Reporter’s diary on Darfur’s neglected refugee crisis

‘I have visited Chad three times since the start of the war and I have seen that the humanitarian response has barely improved.’

By Hafiz Haroun

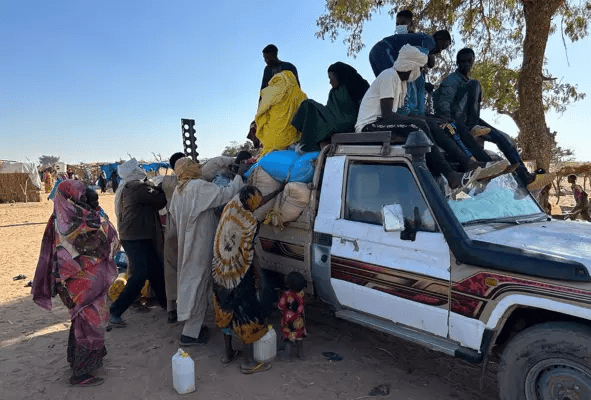

Hafiz Haroun/TNH A vehicle is loaded with goods at Ourang refugee camp in eastern Chad. Half a million Darfuris have been driven into Chad by the Rapid Support Forces, the paramilitary group that has been fighting Sudan’s regular army since April 2023.

Seven months ago, at a crowded hospital in eastern Chad, I met a Darfuri man called Jumaa. His wife had just been killed, his children were sick, and he was struggling to get food in a swollen border town that had morphed into a refugee camp.

Last month, I returned to the same camp hoping desperately that things had changed. Yet I met Jumaa in the same thatched grass makeshift shelter, unable to access humanitarian assistance despite the growing needs of his young family.

Jumaa’s situation is typical of the roughly half a million Darfuris who have been driven into neighbouring Chad by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the paramilitary rebel group that has been fighting against Sudan’s regular army since April 2023.

I have visited Chad three times since the start of the war – which has displaced eight million Sudanese overall – and I have seen that the humanitarian response has barely improved. There is little food, inadequate shelters, and not enough medicine.

Each time I visit the camps, there are also new stories of massacres and abuses committed by the RSF. Most recently, I have found evidence that civilians are being kidnapped and forced to labour on farms belonging to the paramilitary fighters.

Like in so many conflicts, women and girls are suffering the most. Some were raped in Darfur by RSF fighters and are now giving birth in the camps. Others have endured horrific sexual abuse since crossing into Chad, and have received almost no assistance.

Documenting this neglect as a Sudanese journalist from Darfur has been difficult. I think of cases like Ukraine, where refugees were given food and shelter. Why in this case are Sudanese left to die and treated as if they are not even people?

The neglect has pushed many refugees to stop counting on the international community. That includes aid groups, media outlets that barely cover the crisis, and the international institutions that have let down Darfuris for decades.

Instead, refugees are depending on themselves and on each-other. I think of the Darfuri teachers who have started schools in Chad, refugee doctors who have opened clinics, and businesses-minded people building restaurants in the camps.

Still, there is no future for the refugees in Chad, even if humanitarian organisations suddenly have more money to spend. What Darfuris and all Sudanese need is genuine peace and to be able to return to our sorely missed homes.

‘Everybody has a gun and militias are everywhere’

Reporter Hafiz Haroun high-fives a child living in Adré camp. Hafiz has visited Chad three times since the start of the war, but says the humanitarian response has barely improved.

Most of the refugees in Chad are from West Darfur state and are members of the non-Arab Masalit group. They have a long history of being targeted by the RSF, which evolved from the Janjaweed Darfuri Arab militias created in the early 2000s.

Conflict erupted last year when RSF fighters and local Arab militias began attacking Masalit areas in West Darfur’s capital, El Geneina. Some 15,000 civilians were reportedly killed between April and November as the RSF committed alleged ethnic cleansing.

Most refugees fled from El Geneina to the Chadian border town of Adré, where they were supposed to get refugee registration cards and move on to newly constructed camps or to older settlements built during the 2000s conflict.

But these camps have limited capacity, and refugees have to fight for weeks or even months on end to receive their cards. Many therefore remain stuck in Adré, where children are dying of malnutrition and adults are succumbing to treatable diseases.

When I last visited Adré in December and January, I saw people queuing all day to get food from aid agencies. Community leaders told me that thousands of refugees had not been getting any assistance, while those who had received aid got next to nothing.

Meanwhile, local authorities won’t let unregistered refugees travel outside of Adré without paying a fee. This prevents people from meeting family members and friends, and hinders their ability to find work or visit hospitals outside of the town.

The humanitarian situation is so bad that some families told me they have tried to return to El Geneina, either to gather crops from their farms or to see if the situation has improved. Unfortunately, many have not lasted long.

“Everybody has a gun and militias are everywhere,” said a woman who returned to El Geneina with her family but then quickly left after the RSF tried to recruit her son. “It is not El Geneina anymore but another town. We cannot go back there.”

Sexual violence in isolated camps

Those who have managed to leave Adré for newly built camps are given plots of land and better shelters. But the settlements are isolated, have no internet and phone connection, and lack basic infrastructure.

Residents say they are also insecure. At a recently opened camp called Ourang, hospital officials told me they had recorded 14 cases of rape perpetrated against refugee women and girls by local men between August and December.

I arrived at Ourang the day after a 13-year-old girl had been raped by three men from a nearby village. I was guided to her family house, where she was sitting inside, exhausted-looking, and with pieces of damp cloth covering her head.

“We are no longer able to stay here because our daughters are facing these constant risks to their lives.”

Her father told me she had been working at a tea stall in the camp when three locals attacked her and pulled her onto a motorbike. They transported her to an open area outside the camp and took turns raping her until she fainted, the father said.

“They have destroyed my daughter and disgraced us,” the father told me. “We are no longer able to stay here because our daughters are facing these constant risks to their lives.”

When I asked the father about the perpetrators, he said one of them was the son of a local leader. The son was arrested by the police after the attack, the father added, but was then released after paying a fine of roughly $100.

Ourang residents face other risks too. At least two people were killed by unknown local assailants in recent months, and there is a fear that the RSF will send Chadian Arab militias to attack Masalit community leaders.

It is true that local authorities have done a lot for the refugees, and it was Chadian communities that were feeding people last year in some areas before the big aid agencies arrived. But there is still clearly a need for much better protection.

Despite that need, I saw just two police officers at Ourang, and neither of them were armed. As a result, some camp leaders and residents said they were thinking of leaving. “We cannot stay here,” an elderly woman told me. “It is not safe.”

RSF crimes: ‘We were killed 20 years ago, and we are still killed today’

Each time I have visited Chad, people have been dealing with new episodes of violence. During my latest visit, daily conversations were largely focused on an RSF massacre carried out next to an army base in Ardamata, a suburb of El Geneina, in November.

According to my reporting, and research by other journalists and rights groups, hundreds, possibly thousands, of Masalit were killed in Ardamata by the RSF, which accused the community of supporting the army.

The stories that I documented from refugees who fled Ardamata are horrifying, and many camp residents told me they are still looking for missing relatives and friends. Some have even ventured back to El Geneina to try and find news.

While walking around the market at Adré camp, my eyes fell upon a seven-year-old Masalit child who was begging for food. Both of his hands had been burned and he was missing his fingers.

The boy’s mother told me that RSF soldiers had entered their house in Ardamata and accused the family of hiding weapons. She said they killed her husband and then held her son’s hands over a cooking fire for several minutes.

The trauma of Ardamata continued long past November for survivors like Adam Haroun Ali. He is one of many Masalit youth who were taken captive by the RSF and sent to Arab communities, some distant and remote, to work on farms and in homes.

“We can benefit from him,” Ali recalled an RSF commander saying of him amid the scenes of carnage in Ardamata. “We will let you live in exchange for working on my farm,” the militiamen added.

Ali told me that he worked for three weeks harvesting peanuts from dawn until dusk on farms belonging to the RSF commander’s family. After the crops were cultivated, he was finally released and able to join his family in Chad.

Many Masalit see these crimes as a continuation of the violence of the 2000s, when Janjaweed militias were tasked by then president Omar al-Bashir to put down a rebellion by non-Arab groups, who were protesting against Darfur’s marginalisation.

During their counterinsurgency campaign, the Janjaweed slaughtered thousands of non-Arab civilians, including Masalit, and occupied their land, creating deep divisions that were never resolved.

“We were killed 20 years ago, and we are still killed today,” a Masalit refugee called Ali Adam told me. He said Darfuris had been abandoned by the international community and that ongoing cases at the International Criminal Court were no cause for hope.

Three stories of perseverance

Despite the trauma that Darfuris have experienced, I have documented many stories of individual perseverance, stories about those who escaped the violence and about those who are trying to rebuild in Chad.

In Ourang camp, for example, I met a 20-year-old man who said he was part of a group that collected and buried more than 100 bodies in Ardamata before escaping to Chad under RSF gunfire.

The man is now working with a local Masalit organisation, documenting the killings and counting those still missing. His group visits new arrivals from El Geneina and asks them what they have witnessed and if they can confirm who is alive or dead.

I also think of the woman whose son had his hands burnt by RSF troops. She told me she had nursed him for two days using chia seeds and other local medicine even as she was full-term pregnant with twins.

In the hardest of circumstances, the woman gave birth to the twins in an abandoned house in Ardamata. She then finally escaped to Adré, where her family now lives in a tatty shelter with a roof made of their own old clothes.

Finally there is Jumaa, who I mentioned at the start. His wife was killed by an RSF-aligned Arab militia on the road from El Geneina to Adré. He carried her on his back until she died, at which point he was forced to leave her by the side of the road.

Jumaa said losing his wife was “the most difficult moment” he has ever experienced, yet he is not interested in revenge. He told me his new focus in life is to fulfil his wife’s final wish: that he dedicate himself to their children.

“I am determined to make my children happy because that was the last request from my wife,” Jumaa told me. “She said: ‘I leave you my children, you are responsible for them now, you have to fight for them’.”

This article was first published on The New Humanitarian: