The helicopter lands on a field that is littered with bullets. We have arrived in Gwoza, an area in northeastern Nigeria where only military vehicles can safely reach the cities. In the surrounding countryside, the militias of the Boko Haram terrorist group still prevail. Mostly women live in Gwoza. Their husbands were forced to remain in the countryside, captives of Boko Haram.

Today, the weekly military convoy has arrived with goods. The soldiers also brought new displaced people. “Stand in rows, we must do a body check on you”, a soldier commands the refugees. “Do they really think we may be planning suicides?,” protests Gaji Saida.

The church of Gwoza

In August 2014, Boko Haram hit the headlines when they captured Gwoza. Their leader Abubakar Shekau proclaimed the city the headquarters of his self-named caliphate and announced a covenant with the Islamic State. The male part of the population fled Gwoza into the Mandara Mountains. The warriors took along the remaining women, including Gaji Saida, to the neighboring Sambisa forest. The attacks are still similar to this: they try to kill or recruit men and make women into slaves.

The loss of Gwoza made the once mighty Nigerian army look like fools. It tasted defeat against the ragtag fighters of the terrorist group. But the tide has turned. In March 2015, the army recaptured Gwoza, and now the garrison town has become an important base in the ongoing struggle against Boko Haram in the countryside.

Ama, a government soldier, points to the Mandara Mountains nearby. “We’ve repeatedly attacked Boko Haram there, but they know how to hide well. We just need to apply guerrilla tactics as well,” he says.

Ama shows the regained self-confidence of the army. Between 2013 and 2015, Boko Haram could occupy an area as large as Belgium because of the army’s weakness. Nigerian soldiers ran away for Boko Haram, because their salaries were stolen by the higher ranks in the armed forces. Only when South African mercenaries and the armies of Cameroon, Chad and Niger appeared on the battle scene, and new army leaders were appointed, was there a reversal. “Now we go to the terrorists and when we find them and enter a firefight, we’ll beat them. Give us some time and the uprising is over,” says soldier Ama.

No end to suffering

Woman in displaced camp

But with military successes, there has been no end to the suffering of the population. In Northeast Nigeria alone, 2.3 million people have been driven from their homes. In the neighboring countries, another million are displaced. As more areas are conquered and opened up, more malnourished people arrive in camps in cities. Over the past two months, the population of Gwoza increased from 40 to 60 000. In camps live another 20 000 people, including many severely malnourished children.

