By Richard Dowden

Telling Africans and their leaders what to do – or not do – is not in my nature. Outsiders do not have a good record in this area.

But sometimes situations and events become so precarious and decisions taken are so obviously going to lead to disaster that you have no choice but to say something. This is Africa’s moment and the world is slowly but surely recognizing that the continent is no longer all about dictators, tribalism, wars and corruption. But some presidents – throwbacks to the age of dictators – are threatening this new perception.

When Thabo Mbeki was President of South Africa, he cast doubt over the accepted wisdom on HIV/AIDS. South Africa was pilloried and rightly so. But many South Africans quietly got on with combatting the spread of the disease. One of them was Jacob Zuma, the Deputy President, in charge of the national Aids project. In an interview I did with him in 2002 he quietly dissociated himself from his president’s views on aidssaying: “…what has happened is that people have mixed the president’s thinking with the policy of the government… he is a thinker, a political scientist… government policy is based on the premise that HIV causes Aids.”

Later however, he admitted that he had sex with a woman who was HIV positive but took a shower afterwards. Perhaps he did not really believe in the campaign he had headed after all. At his recent re-inauguration the President did not look well. He has had to cancel so many engagements and meetings that it is now clear that Cyril Ramaphosa is running things. Since being open about one’s HIV status was one of the main policies of his government’s anti Aids strategy, it would be a great act of leadership for President Zuma to now declare his own status.

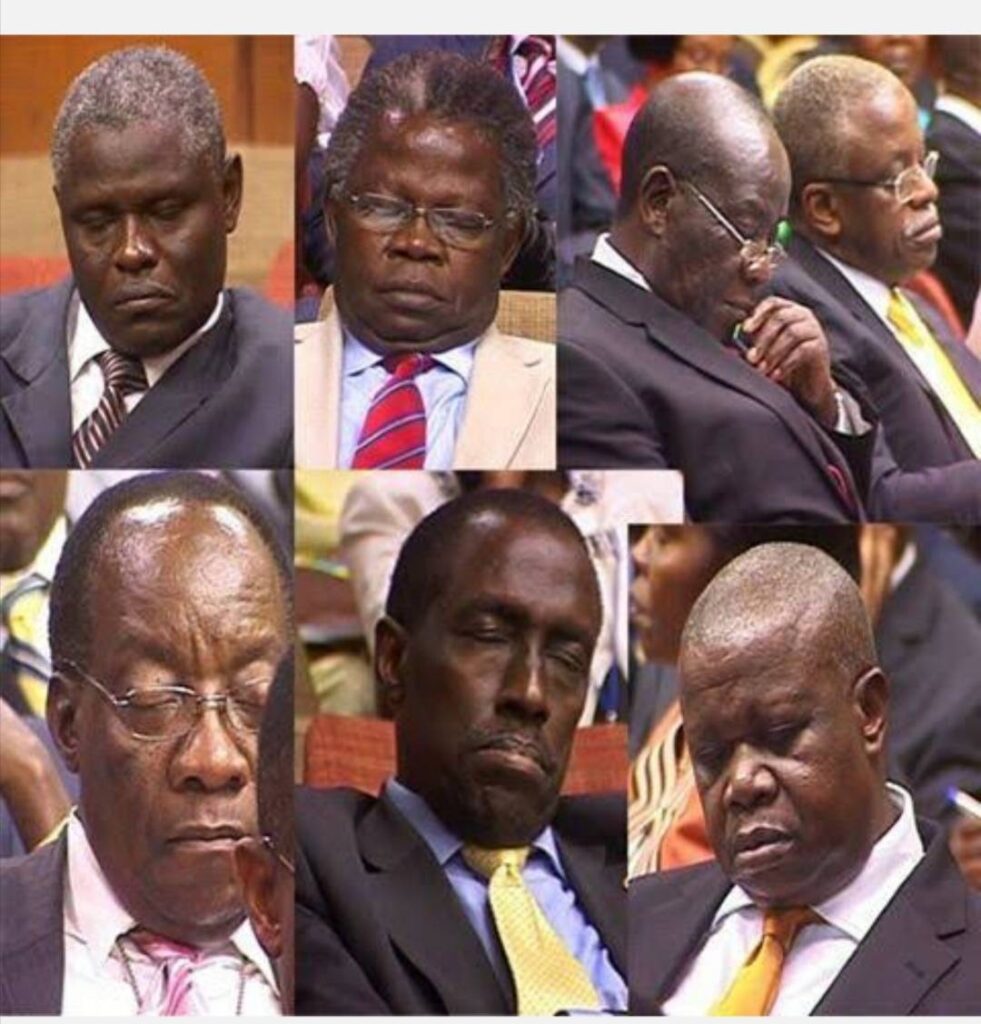

Three other presidents seem to be in denial about the inevitable future of all human beings. These are Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, 70 and now in his 28th year as president, President Michael Sata of Zambia, 77 and, of course, President Robert Mugabe, 90. Meanwhile Algeria has re-elected a 77 year-old who has been the country’s leader since 1999 and has apparently not been seen in public since his inauguration.

Having just passed a significant date myself, I am quick to say there is nothing wrong with being old. But the questions good leaders must ask themselves are first: can I still do a good job? And second: who will succeed me?

Zambians are telling me that Michael Sata is unlikely to return from hospital in London, which could mean that Zambia, in Guy Scott, will have a white president. Whoever it is, Zambians – renowned for their profound tranquility in troubled times – are likely to find a good enough candidate. The show will stay on the road.

Much more worrying are Zimbabwe and Uganda. I wonder if in 30 years time historians will agree that the failure of leaders to step aside at the right moment was the reason these countries were plunged again into chaos. Let’s hope it does not happen, but if it does the culprits will be Mugabe and Museveni.

Mugabe has already done his worst: destroyed the country and cowed the people. I cannot see Zimbabweans rising up en masse when he dies. The war will be between his cronies.

Museveni, at one time an open-minded, dynamic, intelligent leader who once said that African leaders stayed in power too long, has become paranoid and hides away. He has tried to position his son and even his wife to succeed him, but it is clear that the people of Uganda will not accept this. Anyone else who tries to make a bid to become his successor is cut down. He moves around the country dolling out wads of cash from a bag (where does the money come from? His own salary? Don’t ask.)

His once faithful Prime Minister, Amama Mbabazi, also in office for more than 30 years, is being harassed for trying to position himself for the top job. He is also deluded. The time for all of them has passed.

For the first decade after he came to power in 1986 Museveni got southern Uganda moving again. The north remained undeveloped, much of it a war zone, until the last few years. Since then the entire country has become increasingly corrupt, tribal and violent. If – as looks increasingly likely – he will die in office like Mugabe, and if the anger bubbling under the surface explodes, the aftermath will be a catastrophic.

It is time for Museveni to be brave and hold a free and fair election on a level playing field. If he wins he should immediately announce a departure date in a year’s time and find an acceptable successor. If he loses he must go straight away. But I fear he is not brave enough to do this.

Recently I was driven off the Entebbe – Kampala road by a fast moving presidential convoy heralded by a phalanx of huge police motorbikes with blue lights flashing and sirens wailing. There followed 14 heavily armoured trucks and Caspirs (Apartheid South Africa’s main military vehicle designed to quell riots in the townships). There was even an enormous ambulance – though I doubt it would have stopped for the child that must occasionally have been run over by the convoy speeding at over 60 miles an hour on a narrow crowded road. Two vehicles were packed with soldiers, one in full combat gear with gas masks over their faces.

This was not far from the clock tower roundabout where 42 years ago I saw another Ugandan president. He was driving alone in an open Jeep and stopped to let us pass. He waved gaily to us even though he had just denounced the British for trying to kill him. His name was Idi Amin Dada.

I know who was the braver man.