Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

The girls from Butere Secondary School were overwhelmed by a choking haze of tear gas. It happened in early April in the town of Nakuru, during Kenya’s national drama festival. Their play, Echoes of War, tells the story of Gen Z youth rising up against corruption and misrule under a fictional regime – but no Kenyan could fail to notice the connection to the rule of President William Ruto, under which dozens of young people have been disappeared or murdered. First, the authorities had banned Echoes of War, but a judge later reversed that decision, and then the police brutally stopped the performance all the same.

History repeated itself once again. In 1977, fourteen years post-independence, the police destroyed a village theater for having the audacity to perform the play Ngaahika Ndeenda (‘I’ll marry when I want to’) by the famous Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong’o. The drama is about how the ideals of the anti-colonial struggle were squandered by Africa’s rulers after independence.

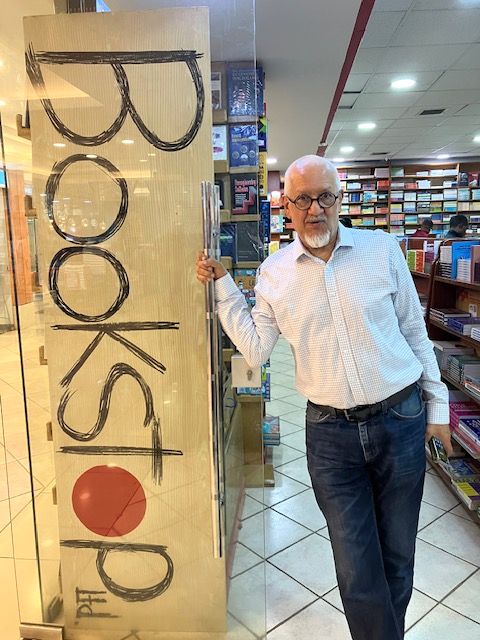

“You would think that such censorship is a thing of the past in Kenya,” grumbles Chan Bahal, owner of Bookstop, considered the best bookshop in East and Southern Africa, in Nairobi. “How absurd that we still have to face this kind of intimidation by government idiots.”

Bahal first came into conflict with censorship himself in 1987. He can still chuckle about it. “It was about Playboy.” Of course, critical people like me didn’t listen to the only radio station at the time, the state-run one, and so I missed the news around lunchtime that Playboy had been banned. Within an hour, ‘the men in black’ showed up at my shop and secret agents took me to the station. That was the first case against me.”

Handful of bookshops

We crossed paths back in the early 1980s. During that period, the editor-in-chief of the biggest newspaper in the country, the Daily Nation, would bring a toothbrush to work every day, as there was a solid chance he might end up spending the night in a cell due to an article that upset then-president Daniel arap Moi. The city had just a few bookshops, mostly serving tourists looking for ‘exotic’ literature about Africa.

Chan Bahal owned the stationery and bookshop Momentos in Nairobi’s Westlands area. I handed him Africa Confidential, a British newsletter that comes out every two weeks, covering politics and economics in Africa. It was banned in Kenya, but he was keen to make copies for his customers. He sold me a prohibited book – like Petals of Blood and other works by Ngugi wa Thiong’o – which I took home in a brown paper bag.

In the late 1990s, he relocated to Yaya, one of the first shopping malls in Nairobi, and opened Bookstop. Chan Bahal hasn’t changed much since then: he still engages with customers about books with the same passion, reading excerpts aloud, still as talkative and articulate as ever – at Bookstop you can’t get away with a short visit.

Selling from the trunk

Kenya modernized rapidly after the turn of the century and grew from a garden city to a metropolis with more room for free spirits. With a growing group of well-educated young people, the arrival of satellite television and later the internet, censorship seemed to be a thing of the past. But the leaders still want to control the thoughts of the population.

Bahal started to stand out in the posh shopping mall and that brought risks with it. He sold little-known but controversial books from the trunk of his car in the parking garage. But other, more popular books were in such high demand that it became difficult to sell them under the counter. He was caught and came into serious conflict with the Kenyan government, in particular with the most feared man of the Moi regime: his all-powerful right-hand man Nicholas Biwott.

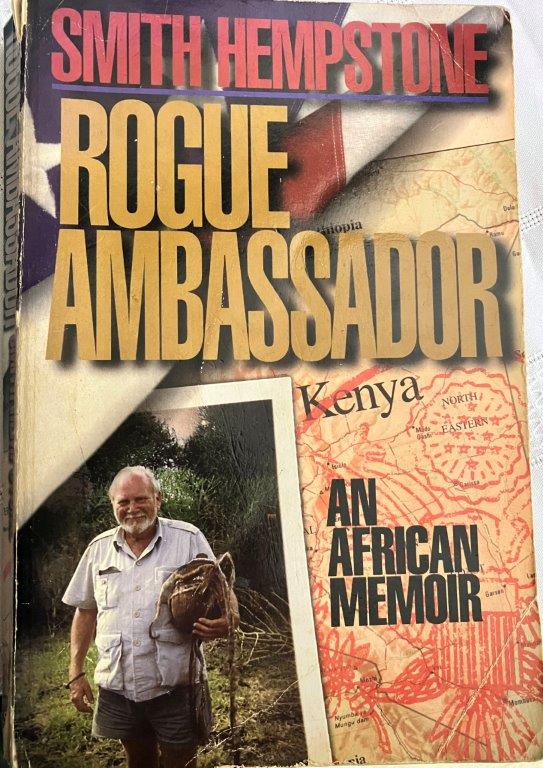

Every Kenyan was scared of the guy known as ‘Total Man’, who had a reputation for being corrupt and violent. In 1990, his rival, Minister Robert Ouko, was killed. American ambassador Smith Hempstone pointed the finger at Biwott in his book Rogue Ambassador. With public pressure mounting, Moi brought in Scotland Yard to look into the murder; even though the president tried to block the investigation, it still resulted in a report that implicated members of Moi’s inner circle. A British supermarket owner also linked Biwott to the mysterious murder of his daughter in Kenya in his book. It’s worth noting for Chan Bahal that Biwott owned Yaya, making him the landlord. “That was extra scary.”

Shady characters

Because Bahal sold the books in which Biwott was described as a murderer, he was considered an accomplice. Biwott also started a lawsuit against the respected NRC in the Netherlands because the newspaper had described him as corrupt, a case that was dropped. From Bahal Biwott demanded damages and an apology in an advertisement in the newspapers. “I think we ended up somewhere around five million Kenyan shillings [about 60,000 euros at the time]. I was broke.”

Shady characters kept asking for the book, he says. “I would have been stupid to say yes. They were trying me out. In the meantime I had learned how to deal with these secret agents. And of course I feared revenge from the murderers.”

Bahal often tells me to switch off the tape recorder. Then he brings up a politician who had someone killed, and after that, the murder case just goes cold. The fear from years of book censorship has really sunk in. “I am more afraid than I used to be. Isn’t there a sensational murder every week? Or they throw corpses in rivers. Every day there is a new law, every day they scare us. If a book about that were to be published, I would think twice before offering it for sale. The younger generation of activists or politicians can express themselves in public, as a group they are strong. As a bookseller I am on my own. The authorities still want to control what we read, what we say, what we do.”

Bahal often has to gauge how a book will be perceived by the political elite or a very volatile president. He navigates the gray area between what can be done openly and what needs to be kept under wraps. Take The Constant Gardener by John le Carré, for instance, which paints a vivid picture of corruption in Kenya. Or consider It Is Our Turn to Eat by Michela Wrong, which reveals how millions of euros went missing. “That book is too hot to sell,” he mentioned in an interview with the Daily Nation, yet he ended up selling it discreetly. Due to the high demand, he simply placed it on the counter.

Hemingway

His bookshop grew into an institution, with the non-fiction section in particular being praised by well-educated Africans, foreign diplomats and aid workers. People travel from all over the eastern and southern parts of the continent to his Bookstop for these academic books. He calls them “security books”, specialized literature about conflicts in the Horn of Africa, for example. One day, former South African President Thabo Mbeki came to see him. “He called me a true son of Africa, because of the books I sell. He bought for between 200,000 and 300,000 shillings (about 2,000 euros), and his bodyguards were also allowed to choose a book.”

One can find other insightful reads in the Africana section, especially history books about Kenya. Back in the day, bookstores were filled with bestsellers aimed at tourists, like those by Ernest Hemingway or his peer Robert Ruark, who traveled to Kenya for hunting. These books, penned from a Western viewpoint during colonial times, painted a romantic picture of Africa: sitting by the campfire with a drink, surrounded by dancing Maasai, with Hemingway’s The Snows of Kilimanjaro resting in the tent beside the camp bed. These authors were primarily captivated by wild animals and the thrill of killing them. They rarely wrote about Africans themselves. However, censorship was present even back then: Ruark had to leave the country in 1962 due to backlash against his book Uhuru (Freedom).

Hidden history

These days, Kenyans are uncovering their own past instead of the one dictated by colonial powers. Bahal says, “We have a hidden history. There’s still so much more to share.” Writers like Peter Kimani are now telling that story from the viewpoint of the fight against the colonizers. For instance, there’s a book about Dedan Kimathi, who led the Mau Mau resistance against colonial rule. “When young Kenyans see their grandfather’s name pop up in that book, it’s like, wow, they get super excited!”

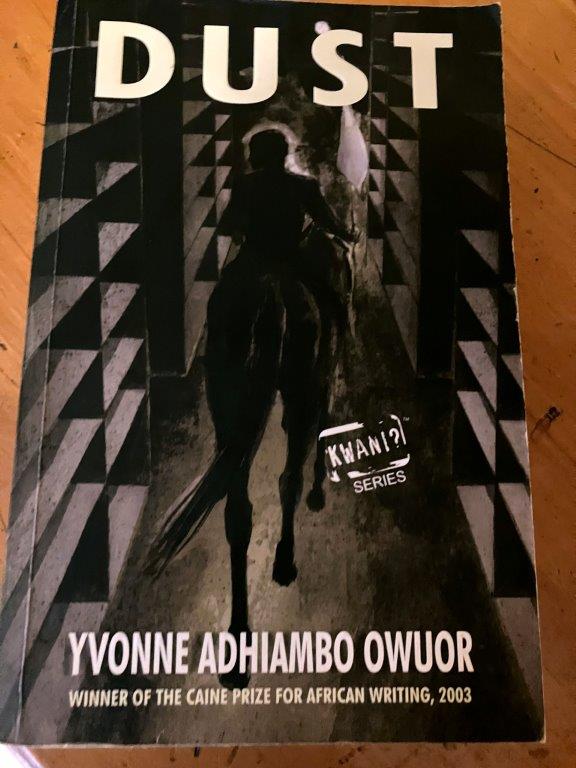

He was a champion for Kenyan literature 22 years back when the first literary magazine, Kwani?, was launched by Binyavanga Wainaina, who also wrote How to Write About Africa, a sharp critique of how foreign journalists report on Africa. Bahal has been inviting young writers to book events and has played a key role in launching new authors like Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor and Peter Kimani.

At the counter is Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, the best-selling book of the week. And he also has an eye for the aspiring reader. He set up a TikTok section, with titles such as Not in Love and A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder. “How many mothers come here to complain about their children glued to their smartphones? Then I take these children aside and read a passage from a book. You have to read with love and then such a child says: ‘Wow, that man sounds sweet when he reads. I want that book.’ You have to make that personal contact. It takes time.”

Bahal emphasizes that he is a businessman, but he also does his work out of idealism, he says. Anyone who wants to understand something about Africa and wants to read about it will definitely end up with him. “You want to spread the gospel, you know? You try to become a little bit famous among a group of people. I did it, I sold you this book. I am a good person.”

He is in his Bookstop from nine to seven, seven days a week. “I have now lost 60 percent of my vision and reading hurts me. But I want to read everything. I have to read, otherwise I can’t sleep. I still put a book under my pillow.”

This article was first published in NRC on 5-7-2025