’m returning to the Netherlands, I’m also a bit tired of how some people became dependent on my generosity. But I’ve also always tried to change people’s behavior to prevent dependency on development workers. I think I simply observe a lot of misery that others don’t see. Yesterday, during my farewell tour of projects, I met an elderly blind man who lost his home and his son during floods. Thanks in part to my efforts, he now has a home again and can see again. That gives me a tremendous feeling. He’s happy, and so am I.”

Kenyans can support one another on their own. Long before Western aid appeared in the last century, rural Africans were concerned about each other’s well-being. There was a stronger sense of social unity back then: farmers and nomads looked after one another, motivated by community spirit. A trace of that connection still exists.

The American aid machine started full force in the beginning of the 60’s under JF Kennedy

Back to old habits

Kenyan Florence works for a charity in Kenya itself, the country that, according to the Charities Aid Foundation and the World Giving Index, has the most generous inhabitants in the world. “It’s good that the dependence on USAID is now disappearing; the closure is a blessing in disguise,” she argues. “We now have to fall back on our own old habits; we have to bring back African communalism.”

Kenyans often help pay for the medical care of their sick relatives. Every day, requests for assistance are seen in newspapers and churches, and politicians also take part in public fundraising. “We’ve always helped each other; it’s deeply rooted in African culture,” says Florence, who wishes to remain anonymous for personal reasons. “We pay each other’s school fees, we give generously to the community and to the church. Most schools in Kenya are funded by the churches. Even when someone wealthy marries, poor Kenyans also contribute to fundraising drives, even if it’s just a few shillings. Charity makes people feel good, even more so for the giver than for the recipient.”

What is left of that compassion now that development work is fading away? Oomen, who comes from a missionary family, believes that the desire to help will not vanish.

“In my parents’ time, it was a duty based on your faith and social position to care for others,” she says. “Since then, that feeling has evolved. It kept pace with the changes in the world and within yourself. But being there for others, wanting to make a difference, that remained.”

You keep some of your parents’ motivation to assist others. Oomen chose anthropology. “I want to make different worlds and cultures more accessible to each other, by providing insights so people can come closer together.”

Then she strikes a slightly ironic tone and says: “Maybe we should go back to church after all, in the sense that in the past, you were simply obligated to take care of each other.”

This articel was first pubished in NRC on 20-8-2025