Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Sudan is undergoing a war of destruction, with not only a humanitarian crisis and destruction of infrastructure, but also the historical works of art in danger. “Our cultural heritage is in danger of being lost. The National Museum in the capital Khartoum has been attacked in recent weeks. Militiamen broke old pots and opened caskets with mummies,” says Elnour Hamir from his place of exile in Paris. Since the fall in 2019 of former president and autocrat Omar al-Bashir, he has been head of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), which was established for the preservation of Sudan’s cultural heritage.

In April, two factions of the military plunged Sudan into a brutal power struggle: President of Sudan Sovereignty Council Abdel Fattah al-Burhan’s regular forces and that of the Rapid Support Forces. The RSF is a paramilitary force led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, a militia from the desert in western Sudan that was incorporated into the National Armed Forces. The fighting is concentrated in Khartoum and the Darfur region. The fighters of Hemedti operate in the streets with light weapons on their pick-ups, the army of Burhan hits them with heavy weapons, with fighter jets and drones.

Hemedti’s RSF fighters used the scorched earth strategy in the 2003 war in Darfur. They now fight in the cities with the same attitude: for them the state is a booty and the population a target to rape and rob. They occupy homes, hospitals, schools, and value museums.

“We have forty employees in Khartoum to assess the damage, but they can only leave their homes during the short ceasefires,” says from Barcelona Isber Sabrine, head of Heritage for Peace; an international NGO that tries to protect cultural heritage in war situations.

“They behave like barbarians,” says Elnour from Paris about the RSF soldiers who entered the National Museum of Sudan in Khartoum. When they opened containers with ancient mummies, they proclaimed on social media that they had discovered victims of al-Bashir’s rule. “They are undeveloped, they have no idea of culture and history,” says Elnour. All museum guards have since fled.

According to UNESCO; the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, the archives of Ahlia University in Omdurman also suffered significant damage. Thousands of old books and rare documents were lost in a fire in the university library.

Blue Nile

In the words of ancient Egyptian priests, in the Nile “floated in the bottomless water the seed of all things.” Sudan’s cultural history centers around the Nile, where great empires arose. In the capital Khartoum, the most important museums are located on the riverbank.

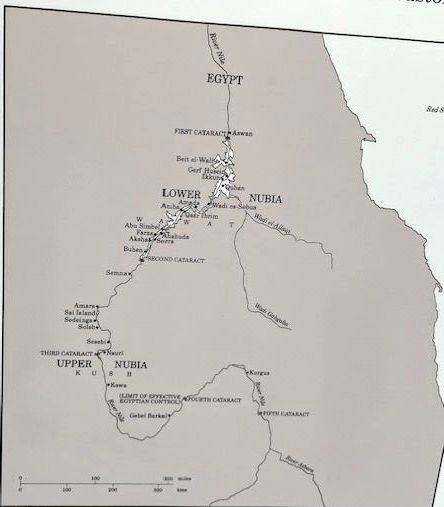

Sudan is home to two hundred pyramids and has the largest collection of historical cultural treasures on the continent after Egypt. This is partly due to the excavations in the region where in ancient times the legendary Nubian empire of Kush was located, an early black African nation-state with its own script, industry, arts and sciences. The area is located north of Khartoum near several waterfalls in the Nile.

So much of this culture was preserved because of the construction of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt between 1960 and 1970, which flooded the Nile basin for a distance of 500 kilometers. Archaeologists went busily to work at that time to find and save statues and temples. According to information from the British Museum, which houses a statue of King Anlamani and many other artifacts of Nubian culture, “these rescues resulted in this area probably providing archaeologists with the most thorough documentation of any comparable area in the world.”

The Blue Nile flows in front of the National Museum of Sudan, which houses more than 100,000 objects from Sudanese history. It houses the world’s largest Nubian archaeological collection, such as the granite statue of the king Taharqa, ruler between 690 and 664 BC. Four of the rebuilt Nubian temples are displayed in the museum garden. There are also statues, mummies, and murals from the Stone Age. By a happy coincidence, most of the art pieces were put away some time ago due to a renovation. But being in the middle of the front line, the collection in the garden is in danger of being hit.

Across the bridge of the White Nile, less than three kilometers west of the museum, lies Omdurman, the ancient capital of Sudan. Here lies the tomb of the Mahdi, who established a state in Sudan in the 19th century after a revolt against the British and Turkish occupiers. Also, there is a new museum recently opened in the former home of Khalifa Abdullah ibn Mohammed, who ruled Sudan before being defeated by the British in 1898. In both places the RSF set up a military base and therefore they can become targets of airstrikes or bombings.

Arab merchants

Those who dare to walk east from the National Museum through a neighborhood with many snipers present will arrive at the old and new presidential palaces, both damaged by the fighting. A stone’s throw away is the Ethnographic Museum, where the diversity of Sudan is shown. Sudan is a multicultural country. For hundreds of years since the 7th century, Arab traders traveled south through the Sahara, across the Red Sea and down the Nile, taking their Islamic faith and culture with them.

“In the Ethnographic Museum, we show the diversity of all ethnic groups in Sudan today, of their cultures and traditions, with fascinating statues, masks, jewelry and beadwork of both African and Arab origin,” says Elnour of the Sudanese heritage organization NCAM. “With this collection we want to contribute to solving Sudan’s identity crisis. An elite of Arab or Arabized rulers has always wanted to mold the country into an Islamic Arab state. But we Sudanese are much more diverse, and this museum is proof of that.”

As part of the campaign to show all faces of Sudan, Elnour helped to set up such ethnological museums in Darfur, in Al-Fashir, Nyala and El Geneina, cities where, like Khartoum, a battle of destruction is now taking place. However, many of these new museums had not yet opened their doors when the war began.

The RSF are robbers, not iconoclasts, like the Taliban in Afghanistan back then. “But the RSF do commit crimes for which they can be prosecuted, because the destruction of national heritage is internationally considered as a crime,” warns Isber Sabrine of Heritage for Peace.

NCAM’s Elnour is not yet concerned about art thieves, such as the theft during the war in Syria. However, he fears “the madness of gold”. In the unflooded areas of the Kush empire, pyramids and temples are located in remote places. “Many Sudanese mistakenly suspect that gold is hidden under the pyramids,” he says. “But fortunately these antiquities are protected; since the beginning of the war, local residents have taken up surveillance”. That gives a little bit of hope in these dark days for Sudan.

For more info on the destruction see: https://www.heritageforpeace.org/sudan-reports/

This article was first published in NRC on 27-6-222023