Prison conditions in Kenya are inhumane, and in particular in Makadara remand. How can a reasonably developed country treat prisoners as if they have no rights?

You wouldn’t wish even your worst enemy to end up in a Kenyan prison. “Everything is bad there. Everything is hell. From what you eat to the toilet you use,” says Timothy* who has just been released.

Willy Mutunga (77) confirms the poor conditions, and in particular those for pre-trial detainees who wait years for their trial, like in Makadara. Mutunga is a former political prisoner and later became president of the Kenyan Supreme Court. “It is inhumane,” he says about the infamous Makadara prison, where he himself stayed in the early 1980s before he was appointed head of the judiciary in 2011.

The prison from 1911 was built for two thousand prisoners, currently 4,317 people are locked up there. The detention center is located in the industrial area of Nairobi, behind a high wall and barbed wire. Timothy, a shepherd hailing from the vast plains of northern Kenya, possesses little formal education and previously held the position of a night watchman for a construction company in the capital. He found himself incarcerated in Makadara for a duration of one year. According to him, in 2023, at around three o’clock in the morning, a group of criminals arrived. However, Timothy was fast asleep and remained oblivious to their activities as they absconded with heavy machinery and a trailer. Upon awakening and discovering the theft, he fled in a state of panic. Subsequently, on the same day, law enforcement apprehended him and levied charges of theft against him.

*Timothy

The government assigned him a lawyer. “At first he wanted a bribe of 1000 euros, with which he would bribe the judge,” says Timothy. “But I’ve never had those kinds of amounts.” His lawyer advised him to plead guilty in exchange for a reduced sentence. “If I didn’t do that, I would have to wait many years in pre-trial detention for my verdict. My trial lasted less than half an hour and no witnesses were called.”

Former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga confirms that many innocent people agree to a plea bargain – initiated by the defense counsel, or the prosecutor, or the magistrate – and declare themselves guilty for a reduced sentence or a fine. “Otherwise you might have to wait seven years for your case to be heard,” he says. “For people in pretrial detention, prison is a blatant subversion of the mantra that we are innocent until proven guilty.

Elite treatment

Michael* is a chaplain. A few years ago he started training to become a priest, but he soon chose fighting social injustice over speaking from the pulpit. He visits prisons every week. “The government lawyers are only in it for the money,” he grumbles. “They promise everything, take the bribe and then you never hear from them again. Many are innocent, but because there is such a backlog in processing cases, they languish in the hell of Makadara. Animals in a cage live a better life.”

Timothy was wearing plastic sandals without socks on the day of his arrest. He was wearing old pants without underwear. That’s how he went to prison, that’s how he got out a year later. “I have never worn any other clothes in all that time, because you don’t get those in Makadara.”

Crammed with more than a hundred others, he was in a cell for suspects of theft and sexual abuse. “I made my place to sleep on the floor, without a mattress, without a mat, on the cement floor, right next to a neighbor, with my back turned to him.” Just like outside the prison walls, not everyone was equal. “The rich slept in what we called the presidential palace: they had a mattress and they were allowed to watch television.”

Willy Mutunga says that such a ‘state house’ behind bars dates back to colonial times. Prisons were segregated and the ‘state house’ was reserved for white inmates. “Makadara prison, like all other detention centers in Kenya, was built under colonialism. There used to be such special treatment for the elite, at the time for the white colonials, they did receive bed linen.”

Ordinary prisoners have to make do without soap and toilet paper. “If I hadn’t brought toilet paper and soap, Timothy would never have been able to clean his butt,” says chaplain Michael with a Mona Lisa smile. “I also never forget to take cleaning supplies for the toilet with me, the smell of urine is unbearable.”

Extra clothes are not allowed, so if you want to wash the clothes on your body, you make a deal with another prisoner. Timothy: “We both took off our clothes, I put on his and went to wash mine. Without detergent. As compensation, I had to wash his clothes later.”

Screaming cats

The daily routine in Makadara is a cup of weak porridge for breakfast at seven o’clock, poorly cooked cornmeal and spinach water at eleven o’clock and dinner with a plate of beans at three o’clock. “Because it was so little, you could approach the server to ask for more,” Timothy continues. “Or you asked for something extra at the state house. But you had to pay a price for that: you sold your ass for an extra bite.” Chaplain Michael provides psychological help to prisoners. “The first problem they raise is that they have been assaulted. There is so much sexual violence happening,” he says.

