Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

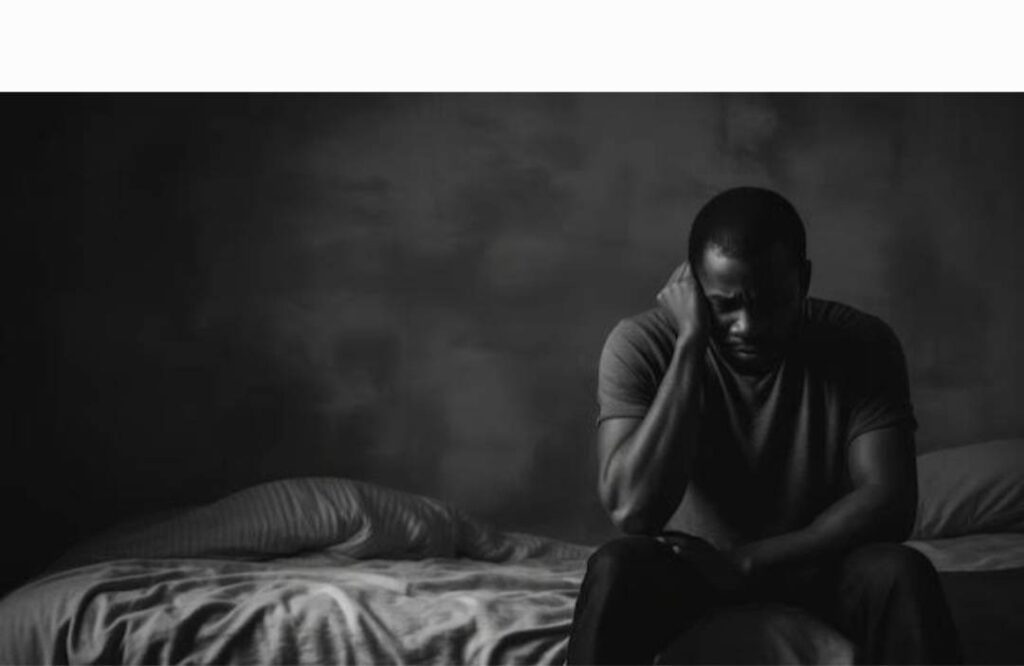

Following the genocide, the struggle with trauma and loss manifests as an an invisible war.

Similar to the situation in Rwanda, the ethnic violence between Hutus and Tutsis continues to linger in the memories of survivors in Burundi. It is hardly talked about, and people are looking for ways to heal the scars of trauma and loss.

Dieudonné (42) often wishes he had died as well. His parents, older brother, and friends were all killed, targeted for being Hutu. In the world that was left behind, the dead seem blessed. “It’s not easy for me to tell this,” he says, making a cutting gesture with his hand along the side of his stomach. “They cut my mother open with a machete. The soldiers said: ‘You must suffer first before we shoot you dead.’” Helene, his seven-year-old sister, had watched and later told Dieudonné about the murder. Dieudonné himself was not present because his parents had thrown him out of the family a few months earlier to live off the streets. Dieudonné’s voice falters, his eyes become wet. “This happened a long time ago, it was 1993, but the images kept haunting me and my sister. We had no life.”

African wars are marked by a staggering number of victims, with hundreds of thousands losing their lives. However, the true horror extends to the millions who survive, including both victims and perpetrators. The brutal conflict between Hutus and Tutsis known from the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Burundi, which has a population of 85 percent Hutu and 14 percent Tutsi, shares a similar past. Although the fighting is over, the suffering is not over yet.

The violence was intimate. Tens of thousands of murderers killed not from a distance with bullets and bombs, but up close in personal confrontations with machetes and clubs with spiked knobs. Neighbor against neighbor, mothers against each other’s children, husbands against their wives. Half a million people were killed in the various rounds of ethnic violence in Burundi’s long trail of blood since independence in 1962. The biggest massacre came in 1972, started when Hutus rebelled against the Tutsi regime, which did lead to eliminating almost all well-educated Hutus. After Tutsi soldiers shot dead the Hutu president Melchior Ndadaye in 1993, a civil war broke out between Hutus and Tutsis, with hundreds of thousands of victims. Can you continue peacefully as a nation then?

Unhealed dividing lines

After the death of his parents, Dieudonné worked his way up from street boy to student. Now he teaches at the reception centre Oeuvre Humanitaire pour la Protection et le Developpement de l’enfant en Difficulté (OPDE). It is located at the foot of the hills of Bujumbura and provides vocational training for the thousands of street and former rebel children. The government forbids the centre to offer overnight sleeping places for the homeless. “Then you would be taking in too many of them,” sneers director T.

Poverty and war, the social fabric has been destroyed by it. “Humanity has diminished, in their anger men immediately reach for a machete. Once you have killed, it remains easy to kill,” he says. “People can no longer rely on each other, especially if you belong to the other group.”

What lies ahead after a genocide, when the physical suffering has ended and the survivors try to pick up their lives? In muddy camps with blue United Nations tents, international aid organizations kept hundreds of thousands of Burundian displaced people alive for years. That’s where the assistance stopped. Upon their return, the government organized no trials or reconciliation attempts, there are no regular commemoration events. The country prefers to play hide-and-seek with its past, for fear that unhealed dividing lines would become visible again.

Reconciliation is about dealing with trauma, there is a common problem that requires individual solutions. In Western psychology, healing is often seen as revisiting painful memories. However, in Burundi, many people endure their pain quietly. The country has just four psychiatrists. In 2007, there was only one, and currently, 48 are in training.

On the hills of Bujumbura lies the Centre Neuro Psychiatrique, in the residential area of Kamenge where Dieudonné’s parents lived. In this Catholic center made out of red bricks, patients wait with tense muscles on wooden benches for their daily therapy. Therapist V. (48) gives them pencil and paper to draw their parents. “After the war ended, a cold war began in people’s minds,” he says. “Victims still encounter perpetrators, murderers avoid relatives, returning displaced persons encounter those who attacked their families with machetes in their fields. That creates new psychoses. The patients in our clinic often come from the areas where the violence was most intense. Many residents there commit suicide, sometimes dozens in a few weeks. We are a sick society.” His patients share their drawings. The one of a boy shows his deceased family members in bizarre shapes.

Psychologist P. (41) looks at the lethargic patients slowly making their way to their dormitories past her office. She was born during the civil war. “With the pungent smell of corpses in the depths of your lungs, with images on your retina of people blown to pieces by grenades, with the memory of roadblocks where victims wait, frozen, for their slaughter, these horrors brand the brain of every child,” she says. Distance yourself, rationalize, is her advice, try to replace the bad images with good ones, a murder with a wedding, an explosion with a graduation party. “If that is too much effort for you, if you are unable to look at your father’s murderer, perhaps you should go and live separately on another hill, as some Hutus and Tutsis do now.”

Tears flow inwards

Everywhere along the side of the road from Bujumbura northwards to the city of Cibitoke, young people, mostly returned refugees, hang around aimlessly. In the distance on the mountain tops, farmers are overexploiting the last bits of vacant land with their spades, sometimes with a climbing rope tied around their waists.

N., who is employed at a psychiatric clinic in Cibitoke, tells about four women have come forward in recent days due to experiencing sexual violence within their families. “Excessive alcohol and drug abuse, family quarrels, prostitution, robberies on food kiosks, all this antisocial behaviour is caused by poverty,” he states.

War, corruption and the flight of the middle class have led to extreme poverty in Burundi, the poorest country in Africa. This unites, but perhaps it also hides the trauma of the war. The title of a book by Pacifique Irankunda, a Burundian who grew up during the war, is: A man’s tears flow inwards. “Here it is accepted that you do not talk about traumas,” N. explains. “It is dangerous, you have to admit what you have done. So you talk along with your ethnic group, whether you are a victim or a perpetrator. Life today is already traumatic enough due to poverty.”

Burundi and Rwanda, following their troubled past, became heavily militarized in both society and politics. In 2015, people in Bujumbura witnessed hundreds of bodies lying in the streets once more. President Evariste Ndayishimiye’s ruling party supports a violent youth militia that, after a failed coup by Tutsi officers, took to the streets with hatchets, sparking a new wave of ethnic violence.

In a better neighborhood of Bujumbura, in a villa on a cobblestone street, musicians, writers and filmmakers gather in a studio on a Sunday afternoon. For the Hutus and Tutsis among these artists, ethnic differences do not seem to create barriers.

We Burundians never tell the truth, they start the conversation. “That is why our language has so many metaphors,” explains doctor and cartoonist Arnaud Badogomba, euphemisms for non-offensive language. “When a mother hits her child, she cries out: ‘don’t cry’. You never show your feelings.” His friend Alain Ingabire strums a guitar and sneers: “Burundians either seek revenge or become schizophrenic. But in our studio, we give people the chance to open their minds.”

Arnaud Badogomba

New world

Badogomba creates images of reconciliation in his cartoons. Like when, long ago, people mixed a few drops of their blood, put them in beer and drank it to settle their differences. On the wall they painted Le Petit Prince. “He flew to another planet to find the best flower and when he didn’t find it, he returned to cherish his own flower,” Badogomba explains Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s book. “Try to improve your situation, as we do here, don’t flee to another planet. We artists create a new world.”

It was only two years ago that Dieudonné dared to organize a commemoration ceremony for the murder of his family. His sister Helene couldn’t muster the courage and stayed away. Everyone cried, for hours. “Everyone needs someone,” he says. “I’m trying to develop humane thoughts again.”

In his attempts to rationalize his fantasies, he began to realize that he wasn’t the only victim. “Both Hutus and Tutsis were killed, that realization gives me the strength to carry on. Shortly after my parents died, I did not yet understand how we were all wounded inside, how difficult it is to find peace. But now a generation must rise up that frees itself from that past.”

One day he got in the car and took his children to Independence Square. “I had slept on the street there. My son saw a street boy and said: ‘Dad, watch out, he’s a thief.’ I said: my child, maybe his parents were murdered too.”

Due to the sensitivity of the subject, the full names of the interviewees have not been used at the request of the editors.

Thanks to Lidewyde Berckmoes, of the African Studies Centre Leiden who has been studying the intergenerational consequences of war in Burundi.

This article first published by NRC on 20-12-2024