In the hills just outside the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, lies the home of visual artist Evanson Kangethe, along a dirt road. Born in 1961, this somewhat stocky man with a mane of hair that hasn’t seen scissors in a long time, is self-taught. He observes, interprets, and creates, blending both the good and the bad in his work. “The beauty is that everyone is adapting to the growing chaos in Nairobi,” he says. “Although I live more in a fantasy world myself, I’ve captured the changes in the city in my paintings.”

For many years, Kenyan art was difficult to be seen. In the colonial era, African art was suppressed due to the influence of Christian missionaries, who viewed black culture as pagan, primitive, and evil. Lacking formal education, African artists of that time created works related to spirituality. Their art expressed the feelings of their communities, like the wood carvings from the Makonde and Kamba, and the stone sculptures from the Gusii in Western Kenya. From this traditional art, modern and contemporary art developed, showcasing the personal preferences of the artist.

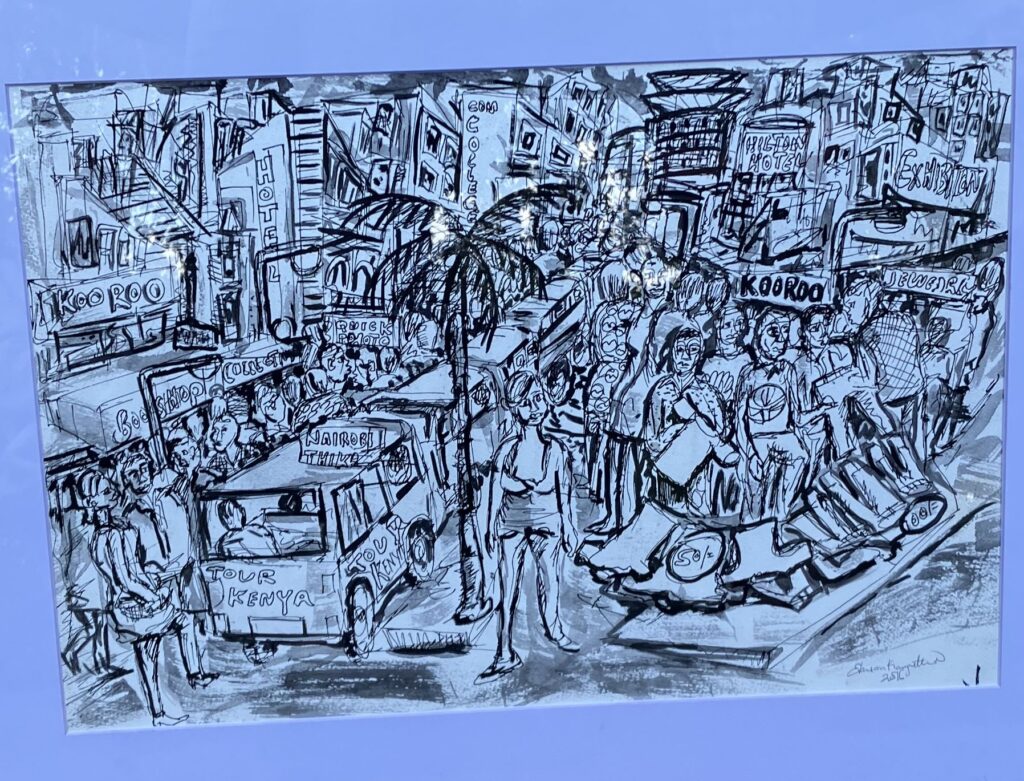

Evanson Kangethe

After gaining independence in 1963, urbanization opened up opportunities for new art: over sixty years, Nairobi transformed from a small settlement where leopards could be found in kitchen cupboards to a bustling city filled with graffiti and heavy traffic. Art galleries and cooperatives began to appear, creating a market for art. In the years following the turn of the century, visual art became increasingly abstract and its themes more political. “The art scene in Kenya is undergoing a metamorphosis,” says gallery owner Hellmuth Rossler. He and his wife, Erica Rossler, will soon publish the book “Echoes of Humanity,” an index of five hundred East African artists and their works exhibited at their Red Hill Art gallery.

Outside the home of artist Evanson Kangethe, in a banana grove, stand his sculptures; inside, in his small studio, his paintings. His view of the streets is the subject of his art, his canvas overflowing with stories. “So much is happening in Nairobi. Look at those market women fleeing with their wares from truncheons,” Kangethe points to one of his paintings. “Look at that drug-addicted beggar with her playing child and the needle in her arm. And over there, that drunken man clinging to a pole. That is the depravity.”

When I ask whether it’s true that he presents the antisocial aspects of urban life in Africa in an appealing way, blending disorder and harmony on one canvas, he agrees with a nod. Kangethe highlights the embellished motorbikes and the sign “Daktari wa Mapenzi,” which means doctors of love, along with a group of men sharing a meal from a single plate. “Isn’t it amazing how market vendors sort their wares on a table? I could stare at those patterns for hours. That’s where the order lies.”

The truth is abstract.

Lemek Sompoika

In contrast to Kangethe’s colorized image of the city is the work of Lemek Sompoika, born in 1988. He grapples with modern life. Sompoika is a descendant of the Maasai pastoralist people. While Kangethe also captures the charm of hectic city life, it eludes Sompoika. “I’ve seen how we’ve become synthetic, like plastic, in the city. City dwellers seem less civilized than those who live in harmony with nature.”