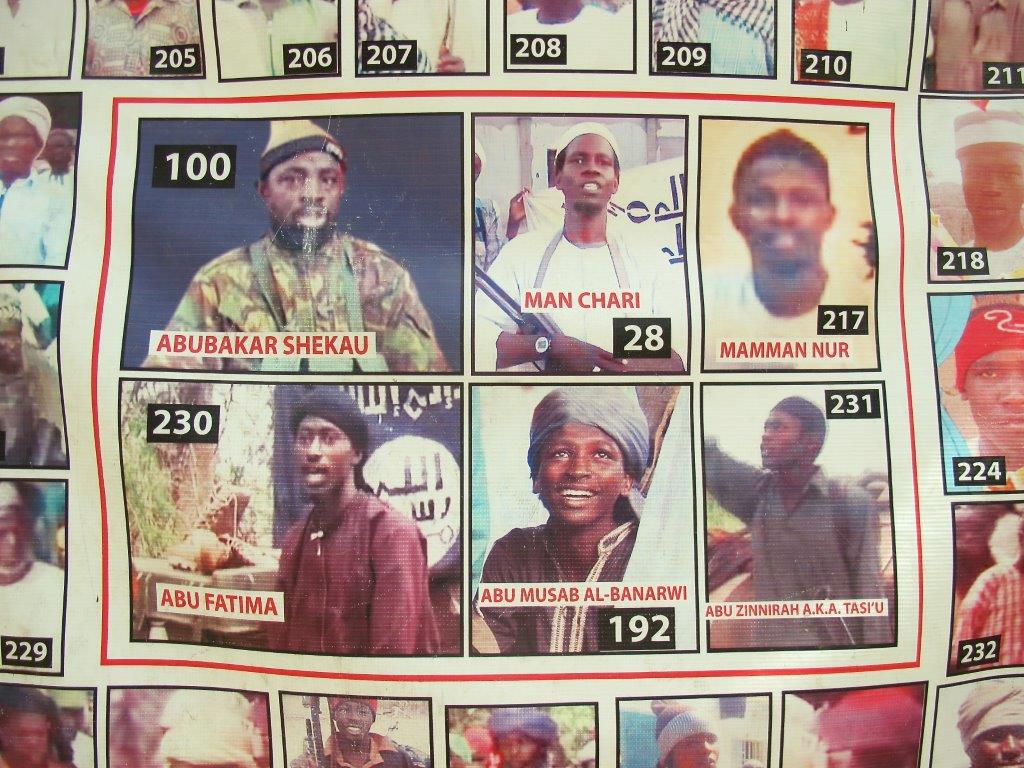

Pockmarked walls with drawings of weapons, a broken-down clinic, a detroyed church: the Shekau warriors beat everything into pieces. At the entrance of the barracks in Gwoza hangs a poster “Wanted” with the images of the leaders of Boko Haram. A nervous soldier with a monkey on a string keeps us from taking photographs. “This is a security zone, it’s dangerous here,” he says angrily.

After the recapture of Gwoza, no one can leave the town. Yesterday, a woman went to collect firewood outside the town and she never returned. The danger of Boko Haram is everywhere. They stay in the mountains and the forests and hide among displaced people.

Dilemma

“The men are not allowed to leave Boko Haram’s territory and in government they are suspected of being terrorists and are therefore questioned for weeks in barracks,” says an aid worker. “Groups of mere men roam around in the countryside, in flight for everyone”.

The women are barely doing better. The have escaped from rape and whipping by Boko Haram and can go to displaced camps in the cities, but the food is scarce there. Human Rights Watch calls these sites “similar to concentration camps”.

The aid worker sees the dilemma. “From a military perspective, the new policy has produced good results,” he says. “But the army must consider the consequences for the population. You can not keep residents in these camps, the situation is untenable and us as foreign aid workers are implicitly involved in maintaining this bad situation.”

In this way, the turnaround in the battle against Boko Haram offers little perspective for the population. Borno has always been among the poorest and most marginalized states of Nigeria. Before the war, only 17 percent of residents could read and write (in the southern city of Lagos it is 92 percent). Now the region has fallen back even further. Children have not gone to school for the last four years and farmers have not been able to plant new crops for years.

When Muhammad Yusuf, Boko Haram’s first leader, offered his followers Quran education and social projects, thousands of young people volunteered to join him. The police executed Yusuf in 2009, after which under his successor Abubakar Shekau a far more radical Boko Haram emerged, with more brutal violence and less social activity. From that time of Yusuf’s rule, the group has still well-educated members in its ranks, such as doctors and civil servants. Some commanders carry literature written by the revolutionary Mao Zedong. They strive for power, not for the propagated Islamic state of utopia.

“Boko Haram is one of the most mysterious terrorist movements,” says the head of a UN organization. “I worked in Syria and many other crisis areas in the world, and I always maintained contact with the opposition. But in Nigeria, we know almost nothing about the opponent.”

Much more than the Islamic fundamentalist uprisings in Mali or Somalia Boko Haram feeds for its rebellion on local grievances. The mysterious movement has splintered into four or five factions. Those under Shekau operate in and around Sambisa forest and are the most violent, destroying villages and setting children up for suicides. Most of his victims are muslims. Abu Al-Banarwi, son of founder Mohammed Yusuf, operates around Lake Chad and targets his attacks on christians and government infrastructure. Other factions concentrate on kidnapping for ransom, which the terrorists earned millions.

Harun Ahmed is an imam. Boko Haram killed his father and uncle, just like him muslim preachers, and set fire to their religious books. Harun sees an identity crisis among young people as the main cause. “My generation still refused to listen to quasi-religious propaganda like the one coming from Boko Haram. But young people are now easily intimidated. They feel ignored by the state and just hang around in the villages.”

Does he see an end to the crisis?

“In the current situation, it remains attractive to join Boko Haram, to be able to carry a gun and loot.”

This article first appeared in NRC Handelsblad on 10-5-2017