Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Agronomist Onesmus Mongare (30) digs his fingers into the rotting mass of maggots and waste. This is his gold: organic fertilizer made with the help of the black soldier fly, as an alternative to artificial fertilizers and pesticides. “Kenyans no longer know what they eat. Farmers spray as much poison as they want, as long as it brings in money,” he says between the green hills just outside the capital Nairobi. Agriculture has purely become a business in Kenya. “How can I bring love to my crops if I only farm for commercial reasons?”

Organic farming currently accounts for less than one percent of food production in Kenya, however the sector is growing. Because artificial fertilizer, although heavily subsidized, is becoming more expensive. And according to the Ministry of Agriculture, 63 percent of the arable land has become acidified due to excessive use of artificial fertilizers and pesticides. This has led to degradation of the land, fewer nutrients in the soil, and erosion. Kenyans have not been taking good care of their fields and the environment in recent years. They have cut down forests, polluted rivers and used excessive amounts of chemical fertilizers. Mongare: “Our ancestors were already organic farmers, but today’s farmers have been taught that only the use of chemicals guarantees good yields.”

Onesmus Mongare

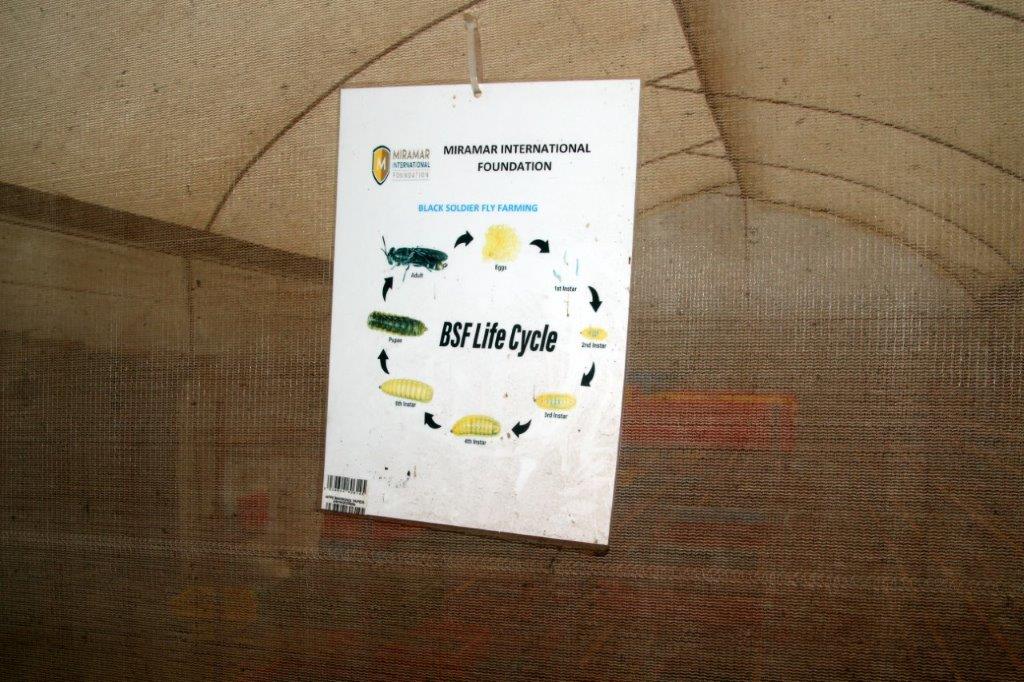

Organic farming employs compost and animal manure as fertilizers, as well as biological pesticides to safeguard crops against pests and diseases. Crops are cultivated and livestock are reared without the use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, genetically modified organisms, or antibiotics. This helps maintain the quality of soil, water, and air quality. Organic farming utilizes locally sourced materials, which keep the costs low for the farmer. “The fertilizer we make using the larvae of the black soldier fly is three times cheaper than the chemical fertilizers you get in the shops,” Onemus Mongare says proudly.

Eating habits

Farmers used to produce mainly for their own consumption, using plant waste as fertilizer. “The big change came in the early 2000s when the government made the import of fertilizers and pesticides cheaper. That was the beginning of a different type of agricultural sector,” Mongare explains. In 2008, the government started subsidizing fertilizers. “A middle class also emerged with different eating habits. We used to eat bread only on special occasions, now we start every day with it. We want milk from cartons and chicken from KFC, Kentucky Fried Chicken. Back then, when we ate cassava and other root vegetables, we were stronger and more resilient.”

Africa faces significant challenges in achieving food self-sufficiency. Despite possessing two-thirds of the world’s uncultivated agricultural land, the continent allocates approximately $60 billion annually for food imports, as reported by the African Development Bank. This expenditure is projected to escalate to $110 billion by 2025, driven by rising demand and evolving consumption patterns. For the numerous small-scale and often impoverished farmers, who are responsible for the majority of food production, the adoption of cleaner and more cost-effective agricultural methods is crucial. In Kenya, agriculture accounts for over a quarter of the nation’s gross domestic product, with the economy valued at more than $300 billion last year.

Rotting waste

The Kenyan Ministry of Agriculture has recorded a decline in maize production and in key exports of horticultural produce and tea. Most of Africa’s food comes from smallholder farmers, not from large-scale plantations. According to James Kagwe, an organic farmer, these small producers are being pressured to use artificial fertilizers. “In the eyes of many, a field has become a food production company. As a result, we have lost our spiritual connection to the land.”

The sweet smell of rotting waste welcomes visitors to Kagwe’s plot of land in Naivasha, a town ninety kilometers from Nairobi. Reusing green waste is an important eco-friendly aspect of organic farming. Kagwe makes fertilizer for sale and for use on his own field. His son drives a tuk-tuk through the city streets to collect the waste, while a hunched woman removes plastic and metals from the household waste. According to James Kagwe, most of the household waste is organic. “We can reuse that,” he says.

James Kagwe in Naivasha

On his field outside the city, he builds a house from shoes, fake hair, bottles and other waste products. In addition, he cultivates sixty different crops that mutually support one another and enhance the soil, including indigenous varieties such as fruits, pumpkins, cassava, sweet potatoes and all indigenous. “That’s how my ancestors did it too.” He strokes the moist earth. “You can feel that it is healthy, it is alive and smells good,” he says with satisfaction. His land, cultivated with organic waste, looks jungle green, while his neighbour’s field, cultivated with artificial fertilizer, only has withered maize plants. Kagwe, scornfully: “His land became exhausted, by constantly growing maize and using excessive amounts of artificial fertilizer.”

James Kagwe has a message and when expressing his ideals he sounds like a priest; organic farmers like him are often full of idealism. After the colonials introduced commercial, large-scale agriculture in Kenya, the bond with the ancestral land was diluted. Indigenous crops such as yam and cassava made way for maize and wheat. James Kagwe longs for that past: “We have to go back to nature. That is wisdom. And that is more than the knowledge with which big food companies try to talk us into artificial fertilizers and pesticides.”

Monsanto

A hundred kilometres to the north, in the Nyandarua district, publicist and environmental activist Betty Guchu has a shop for organic pesticides. “What a farmer can earn with his land is now a priority for him,” she complains. In her area she encounters more representatives of Sygenta, a producer of pesticides, than of the Ministry of Agriculture, which has clean farming in its banner. “Representatives of companies such as Sygenta and Monsanto, the world’s largest producer of seeds, trap farmers. They give these farmers credit, sell them seeds and fertilisers and then they are stuck with these suppliers. But who tells the farmers about the dangers of pesticides for their own health and that of the earth? Only after a while do they see that their fields are dead because of the use of chemicals, some of which come from Europe where their use is banned.”

The doubling of the price of a 50-kilo bag of fertilizer – from the equivalent of 35 to 70 euros as a result of blockades caused by the war in Ukraine – was partly offset by the government through higher subsidies. But earlier this year, a scandal came to light in which the ministry had supplied fake fertilizer consisting mainly of lime and sand. At least two of the companies contracted by the government to supply the fertilizer had cheated. “That got farmers thinking. Since then, I have seen more and more customers coming to my store to buy organic products,” says Betty Guchu.

Els Breet on her farm

Dutch entrepreneurs

The rising demand for organic products within the European Union has resulted in a significant increase in the number of Dutch entrepreneurs engaging in organic farming in Kenya. A notable instance is the Kenyan company Yielder, founded by Alexander Valeton, which has provided training in organic farming to thousands of farmers.

Els Breet (50) farms near the village of Ngecha. Ten years ago, she had three customers, now 110, who receive a basket of vegetables delivered to their homes every week for 10 euros. She now cultivates more than eight hectares with eighty employees, most of them women. And schoolchildren go on trips there to get to know the farming profession again.

With her boots in the mud, she looks out over her little green paradise. A truck full of goat manure arrives. “What do you earn with organic farming, people sometimes ask me. But you shouldn’t think like that,” she says, “I don’t know how many kilos I’m going to harvest and sell, that kind of thinking doesn’t belong in organic farming. Non-organic farming, on the other hand, works with forecasts, there’s money to be made quickly. I let nature do its work. Organic farming is a passion.”

A worker on Els Breet’s farm

This article was first published in the NRC on 17-09-2024