“Residents are now living in constant fear of death.”

By Ahmed Gouja

Local volunteers from the Shaqra Emergency Response Room prepare food for displaced people camped outside of El Fasher. Half a million people have been displaced from the North Darfur state capital in recent months.

Ethnic labels are slippery in Darfur. The term non-Arab refers to diverse groups including the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa who are usually described as “African”. Yet both “Africans” and Arabs are Black and Muslim, have been present in Darfur for centuries, and have intermarried. Some non-Arabs claim to have Arab ancestry and there are Arabised non-Arab groups.

While most Arab groups are nomadic herders of cattle and camels, non-Arab groups tend to be sedentary farmers. Conflicts between them have historically been rooted in the politics and institutions governing access to land and natural resources, drought events that have forced herders to encroach on farming areas, and the destructive interventions of Khartoum and other foreign powers.

Identities have been hardened and militarised during periods of war, but conflict has never been totalising. Though some Arab groups joined the Janjaweed in the early 2000s Darfur conflict, others stayed neutral. Likewise, in the current conflict some Arab communities have tried to stand against the war and oppose RSF mobilisation.

All communities in Darfur have historically been marginalised by Khartoum elites. Emergency response rooms are neighbourhood-based mutual aid groups that were set up across Sudan to respond to the conflict and the lack of international humanitarian support.

The groups draw on a rich heritage of social solidarity in Sudan, and now number several hundred across the country.

They are operated by thousands of volunteers, who make daily meals and keep services like power and water running. Still, despite increased recognition for the groups in recent months – topped off by a Nobel Peace Prize nomination – volunteers say they are underfunded and face repeated attacks by the warring factions.

In the besieged Sudanese city of El Fasher, residents say they are digging foxholes to survive indiscriminate missile strikes and eating noxious animal feed to stave off their hunger as food stocks fall and prices soar following months of bruising conflict.

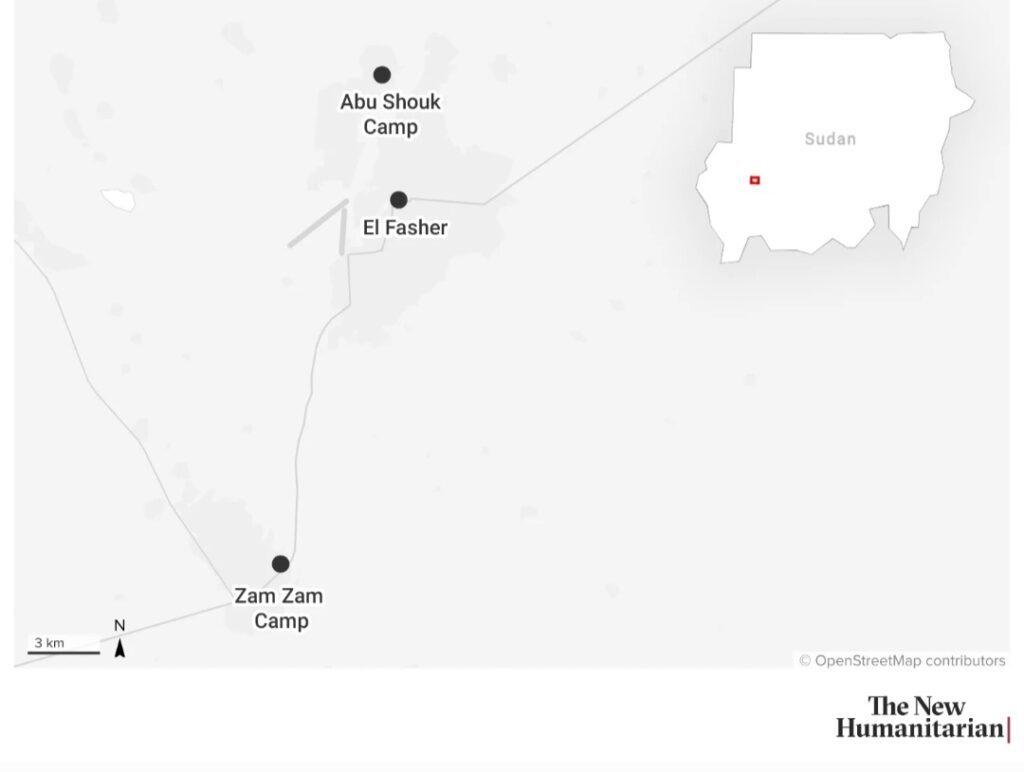

Close to half a million people have been displaced in the Darfuri city and famine has gripped a nearby camp since the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces began fighting the army there seven months ago, part of a nationwide war between the two forces that began last year.

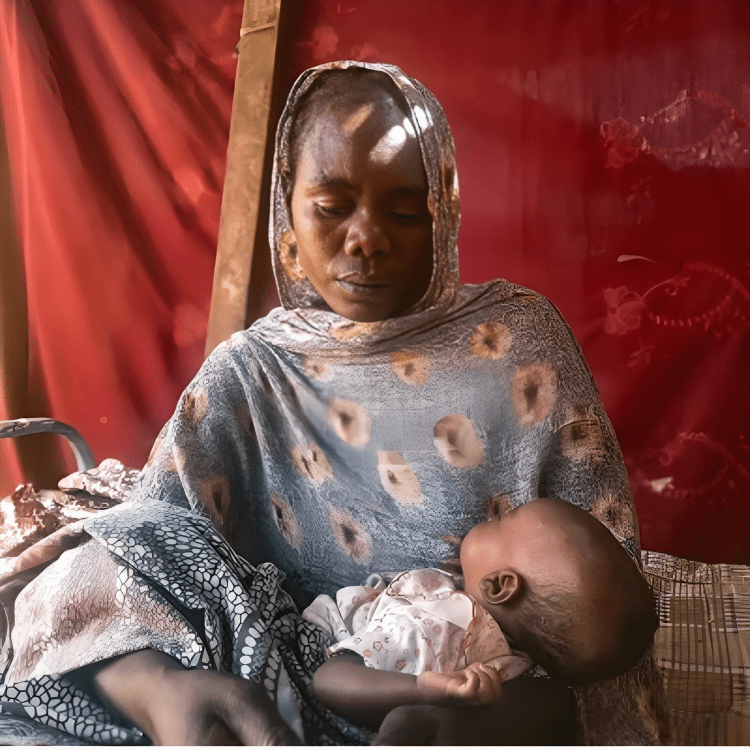

“I cannot bear to lose another child,” said Taiba Babiker, who lives in Naivasha displacement camp in the north of El Fasher. She said she lost a child several months ago due to malnutrition, and that her newborn is now suffering from extreme hunger too.

“She is showing the same signs of severe malnutrition that claimed her sister’s life,” Babiker said. “I try to find food and goat’s milk in the neighborhood, but I am unable to find anything. I am desperate, helpless, and afraid that history will repeat itself.”

El Fasher is the last major urban centre in the western Darfur region where the RSF hasn’t managed to fully oust the army, though its fighters are edging closer. The group also controls most of the capital city, Khartoum, and various other parts of the country.

The still-expanding war in Sudan has produced the world’s largest hunger and displacement crises, uprooting over 11 million people. It has also led to devastating urban warfare in places like El Fasher, which was, until recently, home to as many as two million people.

The RSF has imposed a siege on the city and controls most of its neighbourhoods. Some reports suggest it will soon seize full control, though sources in the army and aligned local armed groups said they will continue fighting no matter the cost.

El Fasher residents described a humanitarian emergency that is among the worst in Sudan, with hospitals being repeatedly targeted even as hundreds (or thousands) of people are being killed by artillery shelling and airstrikes, and many more are dying from starvation and disease.

Famine was announced in the Zam Zam displacement camp, just south of El Fasher, in August by technical experts – the first such declaration in the war. The situation has only worsened since, and similar conditions are thought to be prevailing in other camps in the city.

International aid groups have frequently been blocked from delivering assistance – because of either army and RSF obstruction or bad weather – leaving civilians dependent on local mutual aid efforts run by charity groups and youth-driven emergency response rooms.

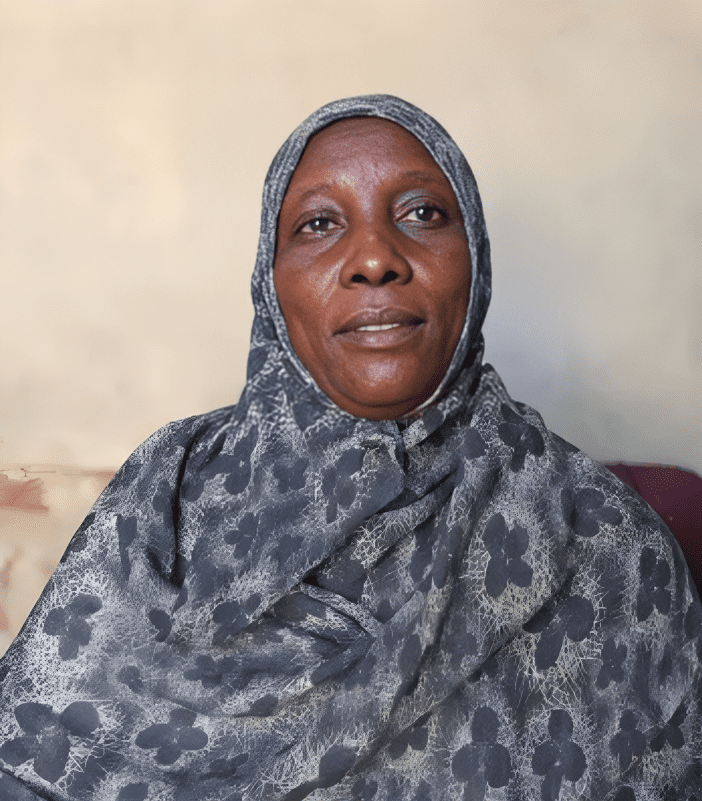

“In these dire conditions, the emergency kitchens and shelters in El Fasher have become the only source of food for many families,” said Hindiya Saleh Mahdi, an El Fasher resident, social worker, and community leader focused on supporting women in the city.

“We are facing the beginning of winter and, if we don’t act quickly, many more lives will be lost to the cold, as well as to the ongoing violence and hunger,” Mahdi told The New Humanitarian.

Taiba Babiker lives in a camp in the north of El Fasher. She lost a child several months ago due to malnutrition and her newborn is now suffering from extreme hunger too. (Journalist in El Fasher/TNH)

Hindiya Saleh Mahdi, an El Fasher resident and social worker, said emergency response rooms and local charities are the main groups helping people survive the conflict. (Journalist in El Fasher/TNH)

“Catastrophic” shelling

Sudan’s conflict was triggered by a disagreement over plans to merge the RSF into the army. However, the war echoes a longer struggle between military and political elites drawn from groups based in the centre, and challengers from marginalised peripheries like Darfur, which is the RSF’s home region.

The paramilitary group has fought a vicious campaign to kick out the army from Darfur’s five states, and its mostly Arab Rizeigat fighters have been accused of ethnic cleansing and genocide crimes, especially against the non-Arab Masalit group.

El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur state, had initially been a safe haven, welcoming vast numbers displaced by RSF offensives in other Darfur states. Yet a localised ceasefire in the city – brokered by community leaders – collapsed earlier this year.

Residents said fighting has been especially intense in recent weeks following the end of seasonal rain. The army has been steadily retreating from its positions, while the RSF has deployed drones and new forces, according to military sources on the ground.

Both groups have repeatedly struck civilian-populated areas with artillery fire or airstrikes, though the RSF accounts for the majority of attacks on infrastructure, including public hospitals – only one is still open that is capable of performing surgery.

Civilians trapped in El Fasher have been protecting themselves by digging foxholes and covering them with sacks of soil and old doors, said Hamdoon, a volunteer for a local emergency response room who asked for his last name not to be used.

Despite these efforts, Hamdoon said many residents have lost their homes due to attacks on residential areas, and a “significant” number have also lost their lives or sustained life-changing injuries.

“Innocent lives are lost every day,” Hamdoon said. “These are people with no connection to the conflict who are simply trying to survive. Residents are now living in constant fear of death.”

Mahdi, the social worker and community leader, said the economic situation inside El Fasher has become “catastrophic”, with shelling devastating the main markets, and the RSF closing off key roads as part of a siege strategy.

Some food is still getting in, but the price of the goods is extremely high, and even venturing out to purchase supplies is dangerous, multiple residents said.

”People are caught between two grim choices: Either stay and face death from shelling, hunger, or disease, or attempt to escape, which means risking your life along dangerous routes where there is no guarantee of survival,” said Mahdi.

Residents who have stayed behind said they are surviving by selling off personal items, including furniture and electronics – often to RSF-affiliated traders – and then buying food with the cash.

Many said they are also reliant on the communal kitchens, which are run by charity initiatives and the emergency response rooms. They fundraise from local philanthropists, diaspora benefactors, and international aid groups.

However, emergency response room members said their resources are far too limited, and that they are having to classify people by vulnerability levels even though everybody is sorely in need.

Most international aid groups have struggled to establish an operational presence in Darfur during the conflict. UN agencies, in particular, have complied with army restrictions on aid shipments into RSF-held areas, while the RSF has blocked access too when it suits its interest.

Famine-stricken camps

The situation is also critical in displacement camps inside and around El Fasher. They house victims of the 2000s Darfur conflict, which saw the state arm Arab ‘Janjaweed’ militias (they later morphed into the RSF) to crush mostly non-Arab armed groups.

Abu Shouk camp, which normally hosts some 100,000 people, has been especially impacted because army-aligned armed groups are using it to stage attacks on the RSF. The RSF fighters have responded by shelling the camp, razing thousands of homes.

On some days, several dozen mortar shells are fired into the camp, said Suleiman Abdul Rahman Yahya, a community leader representing a block on the eastern side of the camp, which is close to RSF positions.

“Displaced people are living in constant fear,” Yahya said. “They are unable to leave their homes to seek work because of the risk of mortar shells falling and killing or injuring their families.”

Emergency response room volunteers in Abu Shouk have been raising funds to evacuate people who lack the means to leave of their own accord, yet camp residents said the number staying still outweighs the number who have been able to escape.

Ahmed Mohamed Ahmed said the clinic where he works as a doctor in Abu Shouk has received over 500 bodies and more than 800 wounded people from within the camp in recent months.

Ahmed said many fatalities occur because it’s so difficult to evacuate people quickly to the one remaining hospital in El Fasher where many operations can be performed, and because even that hospital is lacking the ability to treat patients with certain life-threatening injuries.

Women and children wait outside a health centre in Abu Shouk camp. Health workers at the camp said malnutrition has become widespread across all age groups.

“In the entire city of El Fasher, there are fewer than a handful of specialists [still] working,” Ahmed said. “This severe shortage of medical expertise has led to the collapse of the local health system, and the situation is especially tragic inside the camp.”

Another camp badly affected by the conflict is Zam Zam, which is located 15 kilometres south of El Fasher and currently hosts half a million people. Many of them are newcomers who escaped besieged parts of El Fasher and other areas of Darfur.

The RSF has not yet targeted the camp, but since the August famine declaration – the first in over seven years in any country – only one World Food Programme (WFP) convoy has been able to reach the area, arriving last week after a two-week journey from Chad.

International medical groups, including Médecins Sans Frontières, are present in the camp, but they have struggled to bring in therapeutic food, medicines, and essential supplies due to obstruction by the RSF, which controls most supply roads in the area.

Local charity organisations and community kitchens have again been the main source of support for residents, said Qissma Adam Mohamed, an emergency response room volunteer based in Zam Zam.

Mohamed said many families are only able to eat a single meal each day and have been unable to harvest their crops due to RSF and aligned forces controlling surrounding agricultural land.

During the rainy season, Mohamed said many Zam Zam residents relied on vegetables that grow around homes without human input. Now, however, she said they are surviving on an animal feed called Ambaz, which is formed from the residue of peanut oil processing.

“Relying on the Ambaz meal for three consecutive days leads to severe diarrhoea and further complications in children,” Mohamed said. “As a result, cases of severe malnutrition have become widespread and critical in the camp.”

Mohamed described Zam Zam as a camp within a camp – with the main settlement for the long-term displaced people, and then dozens more settlements set up in schools, camp squares, and around the main market for the new arrivals.

On top of hunger and inadequate water infrastructure, Mohamed said Zam Zam is also currently experiencing a malaria outbreak and a livestock disease that has killed off people’s donkeys, which are crucial for transportation.

A long battle?

It is unclear how long the battle for El Fasher will go on for. No side currently appears willing to give in despite the massive and growing level of humanitarian suffering.

Though the RSF controls the majority of El Fasher, one senior RSF commander told The New Humanitarian that the group wants full control over the city and the camps, and to take revenge for the personnel it has lost during the battle – something it has done elsewhere on several previous occasions.

Other RSF leaders said its fighters feel that capturing El Fasher is necessary for the legitimacy of the group given that Darfur is their home region, and given their control over all other major urban centres in Darfur.

Still, the RSF needs to defeat not just the army but also previously neutral ex-rebel movements that are local to the area, and it needs to prevail over civilians who have been displaced in El Fasher and have joined self-defence groups.

Though there are reports that individuals from some army-aligned ex-rebel groups have retreated from the front lines and moved to Zam Zam camp, fighters told The New Humanitarian they will not fully fold and withdraw from the area given their local ties.

If the ex-rebel groups do collapse along with the army, the RSF is likely to punish civilians it considers close to them. The Zaghawa community – one of the main population groups in El Fasher – is especially at risk, given its representation among anti-RSF forces.

Ahmed, the doctor working in Abu Shouk, called for the international community and humanitarian organisations to “raise their voices” and demand an end to the RSF siege.

Hamdoon, the emergency response room volunteer, said the city cannot wait any longer for help: “If the international community does not act quickly, we risk losing what remains of our community.”

This article was first published by the New Humanitarian: