Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Tens of thousands of European tourists come to Gambia annually, while thousands of Gambians leave for Europe illegally. The number of Dutch tourists in particular is large. “Would the Dutch and British holidaymakers stay away, then the economy goes kaput,” says Marc van Maldegem, manager of the Kombo beach hotel near the capital Banjul. Welcome to “the smiling coast of Africa”, as Gambia advertises itself to tourists.

Welcome to the most unreal country in Africa, a monster of colonial history. The smallest country in mainland Africa is also one of the poorest. Therefore Gambians look elsewhere. “I will marry only with a Gambian in Europe, only then will I be assured of a good future,” says a girl in Bintang, a village located a hundred kilometers inland.

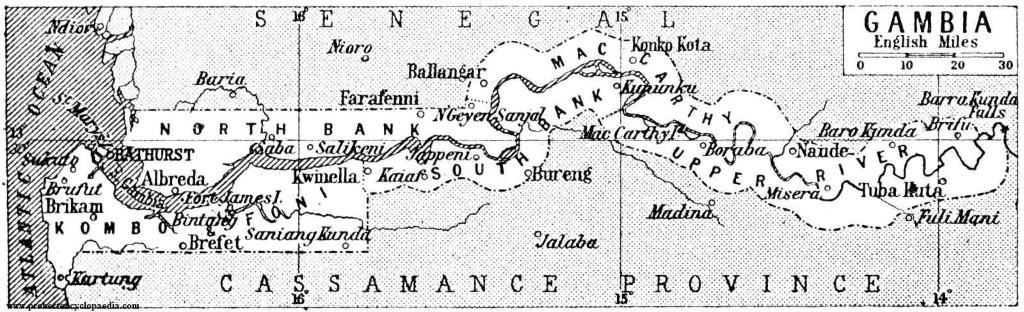

Gambia with barely two million inhabitants was born through competition between the French and British colonial powers. The French wanted the land, the British the river. In 1795 the Scottish explorer Mungo Park wrote: “The reader must bear in mind that my observations apply chiefly to persons of free condition, who constitute, I suppose, not more than one-fourth of the inhabitants at large; the other three-fourth are in a state of hopeless and hereditary slavery”. Gambia gained a place in the spotlight again because of slaves in 1977, with the book and TV series Roots by the American writer Alex Haley about the slave Kunta Kinte.

After the colony was founded in 1816 the English used Bathurst (now Banjul) as a supply post and base for suppressing slavery, which had been abolished in 1807. Long-term plans of Paris and London to exchange territory in Africa failed. Thus the independent country Gambia was born in 1965, a river state 24 kilometers at its narrowest, 50 km at its widest point and 470 km long. An experiment with the formation of the confederation Senegambia in the eighties did not end the historical accident called Gambia.

The local economy revolves around sex, alcohol and peanuts. During the European winter mainly older Dutch and British tourists enjoy Gambia for just a few hundred euro, laying on the beach in the hot sun and watching birds in the mangrove swamps. “How was the sun today?”, the staff of Kombo Beach Hotel ask the sunbathers every day. Marc van Maldegem agrees that a large proportion of tourists come for sex and alcohol. “We shouldn’t be so spastic about it,” he says. “It happens in many southern European holiday destinations, but there it concerns sex between white and white, here it raises eyebrows because it’s between white and black. These sex tourists are often lonely Europeans who come here and get love and affection from Gambians”.

