“They tell us they are hunting the FDLR, but it is peasant farmers who are dying.”

It is the place where the insurgency began nearly four years ago.

It is where the rebels have built one of their largest training camps. And it is where they still wage some of their fiercest battles against rival armed groups.

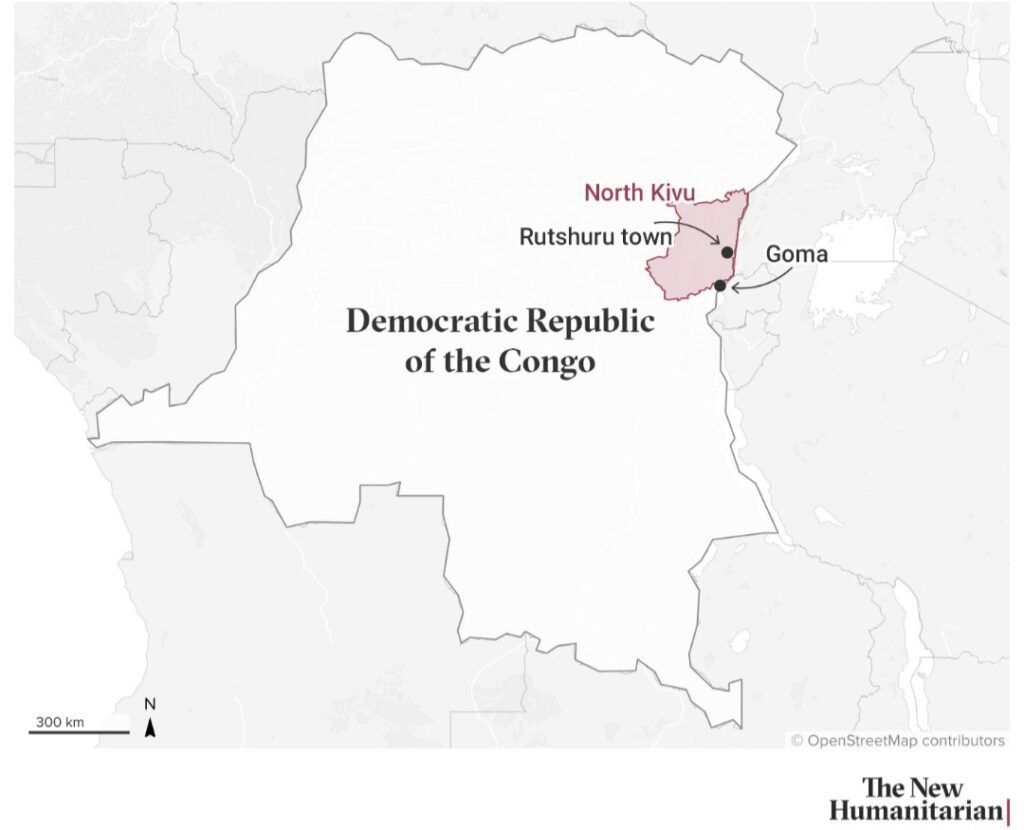

For hundreds of thousands of civilians in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo’s Rutshuru territory, the past few years have brought great fear and hardship under the occupation of the M23 – a rebel group driving one of the country’s largest insurgencies.

“Organisations that defended fundamental rights and freedoms have already stopped their activities, and human rights activists who are still there live in fear and despair about the future,” said an activist from Rutshuru, which is a mostly rural territory.

The activist was speaking to The New Humanitarian for a series examining how M23 rule is affecting people in more rural and provincial areas – places that have received far less attention than the larger eastern cities that are under rebel control.

Led mostly by Congolese Tutsis, the M23 began operations in eastern DRC in late 2021, citing a broken peace deal and discrimination against Tutsi communities. It has since formed a political wing with national figures who want power across the country.

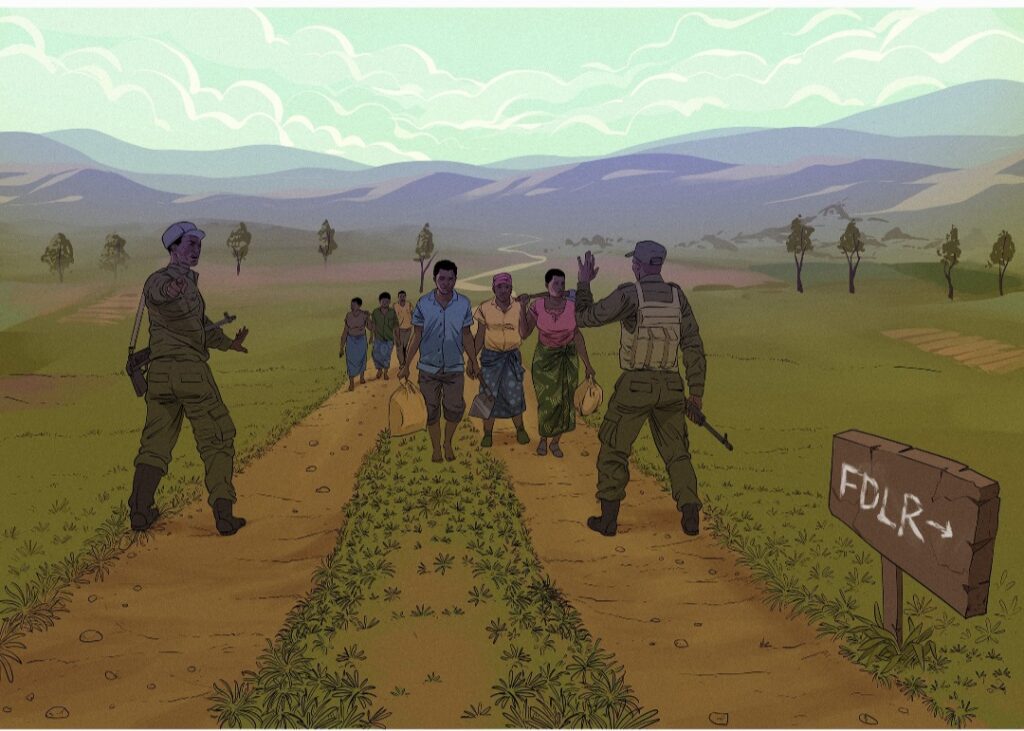

The group – armed and backed by thousands of troops from neighbouring Rwanda – is especially sensitive to the presence of the FDLR, a militia formed in eastern DRC by exiled Hutu extremists involved in the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

In parts of Rutshuru where the FDLR is present, the M23 has mounted repeated offensives that have hit local residents hard – with reports of mass killings of civilians and restrictions on access to farmland where the Hutu rebels are thought to be active.

Prisoners detained by the M23 in Rutshuru, meanwhile, described appalling conditions and cases of summary executions, while some farmers said their land had been appropriated by rebels to feed their fighters.

Some residents, however, noted various positive aspects of rebel rule, from efforts to curb kidnappings and banditry that have long been rampant in the area to temporarily lower taxes, though many doubt these changes will last.

“Aren’t they just pretending to cooperate and impose affordable taxes during the war, only to demand more later than what we used to pay the government in Kinshasa?” asked a local businessman.

Fears of ethnic cleansing

The M23 comes from a long line of DRC armed groups backed by Rwanda. Support began in the 1990s, when Rwanda’s new Tutsi-led government began pursuing the genocidaires crossing into DRC. The interventions led to wars that caused millions of deaths.

It is widely believed that Rwanda’s current support for the M23 is driven by geopolitical and economic interests, though the Congolese army has given it a pretext by allying with various militias, including the FDLR, to strengthen its ranks against the rebels.

In Rutshuru, some civilians had hoped that the area’s geographical proximity to Rwanda would have earned them more leniency under the M23 and Rwandan troops, but they have borne some of the harshest burdens of the rebellion.

A farmer from the village of Nyamilima said he had friends who were working in local fields in recent months when they were killed by the M23 during operations supposedly targeting the FDLR.

“They tell us they are hunting the FDLR in the bush but it is peasant farmers who are dying,” said the farmer. “There are many residents from here who went to do their farm work there and never came back.”

The farmer said family members of victims he knows weren’t allowed to give the deceased a dignified burial and arrange a proper mourning ceremony.

According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), the M23 summarily executed in July more than 100 mostly Hutu civilians in at least 14 villages and farming communities in Rutshuru’s Binza area, which includes Nyamilima.

Witness accounts and military sources told HRW that the Rwandan military participated in these operations, which also targeted women and children and have given rise to concerns of ethnic cleansing in the area.

Barred from their fields

Other Nyamilima residents said they have been barred from accessing their fields because of the operations, deepening a food crisis for people who were in many cases already desperately hungry.

“It was in our fields that we found corn and cassava to feed our family,” said a Nyamilima resident who had previously been displaced by the conflict and had only recently returned to the village. “Now we are suffering and barely eat once a day.”

Another Nyamilima local who has lived there since 1980 said the ban on accessing fields is affecting the spirit of solidarity that helps residents support displaced people and returnees.

“We used to harvest food in the fields and help the displaced in our villages, but right now, we are all vulnerable,” said the resident, who is 60. “Who is going to help whom when we no longer know how to access our fields?”

In other areas, such as Kiwanja – one of the largest towns in Rutshuru territory – residents alleged that rebel leaders have appropriated land, depriving smallholder farmers of their main source of livelihood.

Locals believe the land was taken to feed M23 fighters and to generate profit. Several said they saw rebel officers arrive in jeeps to mark out plots before bringing in tractors to start farming activities.

One Kiwanja resident said he had only recently acquired a plot of land for $300. “Before I could even begin to cultivate it, the M23 comes and snatches it away from me,” he said.

The resident, a father of four, said he fears his family will face famine after losing the land. He explained that he had already spent the little money he had saved up preparing the field for the next growing season.

Despite these alleged abuses, few interviewees said they feel willing to speak out given the M23’s intolerance of dissent, and the conditions facing people who are detained or conscripted.

One former detainee in Rutshuru’s main prison said the M23 arrested him on the accusation of belonging to an anti-M23 militia. On the way to the prison, he said one of his fellow detainees was shot dead at point-blank range.

“During our time in prison, we were not allowed to have visits from our loved ones,” he said. “We barely ate a few roasted corn kernels, and the only pharmaceutical product was paracetamol, which was administered to the inmates regardless of their illness.”

UN experts say Rwanda has de facto control over M23 operations, while HRW has concluded that it is an occupying power under international law, making it legally responsible for the abuses committed by the rebels.

The leader of the M23’s political wing, Corneille Nangaa, has rejected “all reports” of human rights abuses, arguing that they are propaganda from the Congolese government in Kinshasa.

Lower taxes, fewer abductions

Some residents pointed to positives under M23 rule, noting that security has improved in certain ways as the group pushed out criminals and rival militias once blamed for crime and kidnappings.

In Kiwanja, for example, some residents described a sharp drop in abductions by armed groups, which they said used to be common in fields and along certain roads.

“For nearly two years, I have been working peacefully in my field in Kasenyi, east of Kiwanja,” said one resident. “I haven’t heard any more about kidnappings in this area.”

“The number of kidnappings has dropped significantly,” added a second resident. “In areas controlled by the M23, you can now move around all night without being bothered, though insecurity remains in some areas.”

The situation is similar in Budapfa, a village to the west of Kiwanja, according to a local farmer who said he can now camp in his field without fear. “The situation is calm here and I haven’t heard of kidnappings for almost two years,” he said.

Kiwanja residents also pointed to reduced taxes for low-income earners as another positive of M23 rule.

The owner of a clothes shop said his monthly income tax has been reduced to 6,000 Congolese francs (around $2), and that other annual payments and business license fees have not been collected.

Still, some residents questioned where their taxes actually go, noting that the money doesn’t seem to fund public services and seems to serve only the rebel group and its officers.

“These taxes only benefit those who joined the movement and who work with this rebellion,” said a civil society activist living in Rutshuru town.

The humanitarian impact

Public services remain absent despite deep humanitarian need in Rutshuru.

The area relies on agriculture, but many farmers are struggling due to scarce rains.

Banks in rebel areas have also been shut by the Kinshasa government in an effort to disrupt the M23, which means currency no longer circulates freely.

The movement of people and goods between rebel-held and government areas has impacted the local economy too.

Falling purchasing power is affecting local medical centres because “residents are no longer able to pay for their care”, said a nurse from Nyamilima.

Nyamilima residents said they are skipping costly doctor visits and prescriptions, instead turning to self-medication with herbs and leaves foraged from fields.

“I don’t go to the health centre or the hospital due to a lack of funds,” said a woman in her 70s from Nyamilima. “When I get sick, I go to the bush here near my home… to make a herbal tea that can treat malaria or headaches.”

A second nurse from Nyamilima said people’s conditions often deteriorate when they rely on plants alone. “These patients arrive at hospitals late, and the consequence is losing their lives,” they said.

A harsh homecoming

The parts of Rutshuru visited by The New Humanitarian have also seen large numbers of people returning back to their homes following long and difficult periods of displacement.

Many had fled to Goma – the largest city in eastern DRC – when the M23 took over their towns and villages, but were forced to return when the rebels seized Goma earlier this year and dismantled camps that were hosting hundreds of thousands of people.

Others have arrived from refugee camps in neighbouring Uganda, where conditions have significantly worsened following the massive cuts to international aid by the US government.

“We only ate once a day, and it was the same meal consisting of rice and beans,” said a woman who recently returned to Nyamilima. “We slept on the ground on a tarpaulin, and when we fell ill, there was no good care. One acquaintance died due to the lack of care.”

Returnees in Nyamilima and surrounding areas described a harsh homecoming, with many finding their belongings looted, fields plundered, and houses damaged by bad weather and neglect.

One man said he is forced to rent because of the state of his house but struggles to pay. “Almost every day, my landlord comes to collect the debt, and sometimes he addresses me with rude words and threatens to evict me,” he said.

Some returnees said they have been forced to work as labourers in the fields of other locals in exchange for small payments. Others said have received support from locals – in the form of food and accommodation– but that the help is limited.

“Some offered us flour, others a bag of salt or a few beans,” said a returnee from Nyamilima. “But it was only for a short time. Then they tell us: ‘Look at the suffering we endure too.’”

A Nyamilima local who never left – even during the worst moments of the conflict – agreed with that analysis: “We may well be in good faith about helping these returnees, but the crisis is hitting everyone.”

This article was first published on The New Humanitarian: