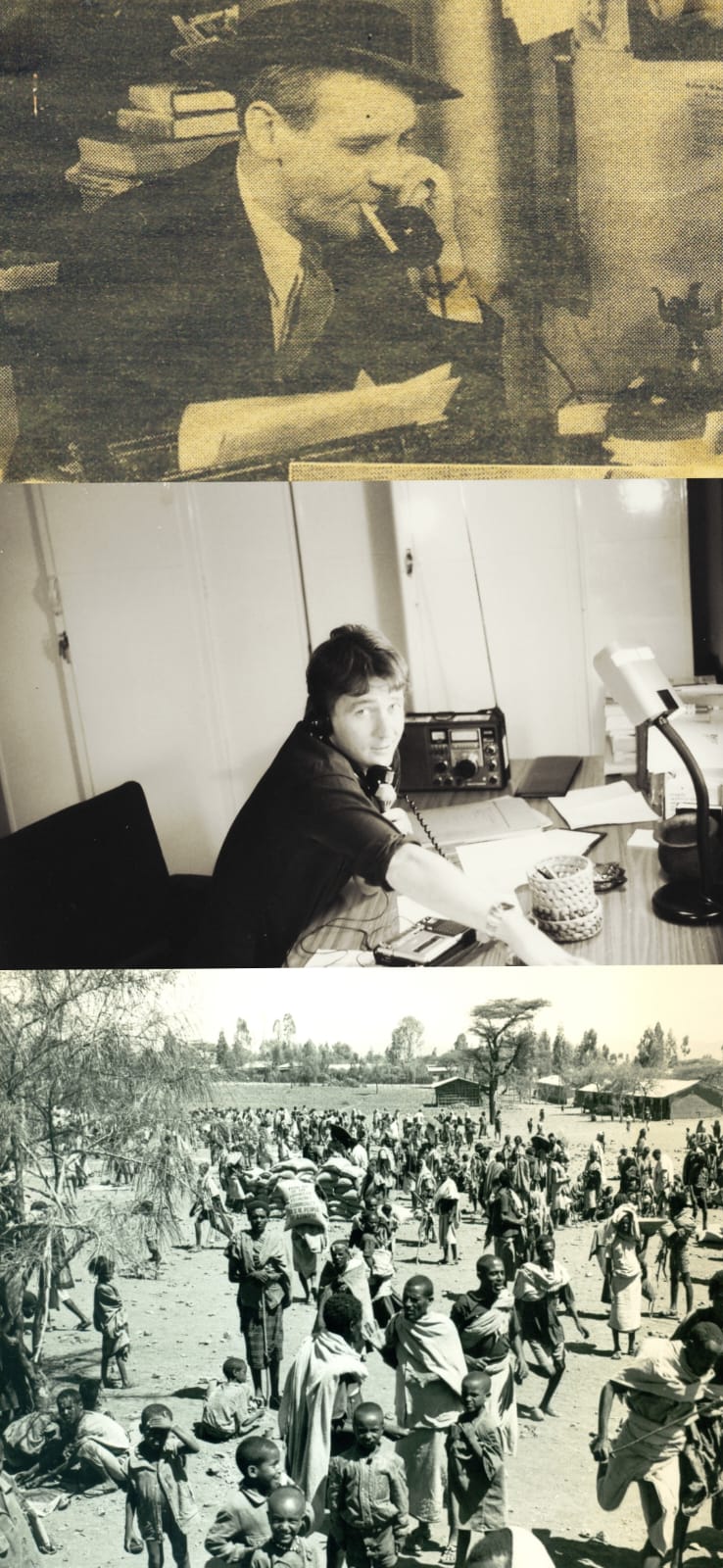

Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

A muffled bang at a remote lake in western Cameroon in August 1986, followed by a rising wind, then soon after, hundreds of dead animals and people litter the valley. The cause and extent of the disaster are unknown. Rescue teams equipped with gas masks are the first to reach the area. No journalist can get near the place.

Four days later, the AFP news agency, citing an interview with an expert, reports that Lake Nyos has probably exploded, spreading a deadly amount of carbon dioxide across the valley. Five days later the Red Cross arrives with body bags. There is no instant news, because this is before the era of cell phones, internet, satellite photos. The media has to wait until opportunities arise to travel to the area to reveal the mystery. It takes a week for the first camera crews to fly in by helicopter.

Fast forward 37 years. In many newsrooms early last month, a feeling of disbelief, perhaps disenchantment, prevails when unclear reports come in about the gigantic destruction in Derna; 24 hours later, the Libyan city is still inaccessible. There is a big difference between this and the other disaster that had occurred a few days earlier in the same region. The magnitude of the earthquake in Morocco was immediately clear. Because there were images of Morocco, but not of Libya. We have become consumers of images. If it is not etched in our minds, we cannot comprehend the disaster.

Rwanda 1994. In the morning hours my radio world receiver reports something about an air disaster near Kigali in which the presidents of Burundi and Rwanda have been killed. The afternoon edition want a story, which must be written immediately. I speculate that the consequences will be disastrous, particularly for chronically unstable Burundi. In the days that follow, a completely different scenario unfolds: it is an internal Rwandan matter, the downing of the plane the starting signal for a genocide in Rwanda, in which approximately 800,000 people will die in three months.

Nigel Barley wrote in 1983 in his The Innocent Anthropologist: “The fieldworker can never hope to maintain a good pace of work for long. In my time in Africa, I estimate that I spent perhaps one percent of my time doing what I actually gone for. The rest of the time was spent on logistics, being sick, being sociable, arranging things, getting from place to place, and above all, waiting.”

For a correspondent, too, ‘getting there’ takes the vast majority of his time, much more than researching and writing an article. And what he will find will remain a secret until the very last moment. So, take your time, turn a minute into an hour, an hour into a day, a day into a week. Otherwise, frustration follows, as Barley wrote: “I had defied the local gods with my intemperate urge to do something. I would soon be cut down to size.”

In 1994, after a long detour through Uganda, I arrive in the empty Rwandan capital Kigali. The telephone connections no longer work. Only as I travel further into the countryside do I grasp how, in a methodical pattern extremists from the Hutu majority are carrying out a genocide against Tutsis. Maybe, just maybe, if mobile telephony had existed then, the fury wouldn’t have spread unhindered from one hill to another like a forest fire. If images had come out immediately, a genocide could have been stopped. But the power of the image was missing.

On my travels I used to be alone and inaccessible. Traveling and reporting were an adventure. When I reached a big city, I handed typed documents or tapes for a radio report to a KLM stewardess. These were then picked up at Schiphol airport by someone from my newspaper or radio station or sent by post from there. It took days for my reports to be published in the Netherlands. And no one minded, because Africa was far away. Telex was the fastest and most reliable means of communication.

Africa’s first major post-independence war was in Nigeria, which left more than a million dead when the Ibo, one of Nigeria’s three largest population groups, attempted in 1967 to establish an independent Biafra. That became the first television war: images of blood, intestines and severed limbs flooded into living rooms all over the world every evening. It heralded the beginning of the charity industry: Jean-Paul Sartre and John Lennon protested, Joan Baez and Jimi Hendrix played for a benefit concert and medical activists founded Doctors Without Borders.

The link between image and response was strikingly demonstrated in Ethiopia. An estimated one million people died in the great famine in Ethiopia in 1984. But initially it was just conjecture. These were the waning days of the Cold War and the heyday of that right-wing duo Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom. The Ethiopian Marxist dictator Mengistu wanted to keep the hunger hidden and so for months journalists were not allowed to enter the affected area. Until Kenyan cameraman Mohamed Amin came up with images that shocked the world and spurred it to action. Mengistu eventually opened the country to journalists to gain publicity for aid from the West, but by then Prime Minister Thatcher and President Reagan did not want to cooperate.

Musicians took action. Bob Geldof and fellow musicians sang “Do they know it is Christmas” in 1985 in London for Live Aid. In New York Harry Belafonte mustered a group of stars, including such legends as Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson, Bob Dylan and Lionel Richie, who sang together “We are the world”. The artists raised money for the hungry Ethiopian people. Modern mass media, the combination of television and the music industry, overcame the hypocrisy of the cynical Cold War years and ensured that a large-scale aid campaign was launched. It showed the power of popular feeling.

After the emergence of 24-hour news channels such as CNN in the late 1980s, cameramen and sound technicians joined the foreign press corps based in Africa, which until then had consisted almost entirely of writers. They had money and their presence became essential if disasters were to get publicity. Only with tv images did the disaster receive attention in the West, after which relief efforts were initiated. Chartering a Boeing 737, CNN flew recording and broadcast equipment into the desert of eastern Ethiopia, where it broadcast from Somali refugee camps in the late 1980s. Secretly, the producers hoped that someone would die during the live broadcasts. Dying live: the ultimate.

And now Sudan. It’s barely on the map. A disaster of epic proportions, the United Nations warns, but it is a calamity behind closed doors. There are no images of the ethnic cleansing taking place in Darfur, only the horror stories of the victims who moved to Chad. No images of Khartoum’s desperate residents of Khartoum who have been living with water, and food shortages- and no safety for six months. It’s too dangerous for reporters.

The conflict in Sudan follows an even bloodier battle in Tigray, in northern Ethiopia, where the government hermetically sealed off the area so that large-scale war crimes could be committed unhindered by cameras. Autocratic regimes are applying media policy increasingly effectively. A battle has been going on in the English-speaking part of Cameroon for years, but President Biya manages to keep the press out, and so the conflict never reaches the international agenda. Because our compassion can only be stirred by intense images.

This article was first published in NRC on 25-9-2023