Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

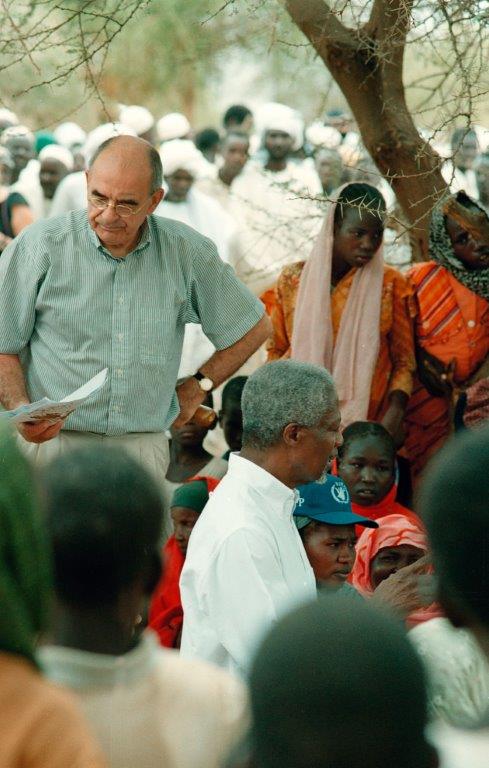

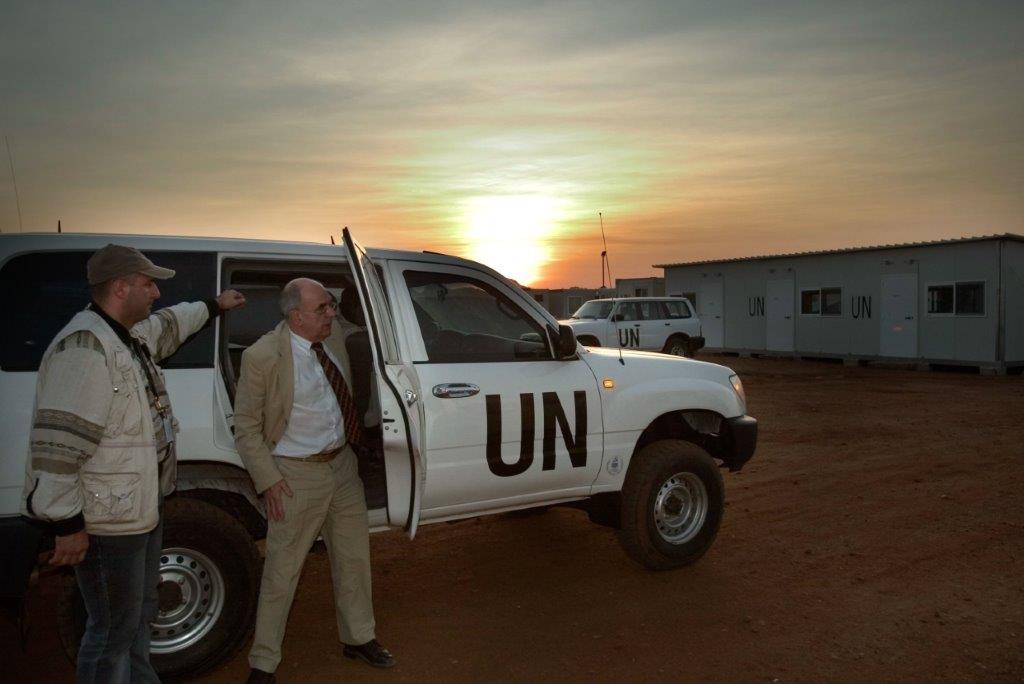

Jan Pronk, a Dutch politician and diplomat born in 1940, dedicated his life to helping the vulnerable through many years of significant international service. That moral commitment dating from era in the last centuary, makes him like look like a ventriloquist from another civilization.Serving as the Dutch Minister of Development Cooperation during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, and later as the UN Special Envoy to Sudan starting in 2004, Pronk positioned himself in the midst of global conflict areas. Motivated to support victims, he traveled extensively across the Horn of Africa, facing tough journeys on rough roads and flying in old planes to meet with both guerrilla leaders and government officials, all to provide food aid and work towards peace.

His missionary enthusiasm sharply contrasts with today’s political environment, where selfish interests have replaced global engagement. A stark modern example of this neglect is the over five-hundred-day siege and starvation of the medium-sized city of El Fashar in Sudan, facing the looming threat of ethnic cleansing. While significant relief efforts were typical during Pronk’s time, this ongoing disaster has hardly sparked any international outrage. The situation has worsened to the extent that even talking about “an intervention to safeguard humanitarian convoys to El Fashar is currently impossible,” as no one is willing to bring it up within the UN framework.. Because they’ve been dismantled,” says Pronk. His book, “Scheuren rond de Hoorn van Afrika” (Fissures Around the Horn of Africa), was published in September by Walburg Pers, part of a series of books about his time as minister.