Sometimes in the night there would be a howling sound, like that of warring cats. That scared Timothy. “We thought someone would die the next morning.” That was often the case. “If you had a headache, you were given a tablet for worms in your stomach. Sick prisoners died regularly.”

How do you survive in a world without windows, without fresh air, without news from outside? Timothy has lost a lot of weight, his skin is dull and gray. “Sometimes I prayed to God to come and get me, and then I lost all courage. Often I just wanted to be dead.” A year later he was back on the streets – like a zombie, unable to blend in with the crowd. “I was sweating like an ox and my legs were shaking.” Chaplain Michael: “After their release, some can no longer talk, they are completely disoriented. Their minds seem deleted. And when they recover, they often become hardcore criminals because of their experiences in Makadara.”

Why does a reasonably democratic country like Kenya treat its prisoners in Makadara as if revenge is being taken on them, as if they no longer belong to a country with rights and values? Chaplain Michael shrugs. “When I raise this with the director of Makadara, he complains about insufficient resources for a good diet and hygiene.”

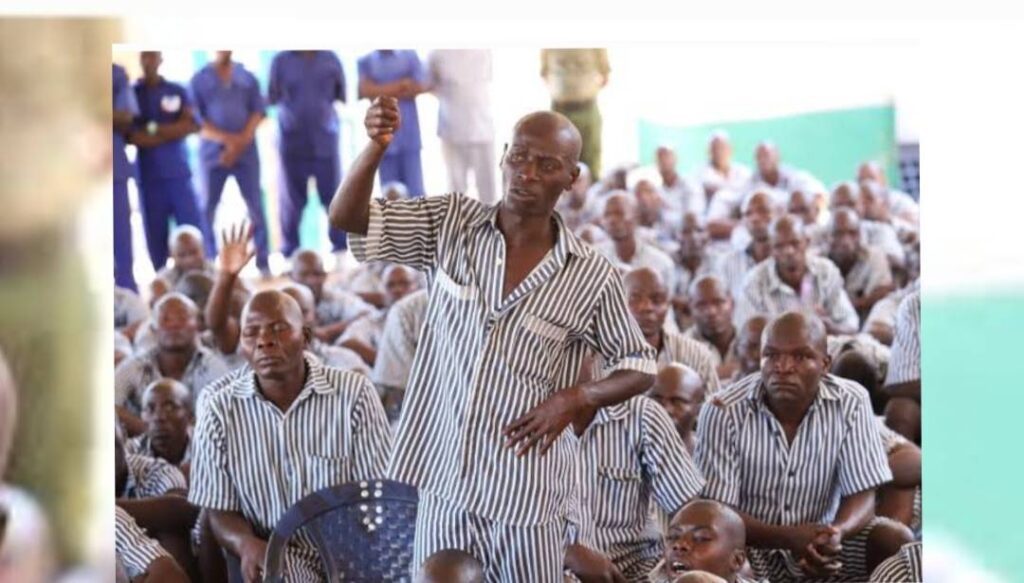

Zebra uniform

During the reign of autocrat Daniel arap Moi (1978-2002), torture occurred and numerous detainees died, as stated in a 1999 Amnesty International report. Following Moi’s exit, the subsequent administration initiated reforms, spearheaded by former Vice President Moody Awori (2003-2008). “Prisoners are people, people who need to be rehabilitated. They are not scum, deprived of any claim to human rights and love,” he said.

Following a conviction, inmates often desire the zebra uniform as it grants them the opportunity to participate in supervised public works beyond the prison confines. This enables them to supplement their income. However, with the exit of Moody Awori, progress in such initiatives has halted, leading to a stagnation in the development of the prison system in Kenya and across many African countries.

Willy Mutunga is now retired and is still a human rights activist. “The situation in prisons reflects the inhumanity of our society,” he said. “They should be abolished.”

* The names mentioned are not real

This article was first published in the Dutch daily newspaper NRC on 24-6-2024