After Denise gave birth to a peacekeeper-fathered child in 2016, in the Beni region of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, she was hoping to get thorough support from the UN, the soldier, or from the country where the perpetrator was from.

Yet eight years on, as the UN peacekeeping mission (known as MONUSCO) draws down its troops from DRC, Denise said she is struggling to put her daughter through school and knows of many other women who are in the same position.

“We have always demanded two things: either substantial compensation that can help us guarantee good care for our children, or that MONUSCO gives the children to their fathers,” Denise told The New Humanitarian, asking for her real name not to be used.

On the ground for 25 years, MONUSCO and its predecessor mission have one of the worst records on sexual exploitation and abuse of any UN peacekeeping operation, with 272 allegations (some involving multiple perpetrators and survivors) against military personnel, according to a public database that tracks peacekeeper misconduct.

Almost 190 paternity claims have been raised against the peacekeepers, though there are likely hundreds more women and girls who have not come forward to MONUSCO because of fear of retribution or because they didn’t know the process.

The peacekeeper misconduct, combined with a perception that MONUSCO has failed to adequately protect civilians, has led to widespread public disaffection with the mission, which is one of the longest and costliest deployments in UN history.

To understand how women with peacekeeper-fathered children are feeling about MONUSCO’s departure – which is supposed to happen soon, though there is no clear date – The New Humanitarian spoke to mothers as well as local community leaders.

The interviewees – who are all from the restive Beni region – described rampant sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers, and said a lack of support for peacekeeper-fathered children has left them in desperate financial situations.

Similar problems have beset other UN peacekeeping missions, with troop-contributing countries often refusing to cooperate with DNA testing procedures and failing to enforce child maintenance payments.

MONUSCO spokesperson Ndèye Khady Lo said the mission strives to provide children fathered by peacekeepers with assistance tailored to individual needs, including medical, psychosocial, and legal support, as well as access to education.

However, Lo said paternity is the individual responsibility of the child’s father, and the payment of child support is subject to the laws of the member states that are contributing peacekeepers.

Lo said efforts to address sexual exploitation and abuse involving peacekeepers will be a priority for UN agencies that remain behind in DRC once MONUSCO finalises its withdrawal.

“While the disengagement of the peacekeeping mission is ongoing, the UN country team will remain and will receive and address any new reports of sexual exploitation and abuse, including paternity claims,” Lo said.

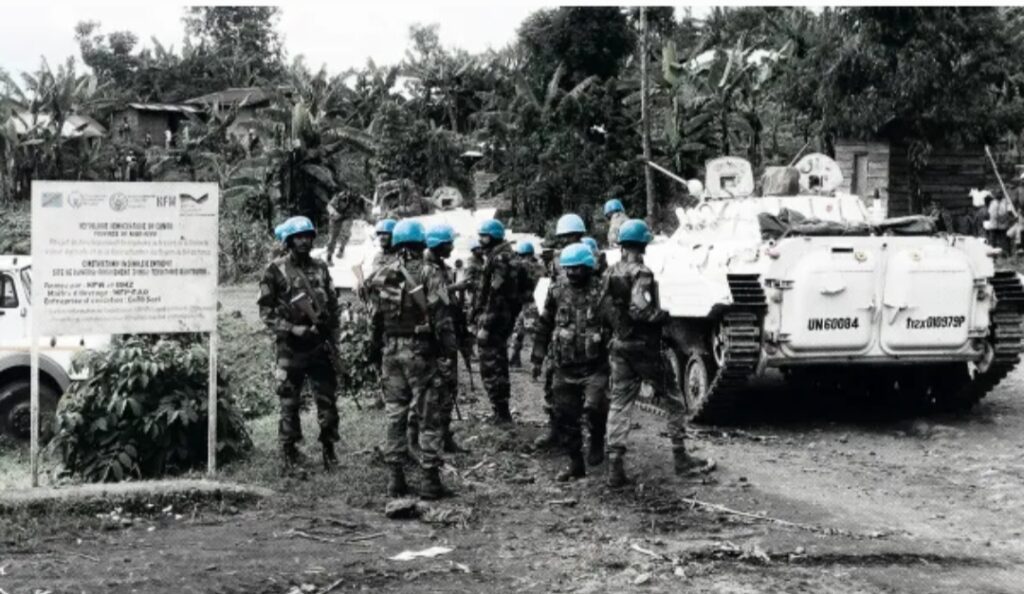

Claude Sengenya/TNH

The road leading to the Nzuma neighbourhood where community leaders say there are dozens of women and girls with peacekeeper-fathered children.

Insufficient support

The Beni region – which The New Humanitarian visited in July – has been scarred by rebel and militia violence for over a decade. Large numbers of peacekeepers have deployed there, though brutal attacks on civilians have continued unabated.

The region was also the epicentre of the world’s second deadliest Ebola outbreak from 2018-2020. During this period, workers from the World Health Organization and other aid groups sexually abused and exploited large numbers of local women.

Denise, who is in her 30s, said she met a Tanzanian peacekeeper in Mavivi, which is home to the main MONUSCO camp in the Beni region, in 2016. During a months-long exploitative relationship, he would often give her money and pay for food.

After he returned to Tanzania, Denise said he gave her $300 to start a business to help her support their daughter. He then sent ad hoc payments at his own discretion – something women in similar circumstances could not count on.

“Not all women have had this grace,” Denise said. “For others, the relationship ends either when the peacekeeper realises that we are pregnant, or when he is repatriated to his country. My friends fight alone to raise their children.”

Worried the peacekeeper would abandon her, Denise said she decided to contact MONUSCO and requested a DNA test a few years ago. She said the test confirmed paternity, but state-mandated child payments were not enforced by Tanzania.

The UN has provided support for schooling materials and arranged temporary employment, but it hasn’t been sufficient, Denise added. She said she was paid to do rehabilitation work at an airport in Beni, but her contract didn’t last long.

Safi, who is also in her 30s, said she is struggling to support her six-year-old child, whose father is a South African peacekeeper. She said he initially sent money informally, but that changed when she contacted MONUSCO to request a DNA test.

“When we were told that MONUSCO was leaving, we decided to contact the disciplinary section to keep them informed of our situation and to get compensation. That’s when everything went downhill,” Safi said.

“Since [learning of the procedures], he has cut off communication, and I no longer receive anything,” Safi added. “He asks me to now refer to the disciplinary section to get everything I wanted. Life has become complicated.”

Similar sentiments were shared by Kakule Kataliko Maombi, who is the brother of a woman who had a child with a Tanzanian peacekeeper in 2014, and who then passed away in 2019 when the child was five years old.

“Many have taken samples for DNA tests, but the results have never come out. The results are trickling in and we have no one to explain to us how the process is progressing and how long we have to wait.”

Maombi said MONUSCO previously provided the child with medical care and paid for their school fees but that it all ended suddenly, leaving his family with a “heavy burden”.

“Let them commit to just taking care of the studies of these children,” Maombi told The New Humanitarian when asked what he wanted MONUSCO to provide. “That can relieve us.”

While some women who have had their DNA tests confirmed are yet to receive formal child support, others are struggling to even get clarity on the tests and paternity claims, according to Denise.

“Many have taken samples for DNA tests, but the results have never come out,” Denise said. “The results are trickling in and we have no one to explain to us how the process is progressing and how long we have to wait. My friends are living with impatience.”

According to the UN database, of the 188 paternity claims raised in DRC since 2010, only 21 have been validated. Over 100 claims remain pending, some after many years, while the remaining claims were unsubstantiated.

Power imbalances

On top of medical, psychosocial, legal, and education support, Lo said MONUSCO provides assistance to survivors of sexual abuse and exploitation through a UN trust fund that was established in 2016.

Lo said trust fund projects – which include vocational training, livelihood support, community-based initiatives, and assistance for schooling to children fathered by UN personnel – have had a “significant” impact on the lives of survivors.

“Poverty forces our sisters to tolerate these cases of abuse.”

Still, community leaders who spoke to The New Humanitarian echoed the frustrations of the women and relatives of peacekeeper-fathered children, and also called on MONUSCO to provide more support.

Gervais Makofi Bukuka, head of the village of Vemba-Mavivi, said he is aware of more than 70 children born to peacekeeper fathers. He said most are living “without assistance”.

“They have no access to medical care, schooling, or child support,” Bukuka said. “We have alerted the section responsible for discipline within MONUSCO more than once, but there has been no significant progress. We fear for the future of these abandoned children.”

Asked why peacekeeper abuse and exploitation is so rife in Beni, Bukuka mentioned poverty in the area as the main explanation. “Do you expect resistance from a young banana seller to whom you show a 100 dollar bill?” Bukuka said.

“Poverty forces our sisters to tolerate these cases of abuse,” added Josué Kapisa, a community leader from the Nzuma neighbourhood of Beni town. Kapisa said he is aware of more than 30 children in his area that were born to peacekeeper fathers.

Unreported cases

Asked how extensive sexual abuse and exploitation by peacekeepers has been in the Beni region, Lo said MONUSCO has recorded 40 allegations over the past six years, with all them reported to the public UN database.

Lo said the mission has strengthened efforts to prevent sexual misconduct by holding contingent commanders accountable for enforcing strict discipline, and by holding regular training programmes on misconduct prevention.

Lo said UN police conduct patrols to see if peacekeepers are visiting prohibited areas or have unauthorised passengers in their vehicles, while a conduct and discipline team carries out risk assessment visits to areas where the risk of misconduct is higher.

Interviews conducted by The New Humanitarian, however, suggest peacekeeper sex abuse and exploitation has been rampant in Beni for many years, with the vast majority of cases not reported to the mission.

Several residents said bars and brothels have sprung up around UN bases, and that some have been named after towns from the peacekeepers’ home countries. Their accounts are supported by recent media reports based on MONUSCO documents.

“They leave their bases and come to enjoy life with us at night before returning early in the morning,” said Denise, who regularly works in a brothel nicknamed “Soweto” after the South African blue helmets who allegedly frequent it.

Kapisa, the community leader from the Nzuma neighbourhood, said sexual abuse and exploitation is so rife that local residents often use a Kiswahili phrase that translates as “their job is only to impregnate” when talking about MONUSCO.

Several interviewees said peacekeepers bribed the families of survivors to pay for their silence after incidents of abuse and exploitation. As a result, it became difficult for civil society leaders who were trying to uncover and document what was happening.

“When we reported these cases of abuse, the victims’ parents got [angry with] us because they were content with the material interests they got in return,” said Zadock Kamabu, a civil society leader in Beni.

“The peacekeepers could offer them chickens, rice, canned fish, or other things that they find hard to find in this area plagued by poverty,” Kamabu added. “And the peacekeepers take advantage of this misery to abuse our children.”

Kamabu said women often feel they cannot report abuse and exploitation because they do not know the names of the perpetrators. He said many would obscure their identities by detaching name tags, or using false names in front of women.

Papy Kasayi, a youth leader from Beni, called on MONUSCO to fully “settle” with women who have suffered sexual abuse and exploitation before completing its disengagement.

“They have had children with our sisters – it is important that they settle before they go, to avoid leaving us with problems,” Kasayi said. “What will become of these children without a father?”

This article was first published by the New Humanitarian: