Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

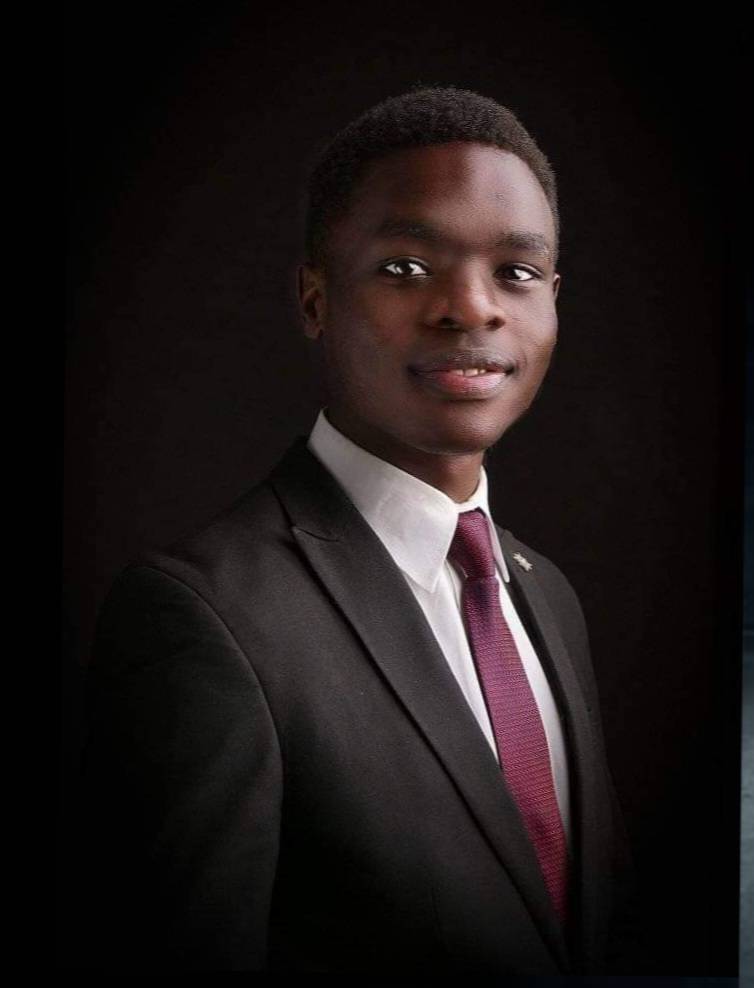

Boniface Mwangi, a major person in the Gen Z movement, is kidnapped today, Sunday 27th of October. He is released day after the arrest without being charged.

Joshua Okayo (28) was devastated. After his kidnapping by the Kenyan police last July, the young Kenyan had for three days a gunny sack placed over his head. With his hands in cuffs, his entire body was subjected to hours of torture. The beatings were so severe that his “senses no longer worked,” he says. “It drives you crazy when you are beaten but you cannot deflect the blows because you do not know from which direction they are coming. I surrendered. Because the enemy was stronger. All I could think about was whether my parents would be proud of me now that I was dying.”

Student leader Okayo is a key figure in a widespread social uprising among Generation Z in Kenya, generation born between 1995 and 2010. In July, he was arrested following a large-scale protest against President William Ruto’s severe austerity measures, during which demonstrators breached the parliament and forced Members of Parliament to flee through an emergency exit. After being detained for several days, he was subsequently released by being thrown from a moving vehicle.

The Kenyan police regularly kidnap political activists in an attempt to silence the youth revolt. According to the government, 42 protesters were killed during the protests, while human rights groups say 61 were killed and 67 were kidnapped. Another one of them is Bob Njagi. Last month, masked plainclothes officers dragged him from a public transport bus just outside the Kenyan capital Nairobi and pushed him into a car with no license plate. After a month in solitary confinement, they dumped Njagi far from his home on the side of a road and warned him: “You will be killed if you reveal anything about your ordeal.” So Kamanda Mucheke of the Kenyan Commission for Human Rights spoke for him: “Njagi is deeply traumatized after a month of terror and severe physical and mental torture. He was kept isolated from other prisoners, naked all the time, chained to a metal hook fixed to the floor of the cell.”

Njagi’s disappearance received heightened coverage in the Kenyan media. The Law Society of Kenya (LSK) intensified the pressure by utilizing the judicial system to compel the police to reveal his location. Lawrence Mugambi, the High Court judge overseeing the matter, summoned Gilbert Masengeli, the acting police chief, to provide an explanation regarding Njagi’s disappearance. However, the police chief disregarded the summons, leading the judge to impose a six-month prison sentence on him. In retaliation, the police chief withdrew the police protection assigned to the judge and his driver, an action that was later characterized by Kenya’s Chief Justice Martha Koome as a ‘direct assault on the independence of the judiciary.’

This war of words between the various arms of the government apparatus led to the release of Bob Njagi and the judge withdrawing his arrest warrant against the police commissioner, after which the commissioner gave the judge his security back. Although Kenya is considered one of the freer countries in the East African region, the saga surrounding Njagi’s disappearance raises the question of who calls the shots in Kenya: the judges, the politicians or the security apparatus? In other words, is Kenya a democracy or a police state? Kenyan journalist Macharia Gaitho, who was himself abducted by plainclothes officers in August, comes to a stark conclusion in his column in the Daily Nation. “Kenyans are being sucked down a dark, dangerous path of kidnappings, torture, killings, secret prisons and other activities that herald a return to the police state.”

Joseph Kariuki Mwangi, spokesperson for the NGO International Justice Mission, also comes to the same gloomy conclusion. “The government’s intolerance of critical voices is growing. Politicians are using the police to combat opposition. The level of democracy is deteriorating. Kenya is struggling with the arrogance of those in power,” he judges. In line with Okayo’s testimony, human rights organizations, which at the time strongly criticized the suppression of the demonstrations, speak of the return of the torture chambers. Several demonstrators told in July how their demonstrations were disrupted by government infiltrators. In addition, police units are said to have attacked medics who were taking care of injured demonstrators.

The repression and suppression of political dissent have a long history in Kenya. Since gaining independence in 1964, the nation has faced significant violations of human rights, regardless of whether it was under democratic or authoritarian rule, particularly at the hands of the police and intelligence services. Many individuals responsible for political assassinations have never been brought to justice. The Kenyan populace has made efforts to compel members of the security forces to provide transparency. When parliament opened an inquiry after the murder of critical MP Josiah Mwangi Kariuki, popularly known as JM in 1975, the head of the secret service appeared before the parliamentary committee and thundered to the people’s representatives: “I can arrest some of you as soon as this committee has finished its work.” Another high-ranking security officer appeared before the committee armed with a pistol. Although Kariuki’s murder was never solved, it is believed that it was carried out on the orders of former president Jomo Kenyatta (1964-1978).

Under his successor Daniel arap Moi (1978-2002), Kenya degenerated into an autocratic police state. Although Kenyans placed their hopes in his successor Mwai Kibaki (2002-2013) to restore democracy, the culture of impunity under repressive police authorities and political assassinations of dissidents did not end. Recent months have also shown that current President Ruto, despite his repeated promises, is not working to create a safe political culture.

Is Gen Z in retreat?

Although the loud voice of Gen Z, which heralded the new wave of repression, is widely seen as refreshing, some Kenyans also see the youth as naïve. They are said to underestimate the power of their opponent to strike back. Where dissidents used to act cautiously out of fear of the police and voice their criticism more subtly, Gen Z youth are much more reckless in their outrage. Kenyan youth feel that they have the right on their side in standing up to corruption and other abuses of power. The spontaneous mass demonstrations in July created unity and self-confidence, but the series of disappearances and kidnappings that followed is forcing some of the young dissidents to act more cautiously.

The kidnapped Joshua Okayo is living proof that political resistance by the emerging Generation Z has a price, but has not been wiped out by police violence. The student leader is one of the few who continues to speak out openly. “We have set up a political party,” he says proudly. “If all the young people vote for us in the elections, we will take power and I will become president of Kenya.“

Death penalty

The rule of law is also under pressure in many other African countries as a result of governments’ concerns about the growing Generation Z. While relatively democratic Kenya is falling back on old methods to break the resistance, neighboring countries Tanzania and Uganda had already taken measures against the young people and opponents before they could take to the streets en masse.

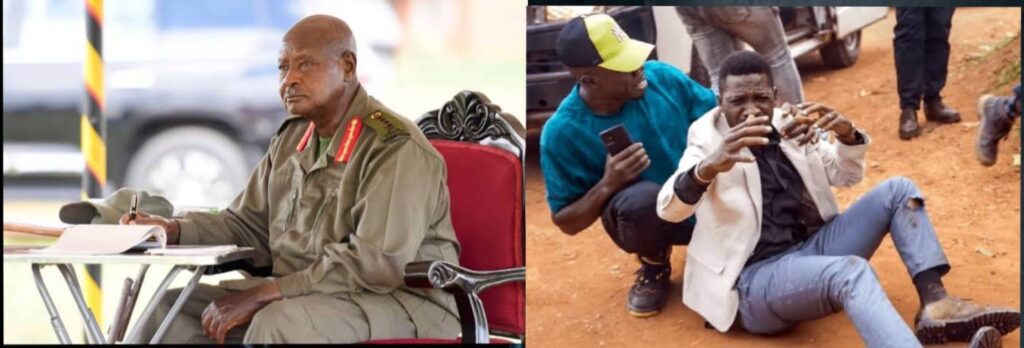

On the eve of a demonstration in Tanzania against the government of President Samia Saulu Hassan, opposition leaders and journalists were arrested. In September, intelligence operatives forcibly removed opposition leader Ali Mohamed Kibao from a public bus, and he was found dead a few hours later, with his face burned by a chemical substance. “It is clear that we have become a police state without any legality or legitimacy,” wrote respected Tanzanian columnist and lawyer Jenerali Ulimwengu on X. Uganda is widely recognized for its issues related to police brutality. The aging military leader, Yoweri Museveni, swiftly retaliates against any critical voice. Recently, a tear gas canister discharged by law enforcement struck musician and opposition figure Bobi Wine in the leg, marking yet another attempt on his life. In Nigeria, ten protesters from Generation Z have been accused of high treason, a charge which carries a possible death penalty.

This article was first published by the NRC