Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

This story was written in 1989. 35 years later I went back to the same place to see whether there has grown a real village. That story will be published soon.

There is no road to the boma, there is no electricity and the residents have to dig deep for water. There is no store. The nearest school is a four-hour walk across the plains. One hundred and fifty people live in thirty shelters in the boma. The boma, inhabited by the formerly nomadic Samburus in Northern Kenya, has yet to develop into a fully established village.

The moon has risen to its highest point as the sun begins to rise on the horizon. The donkeys emit their first plaintive cries, a camel stretches its legs and an impatient calf presses its nose against the abdomen of its still resting mother. Flames light up on the fire in the houses.

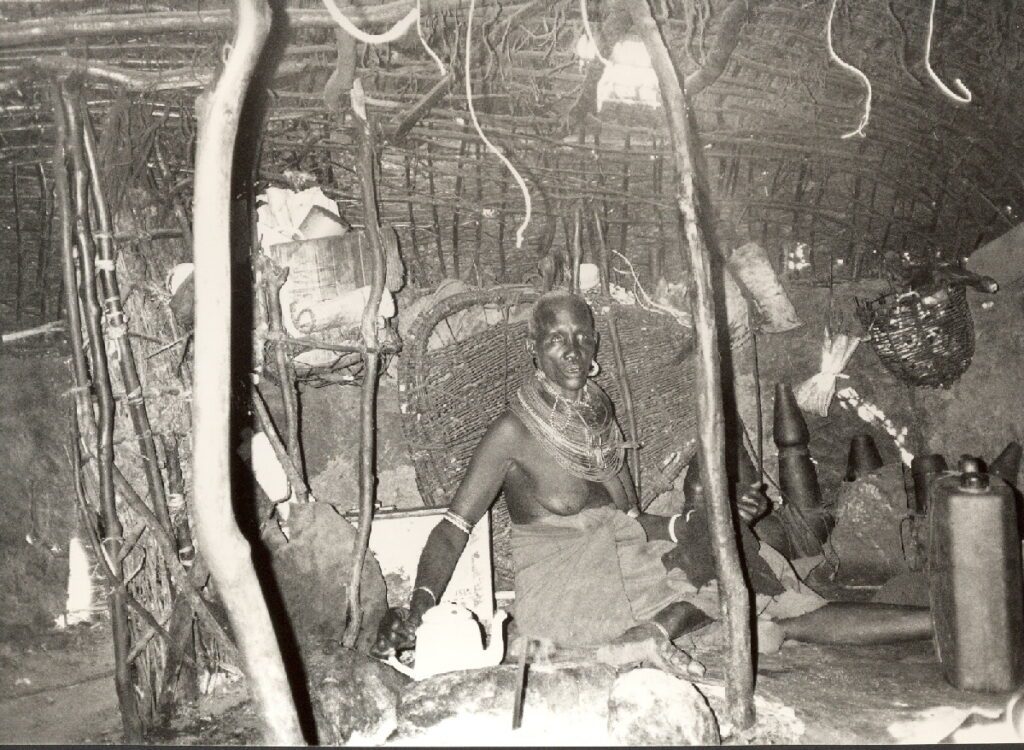

Old Busuké straightens up, rubs her gray hair and spits into the ashes of the fire. She throws in two twigs and the fire immediately starts smoking. The young warriors in the house respond to the acrid smoke with a rolling grunt, but continue to sleep.

Busuké glances at the warriors and realizes that she is late this morning, she hurriedly grabs the gourd and goes to milk her cow. When she returns after twenty minutes, the warriors are sitting up and waiting for their cup of tea. The first rays of sunlight penetrate the holes in the ceiling when Busuké serves her tea at a quarter past six. The day has started in the Samburu boma.

“Today, I’m going to look for my donkeys,” says Litikison, “they’ve been missing for four days.” “Okay, I’ll go with you,” a warrior promises. “Then let us go and give water to the cows,” Kurupa suggests to a fellow warrior, “that hasn’t been done for several days.” It has not rained for several months and the nearest water hole is a few hours walk from the village. The other seven warriors do not want to work today, they are going to eat meat.

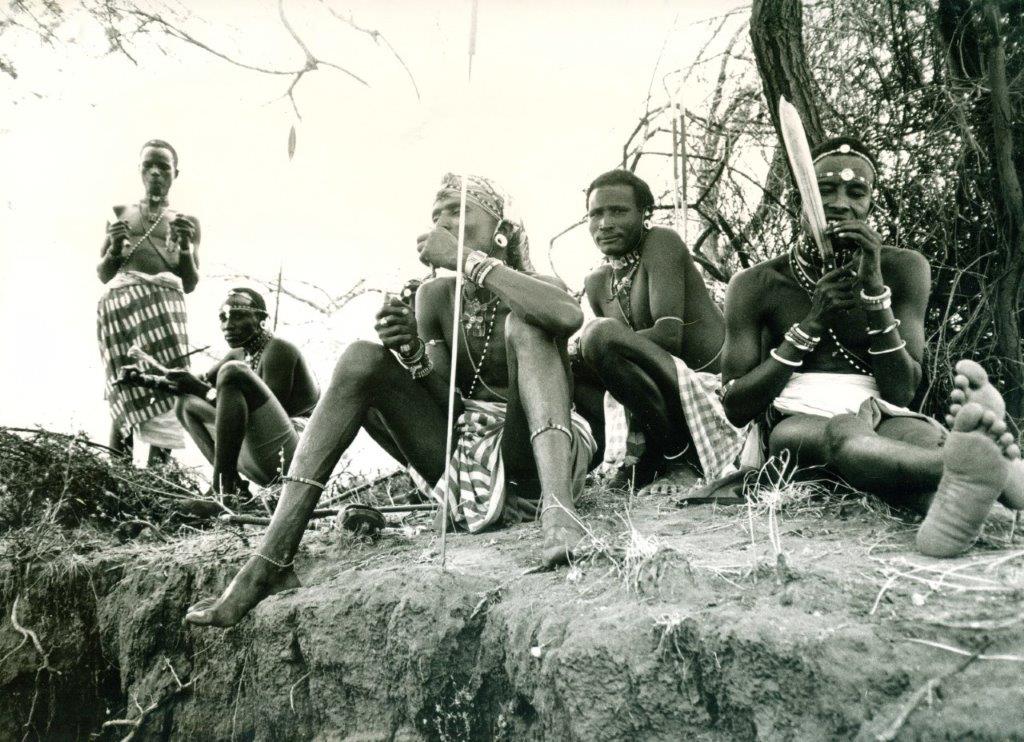

The Samburu boma appears abandoned as the seven morans (warriors) emerge from the thorny enclosure around eleven o’clock. The men have dispersed across the plains with their cattle, while the girls are out with the goats. Only a handful of children and elderly women remain in the boma. Busuké engages in household chores within her hut, sealing the roof’s gaps with a blend of cow dung and mud.

Equipped with a spear and a club, the seven morans diligently search for traces of their goats and sheep. At a dry riverbed they meet them, herded by a young woman of notable beauty. The morans exchange appreciative remarks among themselves. Upon approaching her, they maintain a formal demeanor, keeping a distance of two meters and refraining from shaking her hand. They inform her of their intention to slaughter a sheep. The girl nods in acknowledgment, retreats, and does not reappear. Ibeshon selects the plumpest sheep and hoists it onto his shoulders, transporting it to a sheltered area. He assumes the role of butcher for the day, while Oliam will handle the roasting.

Ibeshon squeezes his fist around the struggling beast’s snout. When the sheep has lost consciousness, he cuts the vein in the neck with his knife. The blood flows in a wave movement into the skin that has been cut open in a bowl shape. Every moran slurps his share of the warm sweet blood. An hour later, the seven are munching on large pieces of roasted meat. The blood, the flesh and especially the exclusive atmosphere of morans among themselves sets tongues wagging.

A formidable challenge, far exceeding the act of killing a lion with one’s bare hands, confronts the Samburu people. Kenya’s nomadic world has all but ceased to exist in recent years. Space was running out and the government wanted to be able to control its citizens. The Samburu had to settle. The boma’s that used to provide only temporary shelter will become permanent and grow into full-fledged villages. In the meantime, the former nomads must take their place in a new Kenya, where the agricultural peoples have claimed their share of power much earlier.

“The world is changing quickly,” says Lonis Lemelen as he takes a bite out of the sheep’s heart, “maybe the world will disappear. People kill wild animals, they cut down trees when new ones are not yet growing and they eat all the grass. We Samburu know this is wrong. People, wild animals, trees and grass belong together. We know when the grass has become too short and we have to move elsewhere. Humans have no right to murder other creatures.”

What is your first wish? “Water,” the seven shout in unison. In the dry months, the morans and their herds have to walk for several days in search of grass and water. It takes the women who remain in the boma hours to dig up drinking water.

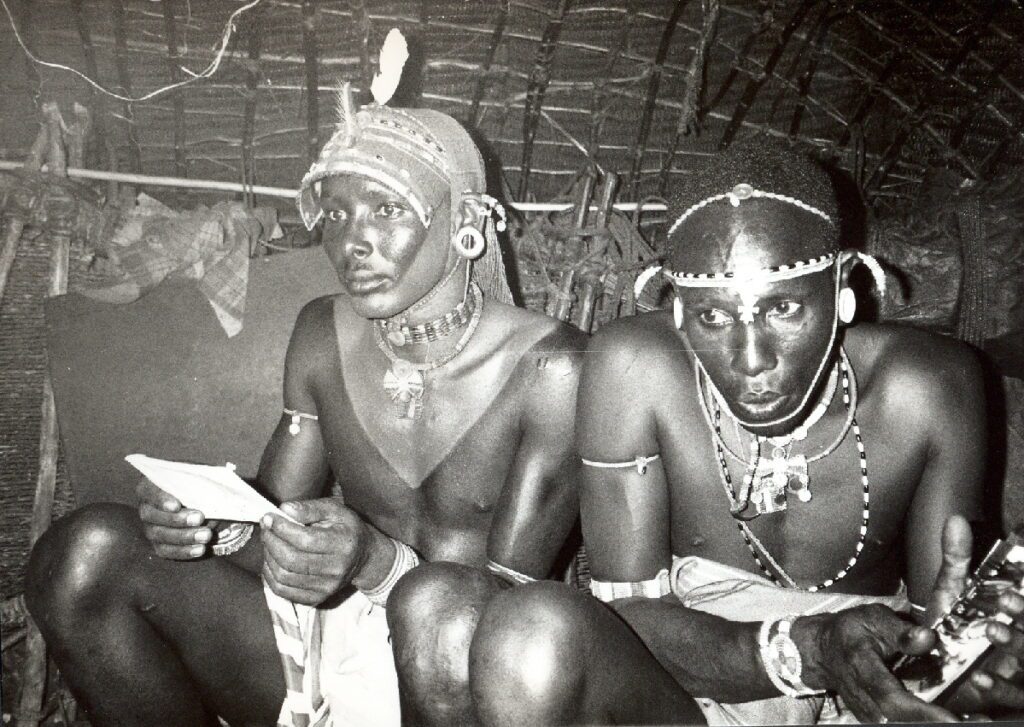

Lonis Lemelen (right)

Stone house

Ibeshon’s first wish is a house made out of stone in the boma. Everyone remains silent, no one supports this idea. Ibeshon is the only one of the fifty morans in the boma who goes to school and can read and write reasonably well. Of the one hundred and fifty inhabitants of the boma, only he speaks Swahili, Kenya’s national language, well. Yes, he even understands five words of English. In short, he participates in the new emerging world that brings new wishes.

“I want a wife first,” Lonis Lemelen breaks the silence. “What good is a stone house if there is no family living in it? And I would like to send my children to school.” A discussion arises about school. What are the benefits of letting your children enjoy education?

Ibeshon: “I have become happier since I have gone to school. I can write my name, read signs and know where Mombasa is.”

The other morans look at him questioningly for more arguments. “I can walk around confidently in Nairobi. And when people put a piece of paper under my nose to deceive me, I can contradict them,” Ibeshon continues. The others respond in agreement to this.

The sheep is almost eaten. The intestines, stomach and bones are wrapped in the skin and the morans return to the boma. The terrain is rough, the sun bright and the heat exhausting. But morans never complain, that’s what they are warriors for. Upon returning to the boma, Busuké’s tea awaits. She receives the remains of the sheep. Ten minutes later, children are everywhere in the boma chewing on intestines or chewing on sheep bones.

Opposite Busuké’s home is the hut of ol-payiam (old gentleman) Larata. He has three wives and countless children. The older the more authoritative, it is self-evident among the Samburu. The Samburu have no central authority, the elders make decisions collectively. They hold their discussions in a special enclosure in the heart of the boma, where they enter into contact with God.

“We older people must fully agree with each other before we make decisions,” says Larata, “if one is against it, we continue talking. We listen to his arguments and if they are good we may even implement his choice.” Doesn’t that take a lot of time? “I don’t understand what you mean,” Larata answers, “what matters is that we Samburu stay together. A few years ago we spent a week talking about a marital dispute. This we have been discussing for four days about a moran who slept in another boma with a girl who had already been claimed. By the way, there hasn’t been a single problem in our boma for two years.”

Busuké in her house

Banned

The elderly can impose severe punishments. “Above all, we demand that the guilty party apologize, he must surrender,” Larata explained. “In case of a murder, the guilty person is banished from the area. We used to go with our spears to the guilty party’s boma and take away his cows. These days we report a murder to the people of the government.”

Larata views the changes of the last ten years with mixed feelings. “It is good that our children go to school and learn to read. Because that’s just how the world goes. My daughters are also allowed to go to school,” he says generously. “And once they have gone to school they can still get married. But I would never marry someone who went to school. Because she can speak a language that I don’t understand. Then she is above me and that is unacceptable to the Samburu.” Larata cannot clearly grasp what drastic changes the introduction of education will bring about in the boma. “When my children are educated, they can teach me something. But I can tell them how it used to be. And that is much more important.”

He remains silent. He wants to say something else, but searches for his words. “Even though some of our children now go to school, we Samburu are still together,” he finally says belligerently. Larata is worried about the future, that’s clear. When women and children will be empowered through education, and perhaps know even more than the older men, what remains of the traditional relationships between young people and old people, between men and women? The authority of the wazee is in danger of being undermined.

The starry sky frames the existence of the Samburu, they know many celestial bodies by name. Larata wants to know something. “Nowadays I see new stars walking across the sky, at high speed. Can they explain at school what kind of stars these are?” No one in the boma has heard of satellites yet.

An old gentleman from another boma reports to Larata. One of his sons wants to marry one of Larata’s daughters. That poses a problem, because Larata has already promised this daughter to someone else. “Even if there turn out to be twenty men who want your daughter, I will ensure that she becomes part of my family,” the old man begins the negotiations with determination. At the end of the afternoon the two old gentlemen decide to postpone the discussions until tomorrow. Larata then calls Lemelen over. “Moran, when will you finally choose your wife? We older people have been talking about it and urge you to hurry. Almost all morans have already made their choice. They are now waiting for you before they can get married.”

Lemelen has been complaining for years that marriage is so terribly difficult among the Samburu. “You have to negotiate with the parents for weeks before they are willing to give up their daughter,” says Lemelen. He has enough girlfriends for the night, but getting a wife, that takes so much time. Many nights he lay awake wondering how he could find a wife. Larata offers help. He selected a candidate in another boma far away. Although Lemelen does not know her, he shows himself full of hope again. “Maybe now, with Larata’s help, I will be married within a few weeks.”

