By Ilona Eveleens

A wide, dusty road ends in a gaping hole in the mangrove forest through which the water of the Indian Ocean is visible. A man appears from the remaining forest of trees that grow in the shallow, salty water along the coast. He carries a bag with two live crabs. “There are abundant crustaceans between the mangroves. But they will soon disappear when the new port of Lamu will be constructed”, he says.

In March of this year the Kenyan president Mwai Kibaki gave together with his South Sudanese colleague Salva Kiir and the now deceased Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi the go-ahead for a second port in Kenya. The other one in Mombasa is the supply route for also Uganda, Rwanda, East Congo, Burundi, Ethiopia and South Sudan. The new harbour will be constructed in Magogoni on the mainland, just opposite of the archipelago Lamu and some hundred kilometres south of Somalia.

Earlier this year the plans were dusted off when Sudan and South Sudan quarreled about the transport of oil through a pipeline from South Sudan to Port Sudan, a port in Sudan. South Sudan is a landlocked country and sought diligently an alternative for the oil export that provides the vast majority of government revenue. Kenya agreed to build an oil pipeline of 1700 kilometer from the South Sudanese oilfields to Lamu. Neighboring Ethiopia showed also great interest. The country is landlocked as well and a conflict with Eritrea deprives it from a nearby port. Ethiopia also wants to build a railway to Lamu.

The mega project, called Lamu-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET), is calculated to cost over twenty billion Euros. The three countries are not capable to finance such a huge project. The World Bank showed interest but only after an environmental impact report is done. The government in Nairobi seems not to be willing to go that way. President Kibaki reminded that the Chinese often finance without pre-conditions. He made the remark a day after the announcement that oil was found in Kenya, a product where the big energy consumer China always is thirsty for.

Lamu views the arrival of the harbor with trepidation. “We fear for the existence of the Swahili people. The port will crush us socially and politically and ruin our environment”, grumbles former teacher Mohamed Ali Badi, in the ancient Fort of Lamu. He is a member of Save Lamu, a group of activists. The group believes that the constitutional rights of islanders are violated with the port plans because they were not informed and consulted. The group also insists on a study on the impact of the port on the environment.

Lamu is one of the most idyllic resorts in Kenya. The islands host the oldest Swahili settlement in East Africa. In the seventh and eighth centuries arrived Arab and Persian traders along the East African coast, and mingled with the local population from which the Swahili people arose. UNESCO, the UN cultural organization, has declared Lamu a World Heritage site.

The clear water is a paradise for snorkelers and divers. The only motorized vehicles on the islands are the ambulance, the police car and a tractor. Transport is done by some 6000 donkeys. Lamu with a predominantly Muslim population has 22 mosques including some of the oldest in the world.

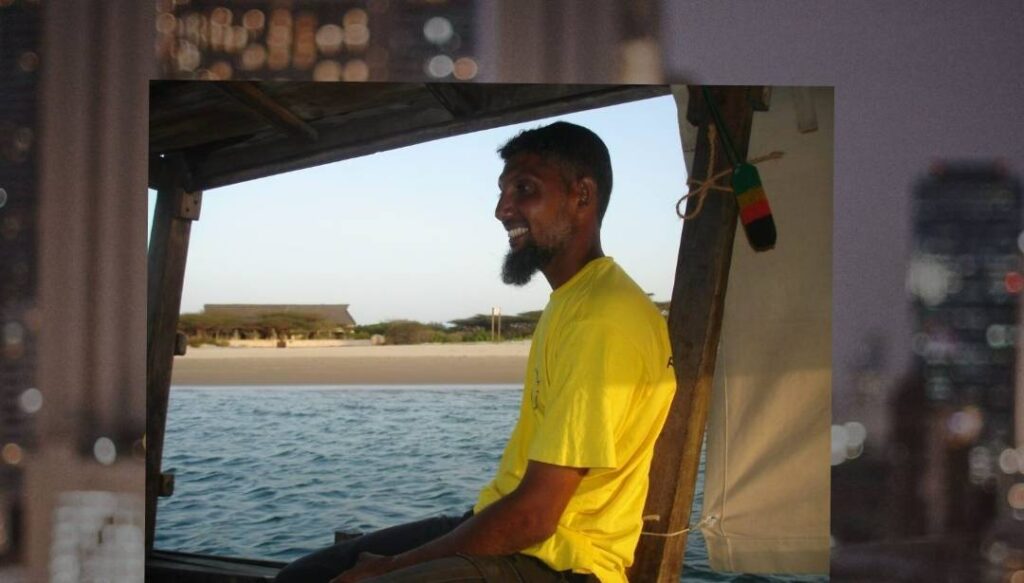

“Where the berths of the port must come, is now a breeding ground for fish. We fish in the traditional way in the lagoons where large school of fish can be found. If the port is coming, we will lose our income. Our boats are not big enough to go fishing in the open sea where floating fish processing factories are operating from China, South Korea and Spain”, says Somo Muhammad Somo. He leans against a wall on the largest jetty of Lamu where there is a hive of activity. Dhows, traditional wooden sailing ships, transport all kinds of goods such as crates of soda, cement, bales of second hand clothing and baby powder.

Abdulrahman Aboud looks at the activity. He trades in the wood of mangrove trees which is being used mainly in construction in Kenya. After massive cutting of mangrove wood for export, it is now only allowed to trade it within Kenya. “We, traders, adhere to environmental regulations and ensure that the mangrove forests are renewed. Now the government will go on an unlimited cutting exercise.”

Muhsin Kassim moors his dhow on the quay. He provides tourist trips on his boat. Also he is averse to the port plans. “The coral reef will be partially destroyed because a canal has to be dredged that is deep enough for the big ships. Not only is coral protected but it also keeps the sharks offshore. If the reef disappears and harks come within the lagoons, tourists can no longer safely swim and dive. ”

All three men belong to ‘Save Lamu’, which is supported by among others the Dutch foundation ETC. “We help to strengthen he bargaining power of the local community”, explains Wim Hiemstra of the Foundation.”Save Lamu is not against modernization but wants cautious handling of the environment.”

It is difficult to find proponents of the harbor. Abdalla Fadhil, former mayor of Lamu and property developer cannot wait for 2015 when the first part of the port should be ready. He holds office at a table in a restaurant in the old town of Lamu. He is the appointed chairman of a government committee which should inform the population about the port. “The port means development. This is an underdeveloped area of Kenya and it is high time we catch up with the rest”.

He insists that the port will bring employment. Especially young men are jobless and are hanging around the jetty and in the small alleys on the archipelago. More than half of the island’s population lives below the poverty line of one dollar a day. Abdullah Fadhil believes that a port will offer more stable employment than tourism.

He is not worried about the felling of mangrove forests and the disappearance of the fishery. “The disappearance of the forests is unfortunate but will be replaced by a whole new city for half a million people. City and port will offer great employment opportunities.”

The transport corridor to the northern neighboring states will run partially through marginalized areas in northern Kenya. Land speculators are already active in the corridor while others are involved in raunchy land grabbing. This causes great concern to Ali Obo. The Swahili man earned his money in tourism in Lamu and purchased farmland. His farm will soon be placed right next to the harbor. He has his title deed but is a minority within the 60,000 indigenous residents. “Most of them live on land and in homes, often for hundreds of years, long before the country Kenya became into existence. The majority though have not managed to get ownership papers.”

He notes that he is not talking about the Swahili who sold their their land and homes to foreigners or hotel chains. His concern is the islanders who live below the poverty line. Corrupt officials constitute for them an impregnable barrier. “These people are basically squatters, their land can be taken any time,” fears Ali Obo. “President Kibaki promised recently all islanders a title deed but people have little confidence in political promises that are not written on paper.”

The estimated 50,000 residents from other parts of Kenya, all possess a title deed for houses and land. They are predominantly members of the Kikuyu people who have their original habitat in central Kenya. They left Central Kenya because of lack of land and settled in neighboring Tanzania. When the policy of nationalization was introduced there it left those Kikuyu homeless. Former Kenyan president Jomo Kenyatta, a Kikuyu, offered the displaced in the seventies land including in Lamu. Sometimes even natives were dispelled to create vacant land. Since then there is little friendship between the two groups. “Swahili fear to be evicted of their land by a government that is very close to the Kikuyu people. The Swahili have no documents to claim their possessions”, notes Ali Obo.