We agreed to meet at the zoo in Maiduguri. There, the two girls aged nine and seventeen and the thirteen-year-old boy feel comfortable talking about their captivity under Boko Haram, the Nigerian terrorist group which in eight years killed an estimated 20,000 civilians and drove millions more from their homes. The face of the nine-year-old girl gets tense and she moves evasively as she remembers the strokes of the whip. The boy holds his hand on his throat during his story about an execution. The seventeen-year-old avoids eye contact when she talks about her rape. They are the victims, but could they also be the perpetrators?

Every loud noise seems to cut into their soul. Like the helicopters of the Nigerian government army which take off from Maiduguri, the capital of the northeastern state of Borno. The population has doubled to two million because of people fleeing for Boko Haram. Nobody travels outside the city without military escort.

The three children narrate their story of the past two years. It began when just before dawn Boko Haram’s warriors attacked their village of Kukawe near the border with Chad. Everyone ran out in all directions and in the panic they lost their parents. “Suddenly we were all alone,” says the boy. They reached Lake Chad and just when a fisherman wanted to take them across, Boko Haram fighters arrived. They shot the fisherman dead and took the children to their camp.

The boy got military training and every day he had to climb onto the top of a tree, to be on the lookout for the Nigerian army. The task of the youngest girl was to get water and collect firewood. After three days the oldest was assigned to a warrior as a wife. “He hit me every time he raped me,” she says with a squeaky voice. The thirteen-year-old boy lived with the men. “One day they called all boys together. They had captured a government soldier. Slowly they cut his throats open. ‘That happens when you try to escape’, they warned us.”

A friend told him that they would stay in the camp all their lives if they did not try to escape. After the daily Koran lessons, when all the warriors left, they fled. The oldest girl took the lead and they wandered through the bush for two weeks, until they met some nomads. They pointed them the way to a United Nations camp in Chad. “Aid workers returned us to Nigeria last month, where we live in a camp again. Someone told me that our parents are dead. We do not want to believe it, because thinking of them allowed us to survive for two years under Boko Haram.”

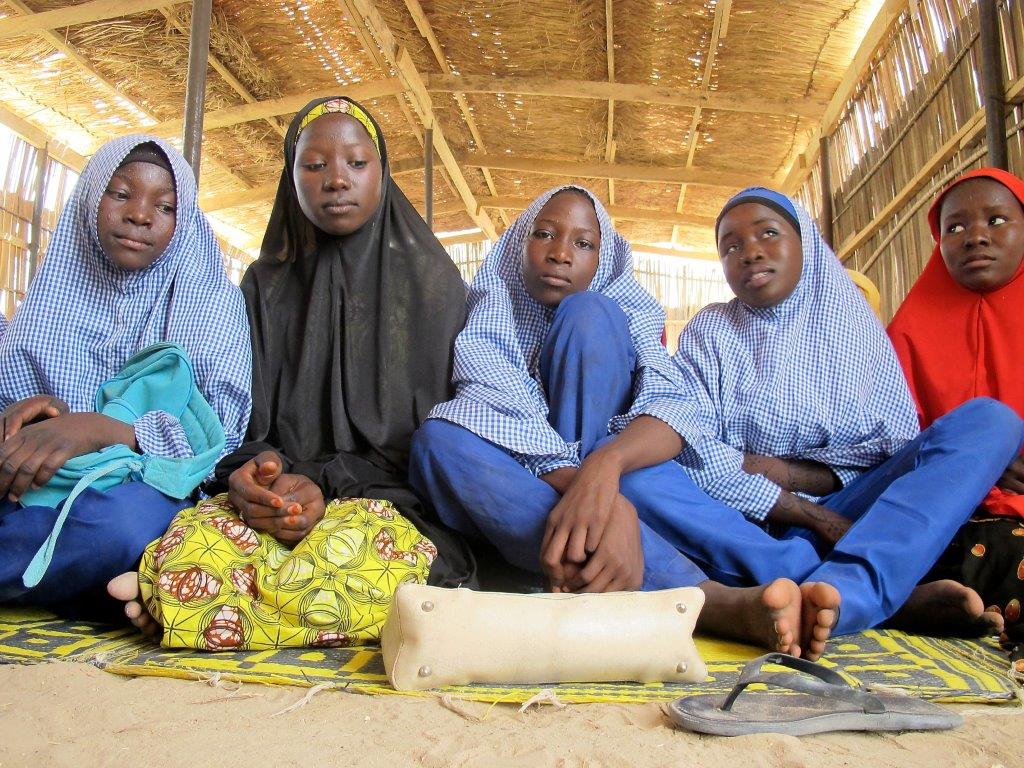

A few hours before our meeting in the zoo there were two bomb attacks in Maiduguri. Suicide bombers again. This time only the perpetrators, two girls, died. In April three years ago, Boko Haram abducted more than 220 children in the town of Chibok, most of whom are still in their hands. Unicef, the UN Children’s Organization, published a report to mark this day. Boko Haram is increasingly adopting children as a weapon. “Since 2014, 117 children have been used to carry out bombings, of which 80 percent are girls,” writes Unicef. Since early this year, more than 30 children blew themselves up, at mosques, schools, in camps for displaced persons and on markets. The government captured 1,499 children from Boko Haram last year. “The soldiers don’t differentiate between victims and perpetrators,” says Mausi Segun of Human Rights Watch. The more than twenty girls from Chibok who were released last year after negotiations with Boko Haram, could return to their parents for Christmas but stay in “preventive detention”.

The Chibok girls got international fame thanks to social media. But Boko Haram also abducted thousands of children from other villages and towns. Like in November 2015, 500 students in Damasak. “After the kidnapping in Chibok without any opposition from the government army, Boko Haram saw the value of children,” says Mausi Segun. “They had conquered large pieces of land for which warriors were needed. Some of them are brainwashed to perform suicide attacks. ”

Aid workers talk about “so-called suicide bombers” because a ten-year-old does not know what it’s doing. “We recognize them because they walk unstable”, a soldier says at a roadblock. Only one girl at the very last moment decided to drop her suicide belt. Just when she wanted to detonate her bomb, she saw a relative and that woke her up out of a coma. She told the police that her father, a Boko Haram warrior, did send her to blow herself up. “The suicide bombers are exhausted by hunger and Boko Haram promises them food after the explosion. Or they are drugged”, explains the soldier.

Violence upon violence

The conflict in Northeast Nigeria is one of the most horrific in the world; it is characterized by its extreme violence almost unprecedented in Africa at its scale. It consists of many layers: social marginalization of Borno, marginalized young people seeking salvation in religion, a misbehaving government army and civilians and victims of Boko Haram who unite in revengeful militias. Violence was put upon violence, resulting in a fragmented society without grounds for human values. An implosion of a desolate underclass, the horror spectre for Africa when a government fails to take care of its people.

Who can imagine how people change over months of imprisonment, how their minds adjusts to survive? Some children try to kill their parents because the warriors claim that Boko Haram is now their family. Some girls who escaped got pregnant in captivity and await a freezing welcome at home, so they voluntarily return to Boko Haram. Therefore, no victims mentioned in this article want their photo’s to be taken or their name mentioned for fear of his or her community. Boko Haram has caused distrust and stigmas, trauma that an army of psychiatrists cannot face.

An old man sits apathetic in a displaced camp in Maiduguri. Heartbroken. Sixteen of his children and grandchildren were kidnapped by Boko Haram. “I cannot even die in peace,” he says, “not before I know their fate.”

This article first appeared in NRC Handelsblad on 15-4-2017