Spears

Around half past six, the boma glows in the setting sun. The cattle saunter into the enclosure. A precious young goat is selected to sleep in the house for the night. The older women each milk their cow, singing a special song. With crossed legs and leaning on their spears, the morans look attentively at their riches on four legs. A child lies on his back between the two humps of a resting cow. He curls up and playfully slides down the hump and along the nose of the animal. The cow calmly lets the boy go over him. There is perfect harmony between the Samburu and their cattle.

It is high time for another cup of tea with fat milk and many spoonful’s of sugar. A few morans stick their spears in the ground at the opening of Busuké’s house and crawl inside. The morans do not live in a specific hut, they eat and sleep where they feel most at home. The boma as a whole is their home. All the huts look identical. They are low and cozy, everyone huddles together. In one half there are hides to sleep on, in the other part the fire burns where the woman of the house stay with the favorite goat. There are no windows.

Along the walls hang gourds and a long red sock in which the sugar is stored. The building style of the boma and the houses virtually excludes private property. There are no house doors or cupboards. “The problem for us morans who work in Nairobi is that everything we leave behind disappears,” says Raale, laughing. “Washing powder, sugar, clothes, beads, you name it, everything of mine belongs to everyone when I’m not here.” All belongings “disappear” automatically into the collective. Only cattle are private property.

This collective attitude does not promote a favorable investment climate. In a neighboring boma, a moran recently opened for the first time a shop. He sells washing powder, tea and sugar. It turns out to be difficult to act businesslike when your customers are your comrades. Moreover, old Mr. Larata does not understand the necessity at all. “That’s our store,” he points to his goats. “I don’t worry about food, because there is always meat and milk. And if the rain fails to materialize, I turn to God.”

The evening is half full. The young people are taking over. Raale makes a growling sound that rolls from the depths of his body and culminates in a musical scream. Other morans follow him. Young girls with perky breasts are now trickling into the hut and singing with their high voices over the male basses. The voice as a musical instrument, the choir grows and grows in strength. The song tells about a lion. Around twelve o’clock the morans go outside, followed by the girls. In the middle of the boma, where the cow dung is the softest, eighty morans and girls are now dancing. In separate groups of course. The stimulating music of voices stirs up the spirits, everyone is carried away, it cannot be otherwise. The morans jump higher and higher. Litikison loses his senses, four morans have to hold his shaking body. Foam forms around his mouth. The moon begins its ascent from the crystal clear sky. It’s just another night in a Samburu boma.

Friendship

“I’m going to walk a bit,” Jos announces his intention to pick a girl for the night. Samburu have free sex. Sleeping with women is part of the daily rhythm. Their culture is ‘sex positive’, which means that sexual contact is encouraged as a virtue from an early age. Sex is probably the only thing the Samburu practice privately. Every moran goes to that house where he thinks he will find a good partner tonight.

More important than sex between a man and a woman is camaraderie between friends of the same sex. “There is nothing more important than friendship,” says Lonis Lemelen as he walks back to Busuké’s house with four morans. “Friendship means that you always carry someone in your heart and you want to see him regularly. Friends share everything. You as a friend can of course sleep with my wife.”

How do you achieve that unity? “We Samburus bond with each other, even if some of us have left for the distant city. The elders have taught us to form a unit. It has been like this ever since the Samburu came into the world. Maybe we are different from everyone in the world,” Lemelen explains. Busuké wakes up and wants to make tea again when the five morans enter. She looks a little disappointed that there are only five tonight. “I want, I have to take care of my children, it would be very bad if I were alone,” she says sleepily. The morans growl, stretch their legs, blow their noses, wipe the snot on the wall and spit one last sludge towards the fire. Then they lie down to rest in the narrow space, like five fingers on one hand.

All pictures by Mr Koert Lindijer

This story was first published in September 1989 in NRC Handelsblad