By Adior Ibrahim

This story was originally published by The New Humanitarian: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/first-person/2023/10/10/flipping-narrative-how-id-card-shapes-refugees-life

Have you ever stopped to think how the identity card you carry in your pocket determines how much control you have over your future?

When I imagine my future, I picture myself working my dream job as a developmental psychologist, being able to travel with ease, and not living in fear of being detained or threatened with deportation because of my status as a refugee.

But from the moment people become refugees, the reality is that they have very little say in what happens next in their lives.

Instead, we are made to depend on aid, and we encounter numerous challenges when trying to make choices about our lives and our futures. Many of these challenges stem from issues related to the IDs and documents that establish people’s legal status in the world, which we either don’t have or struggle to obtain.

For example, I was born in no man’s land while my family was fleeing the civil war in South Sudan. Like many other South Sudanese refugees around my age, I do not have a birth certificate. My mother did not have access to a health facility when she gave birth, so registering my birth and obtaining documentation was not possible.

Instead, three hours after I was born, I was bundled into a sling made of an empty food sack, and my family and the group of people they were travelling with continued their journey toward safety.

To this day, the birthday the UN’s refugee agency (UNHCR) recorded after we arrived in Kakuma camp in Kenya in 1997 is a different year and month than the day my mother actually gave birth. And even after arriving in Kakuma, it took three years for my family to be officially registered as refugees by UNHCR and to receive refugee ID cards.

It didn’t take long for my mother to realise that the camp provided little to no opportunities. Refugees were left with the choice to either stay in the camp and struggle to get by with bare minimum social assistance from UNHCR or go to the city to pursue the dream of being self-sustaining.

In the camp, you feel your power to uplift yourself has been taken away, while you depend on organisations to give you crumbs of support. But having a refugee ID doesn’t allow you to travel and live in other parts of Kenya unless you apply for permission from the government, which is a long and complicated process. So leaving the camp is difficult unless you make the decision to become undocumented.

‘We were undocumented’

When I was young, I developed a severe illness and needed to travel to the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, for medical care – a process UNHCR facilitated by obtaining travel permits and covering the cost of hospital bills.

During one of the trips to Nairobi in 2003, my mother resolved to stay in the city because she realised there was no future for my three siblings and me in the camp. Staying in the city would give us the opportunity to get a primary education, and she would be able to work to support herself.

What we didn’t foresee were the implications of her decision years later, when I turned 18. Because we hadn’t returned to Kakuma, our refugee status became inactive, which meant we were undocumented. After I completed high school, I wanted to continue my studies, but I needed an ID card – which I didn’t have – to be able to apply for university and for financial aid.

For seven years, I tried to trace down my refugee registration in Kakuma from Nairobi, but UNHCR kept telling me to return to the camp.

Eventually, I was able to enrol in a private university that understood my situation, but this is not a solution that is available to many refugees. I had also learned the difficulty and limitations of living in Nairobi undocumented and wanted to try to regularise my status.

For seven years, I tried to trace down my refugee registration in Kakuma from Nairobi, but UNHCR kept telling me to return to the camp. Finally, last year I was able to return to the camp and initiate the process to reactivate my status and transfer my registration to Nairobi so I would no longer be undocumented. It has been more than a year now, and the process is still pending.

‘Even refugees should have control over their own futures’

For most people, being issued a birth certificate and getting an identity card aren’t even things they have to think about. Those two documents allow you to attend school, access health services, set up bank accounts, register telephone numbers, obtain work permits, and so much more.

But for many refugees, the ID issued by UNHCR is their only identity card. It is the document that determines what we are able to do with our futures. The UNHCR ID is only valid for five years, and the process of renewing it can take two years, meaning that by the time you receive a new ID card, it is only valid for three years. When it expires, the cycle starts over again.

If I was designing UNHCR programmes, I would do everything I could to make sure people have both social security and the possibility to work to support themselves.

Even with a refugee ID, the process of obtaining a work permit or a licence to open a business in Kenya is a bureaucratic nightmare. Not having an ID card means not being able to do either of these things and also being left vulnerable to police harassment. We are made to believe that these people protect us, but, to many refugees, men in uniform are people we should stay clear of and avoid at all costs. This is both humiliating and strips us of the little dignity we have left.

So, we come back to where we started: People should have control over their own lives and futures; refugees are people.

If I was designing UNHCR programmes, I would do everything I could to make sure people have both social security and the possibility to work to support themselves. I would also try to maximise their ability to make their own choices about what they want to do and where they want to live.

If I learned anything from my mother, it is to loathe the thought of helplessness. That is what living in Kakuma camp meant to her. I watched her after we moved to Nairobi as she worked throughout the day and late into the night knitting and embroidering bed sheets with South Sudanese designs that she sold to provide for our needs.

My mother’s decision to try to find our way in Nairobi is one that single refugee mothers are faced with everyday. I don’t think choosing between a life of encampment – receiving bare minimum assistance from UNHCR – and choosing to be free to make your own life choices and pursue opportunities should be so difficult.

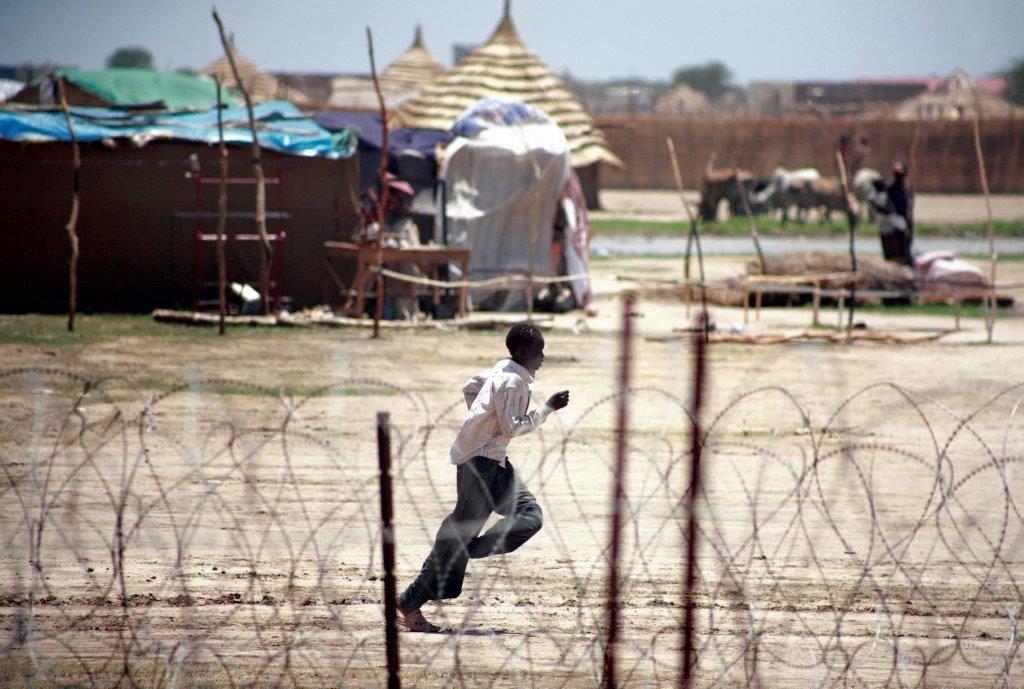

Edited by Eric Reidy. Picture by Petterik Wiggers