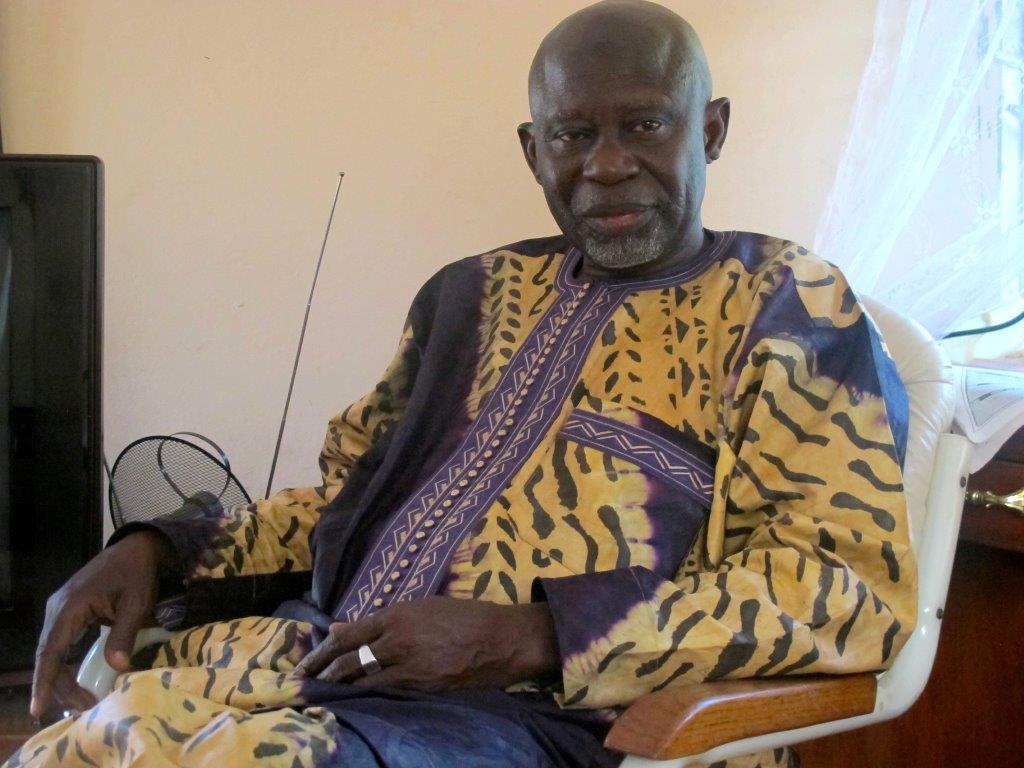

The politician Ousaini Darboe was a veteran opponent of Yayha Jammeh, the dictator with a superego who put Gambia on the map again by his erratic behavior in recent weeks. Adama Barrow appointed him as his foreign minister. Darboe mentions as one of the priorities more development of the tourism sector. A quarter of the economy revolves around tourism, the same proportion comes from remittances from migrants and the rest of the economy concerns companies owned by Jammeh. Gambia exports almost nothing, not even peanuts anymore. Darboe blames the poor economy for the high the migration. “Gambian migrants without work should return home. But not all at once, that would create problems for us.”

The population stays alive by farming and fishing. As before, everything evolves around the river. In the village of Bintang chief Bakari Sisse puts his wooden folding chair under a mango tree to seek protection from the sun. “Before, we used to live off fishing and agriculture,” he says. “But most young people have left for Europe. No-one is building boats anymore and the women who sold fish are unemployed. Each family has someone who departed for Europe.”

Gambia has percentagewise the highest number of migrants in the whole West African region. According to figures from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) 4.3 percent of Gambians are living abroad. In Italy last year nearly 12,000 Gambian migrants arrived, which is 0.63 of the population.

Has Jasju is a teacher at the elementary school in Bintang. He teaches his pupils about the dangers of “the back door”, a route through the Sahara and then illegally through Libya to Italy. “Migration has become an infectious disease, peer group pressure among young people. I cannot swim, so I’m not going.” One morning a colleague of his had left. “It is not openly talked about, but secretly families raise money for the trip of their children. In some villages almost the entire age group between 19 and 35 years is absent.”

The farmer Musa Badjie lives in the village Block along the Zeinab Jammeh highway, named after the wife of the departed dictator. His yard is full of mango trees. “When the mangoes are ripe, I let them rot. Because there is no fruit processing industry in Gambia”, he says. He fills the stomachs of his extended family with what he harvests from his two hectares’ field. “In the night secretly we go to the forests of Senegal and cut wood for charcoal there. In this way Allah keeps us alive. Every elderly person prays to Him to let our sons go to Europe.”

With an average income of two dollars a day Gambians have been looking for opportunities elsewhere for quite some time. “In the past villagers sought work in Libya but the chaos there after the fall of Gaddafi makes that impossible now,” says farmer Badjie. The 27-year-old Lamin left his job in the capital temporarily because of the political unrest and moved to his native village. He has a job in the tourism sector, but still wants to migrate. “You Europeans do not understand us,” he says interrupting the conversation. “We young people must take care of our parents and we want to build our own family as well. We feel that pressure every day.”

The best friend of Lamin was called Moloudi, a tourist guide. Moloudi was stranded in Libya three years ago at his first attempt. A year later he tried again and drowned in the Mediterranean. “I would rather have gone with him,” laments Lamin, “because now everyone sees me as a failure in my village. Tourism is good but a job in Europe is better”.

This article was first published in NRC Handelsblad on 10-2-2017

This article was first published in NRC Handelsblad on 10-2-2017

Pictures by Johannes Dieterich

Pictures: Ousaini Darboe, chief Bakari Sisse and last Lamin.