The Maasai man’s spindly legs are still visible in the work, but his face is daubed with an explosion of primary colors, the colors of birds in Maasai land. “I used to depict figures, but over time they became more abstract. It’s like an investigation into truth: the truth is abstract,” says Sompoika at the Kobo Trust, a workshop in Nairobi where a group of artists each have their own studio and exhibit their works in a communal hall.

Lemek Sompoika

Sompoika explores reality through abstraction. As the human figures fade, what is unseen sparks the imagination and encourages us to see things differently, to question reality. His Maasai culture is the starting point. “In the Maasai language, there’s no word for zero, for nothing,” he explains. “And instead of giving an object a word, Maasai describe how the object relates to other things. You suggest things without saying what they are, like in abstract art. It’s not a door, but the mouth of a house. The imagination is still open.”

The shift away from the community spirit of the past to the rise of an anonymous consumer society over the last fifty years was sudden. It continues to create tension. “Is modernity my identity?” Sompoika ponders. “Our parents didn’t worry about their roots. But my generation is looking back to ancient cultures to shape our identity. I express that through art,” he explains. The heart of traditional Maasai culture is the ol-sutwa, which signifies umbilical cord, friendship, and peace. This communal way of living directly conflicts with the individualism found in modern society, especially in the urban mix of 42 ethnic groups in Kenya, each possessing its own language, history, and culture. “The major challenge for modern Africa is to accept that diversity while honoring everyone’s roots. Maybe then we will engage more socially,” says Sompoika.

Lemek Sompoika

Surrealist Landscape

The feeling of community in rural Africa, along with the strong connection between people and animals, like that of the Maasai, goes back to well before independence, when most Kenyans had little contact with the outside world. Hellmuth Rossler regards Kivuthi Mbuno, who was born in 1947, as a trailblazer of modern art in East Africa. He learned to paint on his own: while working as a cook during hunting safaris in the bush, he painted what he saw in a very figurative style, featuring many animals but set in a surreal landscape.

Joel Oswaggo, born in 1944, is another key figure among Kenya’s self-taught artists. He painted relatively factual village life in harmony with its surroundings. His work is realistically figurative, depicting poverty but making no political statement. The political explosion only occurred after the turn of the century.

Joel Oswaggo

The monotony of the stifling one-party state was then overhauled, creating space for liberal ideas. Politics then permeated art, and more abstract paintings emerged. Like Justus Kyalo’s painting on red canvas, full of lines that protrude outward. Or an expressionist-style painting by Samuel Ashanti Githinji, with the image of a skull with people emerging from it, a bitter political satire on the theme: now it’s our turn to eat. He transforms grieving human figures into beasts, emphasizing the harsh reality of hatred and violence. His paintings often feature dramatic cuts, which are sewn back together to symbolize reconciliation.

Peterson Kamwathi

Africa has, in a way, become bleaker over the last fifty years, plagued by toxic corruption and oppressive politics, while the optimism of the post-independence era has faded into history. For visual artist Peterson Kamwathi, the face mask represents the harsh realities of the new century. “The face mask, as a way to conceal your identity,” he states firmly. He observed it among migrants heading to Europe, wearing face masks to guard against the sun and sand of the desert, just as urban residents donned masks to protect themselves from pollution and Covid. They used masks to shield themselves from tear gas deployed by police and surveillance cameras from secret services. Kamwathi employed charcoal in a dark painting to illustrate politicians with their faces covered by pages from the constitution, following the violent unrest in Kenya in 2008 caused by electoral fraud.

Peterson Kamwathi

Born in Nairobi in 1980, Kamwathi is gentle and sharp. In his studio at the Godown art center, his thoughts dart in many directions, just like in his paintings, without losing sight of the bigger picture. “I’m not a political activist, certainly not. But politics is everywhere; as an artist, you can’t ignore it,” he says.

He unfurls a canvas from the Noble Savage series. His series, featuring generic, block-shaped figures in the foreground, explore themes of personal identity and how the individual is inextricably linked to the collective. With the anti-colonial struggle increasingly in the rearview mirror, Kamwathi represents the generation of East African artists inspired by current social, cultural, and economic issues. “I am a product of this century.” His work is rich in symbolism, with conceptual elements that offer visual insight into the realities of everyday life. “I strive to address and document the issues that affect my country, my continent, and now the planet.”

Peterson Kamwathi

Generation Z

At the same time, a new era is beginning: Generation Z. This generation has moved away from the traditions of obeying their elders and politicians over the past year. Their style is both raw and meaningful, and their approaches are serious yet humorous, filled with sharp memes and sketches. These contemporary keyboard warriors are targeting not just a haughty political class but also their parents, who have long accepted a submissive role due to tribal customs. That unquestioned respect for elders has now disappeared.

This refreshing perspective reflects another social metamorphosis. “The future is based on the stories we tell,” says Sompoika. “Generation Z has a different narrative; it feels like something new is coming.” And Kamwathi: “Let young people engage in this revolt. I expect a new wave of expression from young Gen Z artists. Their paintings will contain an organic rawness.”

This article was first published in NRC on 17-7-2025