Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

The white hospital tents are surrounded by a puree of mud, shit and waste. Latrines nearby spill over and children splash in a lake with waste water of foreign aid workers. Inside the tents children scream and mothers wail. Nora Echaibi, dressed in wellington boots, gives a tour of what they here call a hospital, a facility run by Medecins sans Frontieres Holland.

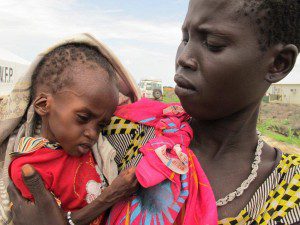

In the reception tent an emaciated child is weighed in a laundry tub: eight months old with a weight of four kilo’s.

In the next tent are young men with amputated limbs, victims of the bitter power struggle which broke out in December between President Salva Kirr and his former Vice President and now rebel leader Riëk Machar. Nora Echaibi wades through the mud and says: “And now we go to the worst tent”.

“That little child will not reach the end of the day,” she points to one of the dozens of mothers clamping their babies to their bodies. A silent cry jolts against the ribs of his small chest. Pneumonia. Besides diarrhoea, malnutrition and malaria, this is the leading cause of death in the camp of 45,000 displaced persons near Bentiu in South Sudan. “Fifteen percent of the children in the camp is severely malnourished, a percentage that indicates an emergency “.

A mother begins to weep loudly. Her child has just died and Nora Echaibi tries to comfort the woman. This is the fourth death in “the worst tent”, and it’s only two o’clock in the afternoon. “It will get worse today,” she predicts.

Toby Lanzer, UN humanitarian coordinator of the United Nations, calls the situation in South Sudan an “almost catastrophe”. “I do not see any light at the end of the tunnel. The rainy season has started. Almost all roads are unpaved, and it is increasingly difficult to get through the mud to reach victims. Cities and markets were destroyed by the fighting and traders have fled. In large parts of the country people could not plant because of the violence. The damage has already been done, even if fighting would stop straight away”.

He uses superlatives to combat a lukewarm response from donor countries. “By the end of the year the situation will be just as bad as during the great famine in Ethiopia in the eighties. There exists in the world a huge disappointment about what is happening in the youngest nation and that frustrates me a lot. ”

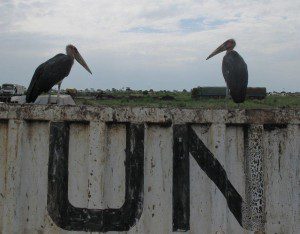

Of the eleven million South Sudanese inhabitants four million need help, more than one million are displaced in the country itself and 400 000 walked to neighbouring states. Tens of thousands of civilians sought protection in camps of the United Nations, which were intended for the accommodation of peacekeepers and are not equipped to lodge masses of hungry and sick people.

In the four sections of the camp near Bentiu, the Dinka and the Nuer have been separated. What began as a power struggle within the ruling party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), degenerated partly in brutal tribal killing. President Kiir is a Dinka, Riëk Machar, a Nuer. Bentiu, which was occupied twice by rebels since December and is now again in government hands, is in Nuer territory.

Nyakuoth, mother of six children, scoops the mud out of her shelter and starts cooking porridge of millet on a fire of reeds. “The Dinka’s destroyed my house in Bentiu. The Dinka’s murder us”. She means government soldiers. She does not dare to go outside the camp to gather firewood. “We are afraid to be killed. Or they do the terrible thing to us”. She means rape, a taboo which is not discussed openly.

A young man called James Michael shits in the open, this part of the camp lacks toilets. “Always rain, always floods. I wish I had a piece of plastic sheeting at night to protect me”.

Throughout the day he does nothing and is terribly bored.”I wish I could go to school again”. His father got stranded in a UN camp in another part of the country; he lost his mother during the fighting. He sends his youngest sister to fetch firewood. “She runs less risk that the terrible thing happens to her. You must be very brave to go outside the camp”.

The morgue in the hospital is next to a shed where the first suspected cholera patient has been separated. Nora Echaibi washes the children’s bodies; she removes the needle of the infusion from their arms, wraps the bodies in blankets, puts them in white plastic bags and hands the packets over to the mothers.

Another child died in the last hour, the fifth kid today. It’s three o’clock in the afternoon when the four wheel drive car filled with the mothers and their white packets works itself through the mud a way out of the camp for the funeral.

The women walk through the tall rustling vegetation to the already dug holes. They seek a pit not filled with rainwater, they lay the corpses on the wet ground and make a cross of reeds.

A sob, a prayer and men splatter the wet soil on the plastic bags. A little further four UN soldiers stand guard, because even for a funeral it is not safe outside the camp.

This article was first published in NRC Handelsblad on 1-7-2014