The world is divided, and as a result, the United Nations no longer functions?

“The UN is weak because the world’s three major powers are competing for spheres of influence. That wasn’t the case in the 1990s, when there was unity in the UN Security Council. Now, some major powers have an interest in continuing the war. At the time, I operated in a favorable geopolitical situation, because after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, neither East nor West was interested in expanding their political influence. This allowed for many changes in Africa. That’s behind us now. A third major power factor has emerged: Islamic extremism. And a fourth: that of Big Tech, Big Finance, and Big Pharma, which control governments and markets, making it virtually impossible for governments to steer the economy.”

In his book, Pronk criticises the leaders in the Horn of Africa of his era. He asserts that they offered little more than lip service to the concept of peace. He writes: “Development was equated with personal profit, the right to protection applied only to one’s own group, humanity was denied to opponents, while human rights were not seen as an absolute and indivisible concept but as an export product of the West.” Pronk was quick to hold those rulers accountable, even if it seemed patronizing or like Western meddling. Back then, many nations were struggling; now, governments are more confident and less open to that kind of interference.

You didn’t always agree with Western demands, you write. Yet, Africa had to listen to the demands of the white man. Whether they came from Washington, Paris, London, or The Hague.

“At that time, I organized conferences on Africa. African leaders participated and criticized the West, and that was my intention. In this century, however, the West has become extremely arrogant. Now Africa is again seen as a colony. The West essentially left Africa with its tail between its legs, because we pursued a rather hypocritical policy. This included economics. And because we failed to respect human rights in any balanced way. Human rights for white Europeans, not for Africans. That’s what’s being seen in Africa. Meanwhile, the influential Western role has been taken over by Russia and China.”

Your successor in the Netherlands wanted nothing to do with the record you’d built up. Then-Prime Minister Wim Kok didn’t approve of your activist approach either. And European ministers are not very concerned with Africa, you say in your book. Is it true that the European left has little interest in Africa?

“Unfortunately, the European left is very self-absorbed. The narrative is mainly about putting up barriers by working together effectively among the left and becoming stronger against the undemocratic right. That’s what all these political debates are about. They focus on migration and asylum, among other things. And on discrimination. That’s the current culture war. In the 1970s, the left was much more concerned with the Global South.

Just read the Labour Party’s party platform. It’s a fine platform, mind you, but all its priorities relate to the Netherlands. My major political debate has always been that when you talk about solidarity, which is the core of a social democracy, that also applies to people across the border. They are often worse off because of us, because of our colonial past. But also because of our neocolonial actions.”

In the book, you mention several benchmarks: no white supremacy, lower greenhouse gas emissions, less competition for raw materials, and less material economic growth. And fewer obstacles for refugees. Such a program won’t get you far in Dutch politics.

“No, not in the Netherlands. But I will continue to fight for it. To put an end to post- and neocolonialism, which are a precursor to racism. We really need a reversal of international policy. That is also in the interest of the Netherlands and Western Europe. If we don’t do that, we will lose our credibility, which we’ve almost lost anyway.”

Pronk recently reacted strongly to the deal announced in October between the Netherlands and Uganda to send migrants to Uganda. The former minister observes how African interests are consistently subordinated to European agendas.

“A game is being played with Africa again for the benefit of domestic politics within European countries. The idea of sending people back across the Mediterranean, regardless of their origin, is shortsighted, without considering the real reasons why people migrate. It’s pure hypocrisy.”

THE LEADERS

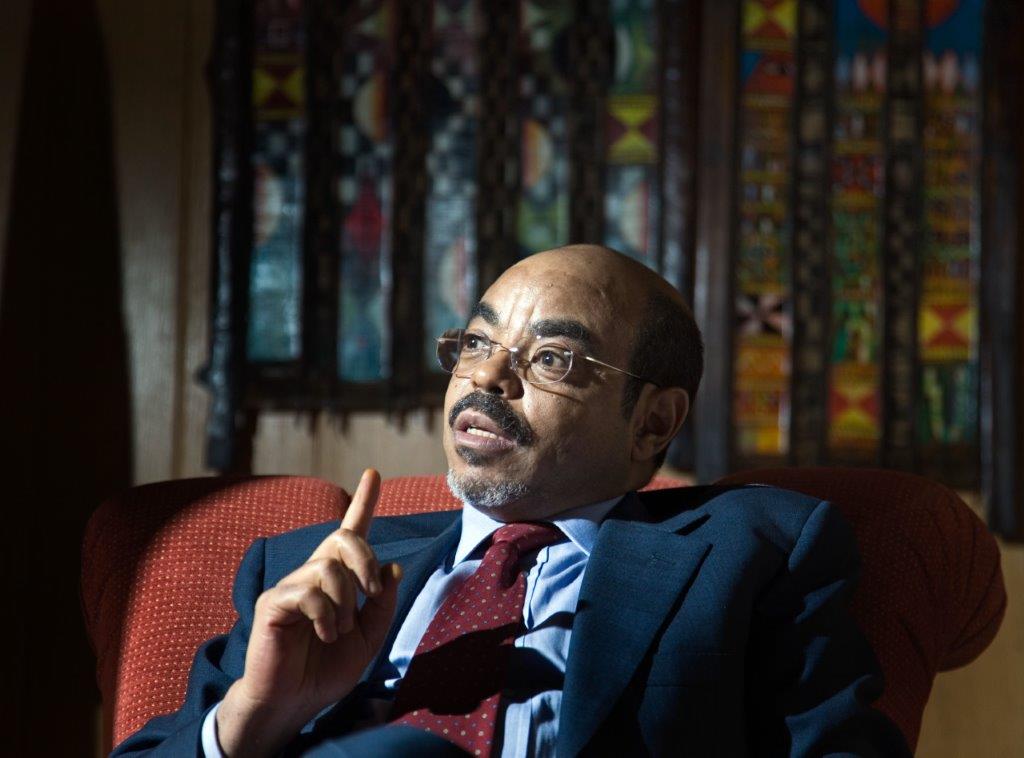

In 1991, the guerrilla movement of Meles Zenawi seized power in Ethiopia. Pronk and the intellectual Meles were a match for each other. They spent hours debating developments in Africa. After Pronk became a professor at the Institute for Social Studies in The Hague, Meles graduated under his supervision with a thesis on the Ethiopian model of governance. He then planned to pursue a master’s degree with a dissertation on human rights and democracy.

Pronk met with the leaders of Ethiopia and the one of Eritrea, Isaias Aferwerki, many times. “I had respect for him,” says Pronk of the then-Ethiopian leader Meles Zenawi. And in his book, Pronk writes: “Meles had an inexhaustible knowledge of African history and a great interest in economic developments. He always spoke knowledgeably, approached problems from different perspectives, and understood nuances, but ultimately always remained decisive.”

“Meles and the Eritrean leader Isaias Aferworki had close family ties; they addressed each other as ‘cousin.’ Isaias was much less thoughtful than Meles. He quickly took a position and was not easily dissuaded. Meles remained the same throughout the years I knew him. Isaias did not. Initially, Isaias was warm and jovial, later withdrawn, bitter, and paranoid. Then he saw enemies everywhere, he developed into a despot, and had no mercy for those who opposed him. Isaias debated with his visitors with the sharpest of wits; he could listen, but never conceded. Meles had thought deeply about things. His view aligned with mine: too many developing countries had been pressured by the IMF, the World Bank, and Western donors to do the bidding of transnational corporations and banks under the guise of “good governance.”

“Stubbornness had played a major role on both sides. I had come to know both Meles and Isaias as independently minded and self-reliant political leaders, capable of distancing themselves from their own party elite. However, Meles apparently became entangled in a web of political interest groups in his own country, while Isaias couldn’t free himself from self-importance, self-righteousness, and the feeling that the whole world was against him.

“Unlike Isaias, Meles’s personality seemed to guarantee enlightened policy: wise, upright, and dedicated. He had a deep understanding of the dynamics in his own country and in the surrounding countries. Moreover, Meles set the right priorities: improving the plight of poor small farmers and curbing the power of foreign capital. He wasn’t out for personal gain, enjoyed discussion and debate, and continued to study. He was far from always successful in de-escalating domestic conflicts and was dependent on the cooperation of former comrades who held positions of power in the region. But he genuinely tried to prevent his regime from overstepping the mark.

“But that’s what happened in 2005 however, when he had people shot dead in the streets of Addis Ababa. It was such a sad event that I didn’t want to see him again. He was the one who truly wanted democracy in society, but suddenly he saw his position threatened after the elections. Years later, in July 2012, the Ethiopian ambassador to the Netherlands told me that Meles was seriously ill and hospitalized in Brussels. Meles hadn’t asked for me, but the ambassador told me he was sure he wanted to see me. I hesitated and postponed a visit. Then it was too late. I still regret that.”

From Minister and UN Envoy to Persona Non Grata

CV of Pronk:

Johannes Pieter (Jan) Pronk (born May 1940) served as Minister for Development Cooperation for the Labour Party (PvdA) in three cabinets: 1973-1977 (under Prime Minister Den Uyl), 1989-1995 (under Lubbers), and 1995-1998 (under Kok).

Pronk was appointed UN Special Envoy for Sudan in 2004, where ethnic cleansing was taking place in Darfur. Two years later, the Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir declared him persona non grata.

Parts of this interview were first published in NRC

Pictures by Petterik Wiggers