Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Africa has developed breathtakingly fast. It now operates confidently on the geopolitical stage and escapes the assumption that it simply needs to be helped. With the freedom of the great pen stroke, with the denial of the great regional differences, that is my summary of forty years of reporting.

Africa in 1973

I would like to take you through half a century of change in Africa, of which 40 years were there for me to report on. My perception of the African world is shaped by my daily experiences in Kenya; however, my professional duties have taken me to nearly every country across the continent.

On my first trip to Kenya in 1973 I saw only a few cars on the road into town, I saw more zebra’s and giraffes than cars. Nairobi was a garden city with a little traffic jam lasting 5 minutes at the end of the afternoon, in front of rare traffic lights at the top of the Kenyatta Avenue. It was a time when you could still find a leopard in your kitchen store. Kenya was an agricultural country with hardly 13 million inhabitants, now we have between 55 and 60 million.

Nairobi 1973

Terms like Afro optimism or Afro pessimism have never been used in Africa itself, these are views given by outsiders of the continent. But it can be said that in the 70’s the general mood was positive, there was confidence.

The journalistic approach was still kind of colonial. The western mind still had to be de-colonized. Pre-conceived ideas -about Africa’s barbarity and Western charity- dominated the narrative. The western press wrote Tarzan stories: in Congo about blacks killing whites, or the other way around in South Africa. Or stories focused on the theme “the Sovjiets are coming´.

I gave myself the task to see it from an African perspective. I wanted to adapt and integrate, and travel through the souls of other people who were foreign to me. I wanted to try to enter their souls, deep into their souls, try to understand what makes them tick, what is the past that shaped their souls.

As Ellis remarked, “History matters.” The African context is characterized by communalism, ubuntu, a harmonious existence with nature, and a connection to both spirits and a god. Stephen Ellis highlighted, that without knowing faith, one cannot understand Africa. History matters, is what Ellis noted, including slave trade, colonialism, half a century of development aid and the IMF/Worldbank dictates in the 80’s and 90’s. As the American writer William Faulkner once said: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past”.

1983 IMF World bank Wars of liberation

Austerity

In 1983, two decades post-independence, the reliance on Western countries had paradoxically increased. A strict regime of austerity of IMF and World bank were in place in many countries. If governments did not have the money anymore to pay for education or medical care, then they were advised to neglect these sectors. Education and healthcare for all had been one of the major achievements of independence and now these rights were taken away. This was a horrible period and a period of general decline and implosion of states. And a mistake, as economists and strategists of that time will now openly tell you.

And as Ellis wrote: Africa inherited economies of extortion and plunder from colonial times. The liberalization of Africa’s economies under pressure from the IMF and other lenders strengthened the influence of informal networks and local mafia.

In Tigray 1990

Wars

Many wars broke out during that time, and I covered many. A chain reaction started with Museveni taking power by force in Uganda, followed by the victory of Paul Kagame in Rwanda in 1994 and Kabila’s take over in Congo in 1997. At the same time in the Horn of Africa, the SPLA fought in southern Sudan against the Arabized North and in the regions of Eritrea and Tigray the fight was on against a harsh communist regime in Ethiopia.

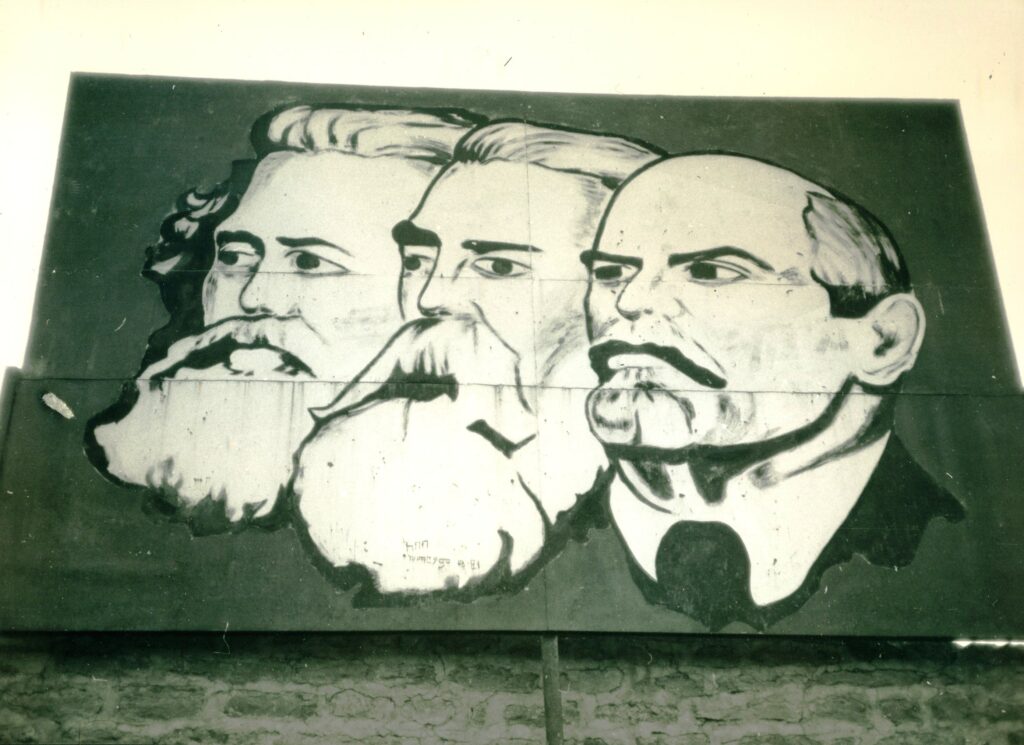

If felt out of place that in a biblical landscape in the mountains of Ethiopia I had discussions under de portraits of Marx, Engels and Lenin with student leaders who had transformed into guerrilla fighters, who had developed educated thoughts about Albanian agricultural reforms, about peasantry, about class struggles.

These were wars for liberation. They were horrible, but they had a purpose.

1993 useless wars of implosion with Charles Taylor

That ideological drive among fighters was not at all present among the fighters of the wars I had to cover in the 90’s, in particular in Liberia and Sierra Leone. These were completely different type of insurgents, they did not herald hope but symbolized the decay, they did not inspire but provoked a trail of revenge.

For example: Being with Charles Taylor in his bush camp was a hallucinating experience.

I judge a trip successful when I have learned something new. Most of my trips have been like that, and certainly the one to Liberia in 1990, to meet the rebel leader Charles Taylor.

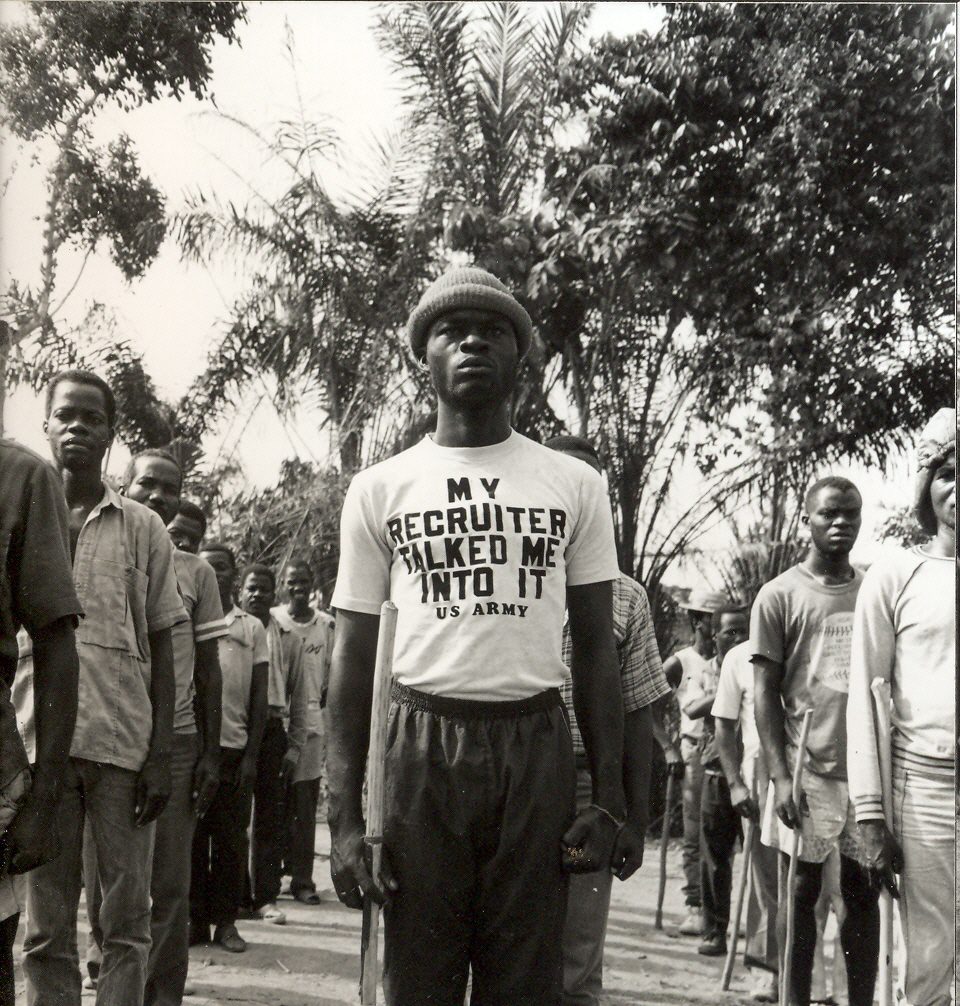

In a steaming jungle I crossed the border river on a half-submerged raft and continued my journey past largely deserted villages with skulls of government soldiers put on sticks.

As the drowsy mist lifted, the contours of a bizarre scene became clear. The hum of all kinds of activity swept over me. I saw an endless line of young recruits marching with a stick in their hands, barefoot or in broken sneakers. In small leather pouches they wore amulets around their necks. Under the influence of their warlords, they were given marijuana, alcohol, and amphetamines, leading them to commit acts of violence, including plundering, raping, torturing, and even cutting off genitals, beheading people, and sometimes even eating body parts of their victims. And they dressed in all kind of funny and female dresses and wigs.

Where did this hide and seek behavior come from? It required some empathy, but I understood the positive side of cannibalism. Because what better compliment can you get than someone wanting to eat you? Because he considers your powers and character so special that he wants to appropriate them? Please, eat me.

Writing about the centuries-old, secret communities in Liberia that shape the daily lives of everyone there, Ellis noted in a footnote of his book The mask of anarchy that Charles Taylor had also taken a bite of human flesh to strengthen his spiritual powers.

Rebels of Charles Taylor in Liberia

Multi-party Fight for pluralism

The 90’s were in every way a period of reform, either by war, or by political revolt, or pushed by outside forces in the economy.

The fight for pluralism has always been there. The political scene in the countries with a more stable political class underwent changes around 1991. Young people and younger politicians felt muzzled in the one-party state and revolted in the same way we now see Gen Z threating the political class. It is a vicious circle in a way, this struggle for more pluralism.

I could see that the desire for change was real, but also naïve. That is a challenging moment for a correspondent: should I go along with their enthusiasm or hold back and be sober.

Covering politics and elections felt like a revolution at that time, yes, it felt like liberation, as if Africa had turned a corner.

Very soon it became clear it did not make that much of a difference. Politicians now had to fight harder to win an election, and had to spend more money to bribe voters, but the ruling class stayed on top anyway. Under the multi-party system, the stranglehold on politics by the corrupt political class has not been broken. Politicians have to spend more money and make more effort to stay in power, but a new kind of less arrogant leadership did not emerge.

Kenyan Gen Z in 2024

Economic liberalization how bad was the situation, re-emergence of private sector

Maybe much more important than the politics was the economic liberalization taking place that time. I very well remember how horribly bad the situation had become in the 80’s and the 90’s. In Sudan you could not buy bread, tea leaves or sugar anymore and tea was made of onions. In Tanzania there were no bulbs in expensive hotel rooms. And going out for dinner in Maputo you had to come with your own cutlery and order 2 days in advance, so the cook could start buying ingredients for your meal.

Most economies had come to a standstill, because of bad politics, bad governance and civil wars. Drastic changes were inevitable.

At that time the term “the lost continent” and even “the hopeless continent” were invented in the western world. Of course, that derogative language, to call somebody’s place hopeless, that patronising attitude, was not being used by Africans, but by outsiders.

The most important result of these economic reforms was to the re-emergence of the private sector. The states sold off their companies, and in this process a lot of stealing took place by corrupt government officials who bought these companies at giveaway prices, this stealing contributed in no small measure to the emergence of the middle class in Kenya. But as an energetic hopeful young chap in Nigeria told me: “free market means freedom; we can participate again in the economy and that helps in building democracy”.

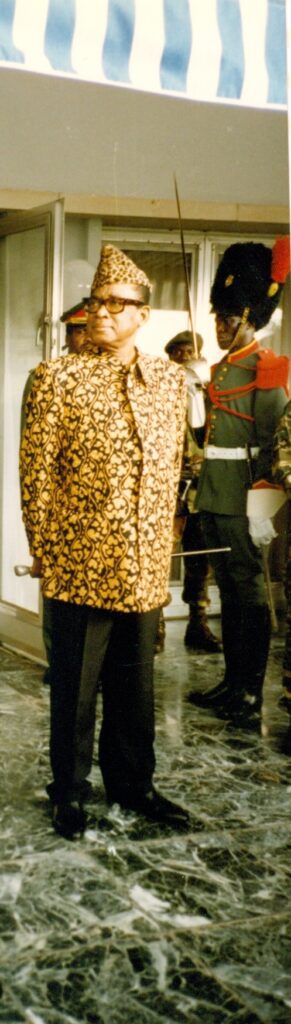

Zairean president Mobutu, just before his fall in 1997

Turn of the century Growth

Then the period of growth came. The turn of the century brought macro-economic growth, the West leaving and the East coming in with massive amounts of money did make a lot of visible changes. My friends, my family members, suddenly all had their children going to schools, people in the villages were not going barefooted anymore and universities were mushrooming.

With that image of the new prosperity in mind, people who have experienced Africa half a century ago can only conclude the continent has progressed tremendously.

If you go to one of the many new shopping malls which have sprung up over the last decades, you can buy almost everything you want, from the latest computer models and smartphone to watching the latest movies and buying the latest books. And the global fast-food companies in the meantime will make you get fat and unhealthy.

But as soon as you go out of these shopping halls, you get into the public Africa, with huge potholes on the roads, corrupt officials and a lot of crime the police won’t or cannot do anything about. Corruption has grown in all countries. That is also free market.

The problems are that this type of growth does not translate into many more jobs and industrialisation. I see too many university graduates selling posters of Bob Marley or Obama in Kenyan slums, there is simply not enough employment for the thousands and thousands new job seekers on the market.

Population growth Angola street kids, Nairobi disadvantaged areas.

Another major change is the effects we begin to see of the big population growth. Just look around you in Africa and you will notice that the majority of people around you are younger than you are.

70 percent of the population is below 30 years of age. The population growth presently taking place is unprecedented in human history. Where I saw virgin nature 30 years ago, I now see shambas, where I saw agricultural fields, I see buildings. It is doubtful whether Africa at this stage has room for all these new people. Forest are being cut like matchsticks; rivers are polluted. The environmental consequences will be huge in the future. It is frightening.

In the short term one wonders how all these young people will find jobs. In the 90’s I did a horrifying story in Luanda about a few thousand street kids there. How they were attacked with pieces of glass by passersby they had robbed. These kids did not stand a snowball’s chance in hell. I read UN reports at that time warning that this number of kids without prospects would increase tremendously.

Well, it did. In all African cities there are now thousands and thousands of these street kids.

This type of hopeless poverty will keep on increasing, in the streets and the slums. And I don’t think NGO’s, the good-doers of this world, can solve that problem. The slums will be there for a long time to come.

Nairobi is divided 70 percent in a kind of slum areas (or disadvantaged areas, as the World bank cynically calls them), and the rest in the more affluent parts. Each area has its own economy, its own set of rules and culture and the poor have their own language. You have to be strong not to go into crime and lead a very short life in ‘these disadvantaged areas’. There is no confidence in politics and the rule of law.

Again: that feels frightening.

In Kenya, half a million private security guards protect the rich from the poor every day. That means that one percent of the population is employed to protect the assets and wealth of other one percent from the other 98 percent.

Politics

Politicians aloof from population

Progress in the economy does not have an equal match in politics. Most politicians live in such a different world from that of the common man. Kids of the elite only go to the countryside on school excursions, they would never dare to go to the slums, they hide behind high walls for protection. Just as the colonists had kept a big distance from their subjects.

The big issue of course is bad governance. In Kenya one third of the budget, it is estimated, disappears because of corruption. Not only do governments official steal, they behave with disdain towards civilians. The police uses us as ATM’s, other civil servants abuse us with other demands, there is no service mentality at all, no humility. And services by state institutions are under pressure. Courts have a huge back-log of cases, electricity disappears countrywide because monkeys or giraffes break wires, tapped water even in capitals is in short supply or is contaminated.

Today

Shuga. Men losing their balls. Solid Gold. Gen Z. Communalism to individualism

Each garden cites has become a metropolis. Old fashioned long English dresses for women and shapeless trousers for men, Homburg hats for men, short afro hair for teenagers have gone. The different genders walk hand in hand, rasta has become accepted, the rap, the hip-hop, the youth culture dominates the city streets and the villages.

‘A revolution is taking place. People who remember Kenya before 1990 will no longer recognise it.’ That’s what a young Kenyan actress and singer, told me in 2012. She was one of the actors in the soap opera Shuga, in which she was called Miss B’Have.

Shuga focused on the lives, love and complicated sex of young Kenyans. At university, in ghettos and in the lusty nightlife, the characters fought to realise their dreams. They did so in a rapidly changing world in which parents no longer had the final say, AIDS and homosexuals undermined old habits and the internet offered an escape route.

Miss B’Have told me:” Women have achieved such emancipation that we no longer wait for men to approach us; we actively pursue relationships ourselves. Two decades ago, couples would hesitate to walk down the street arm in arm. Today, some even have the audacity to kiss in public. Is this not a sign of progress?”

A year or so ago I read a little piece in the newspaper. A Kenya Demographic Health Survey showed that the number of mother-only households had risen to 31 percent in urban areas, and to 36 percent in rural areas.

Many Kenyans are still shocked by such changes; they grew up in a context of ubuntu, with the community being paramount, with men taking the lead. Now, many Kenyan men feel emasculated. They struggle with the disappearance of their traditional leading role in society. Globalization, individualization and Western traditions challenge African manners more and more. And Kenyan men are losing their balls in the process.

Also the role of young people changed, these educated people now compete with the traditional knowledge of the elders. Gen Z is easier in social conventions: it has respect but no longer fear of the old guard. Parents are respected but you no longer hide under your bed when the head teacher visits your parental home.

The once strictly separated age groups are crumbling and with them the authority of the elders. In the past, when they beat the holy drums, everyone fell under their magical spell. Now everyone has their own individual dream to fulfill.

With communalism on the retreat and with the new prosperity for some, it seems we are heading for a full-blown consumer society. Thirty years ago I saw for first time a padlock in the traditional life of the Samburu. Up till then apart from cattle things were owned communally, now people have taken the habit of hiding their beads, their packet of Omo, their shuka in a locked box.

In my personal experience it is that idea of consumerism, creating the desire among poor people to have a phone, a Nike, that’s what changes the behavior of people faster than anything else. Screaming billboards these days push the consumer into the wonderful world of consumer pleasure, on the way to a carefree future. Dare to live, be yourself.

Outside world, self-confidence of African leaders, but with their heads in the clouds

Africa’s place in the world is now not only connected to the West anymore. China saw Africa as an economic opportunity because of the new demographics. And so do the new so called middle powers like Turkey, the UAE, Brazil and Iran.

Ellis wrote: Decades of civilizing mission like development projects have left many Africans with something like an inferiority complex.

Leadership feels much more self-assured now. The continent has established a respected position within the global community, not as a beggar but as a preferred spouse. Leaders have become more assertive.

When a Dutch minister, or any other western minister, would visit, the rulers were trembling out of fear, because maybe he came to announce a cut in the so-called development aid. The western demands evolved around human rights issues but in reality, it was an effort to enforce liberal macro-economic changes. The West still thought that transfer of technological knowledge would end underdevelopment. That was a paternalistic attitude, undermining the self-confidence of African leaders.

The dependency syndrome is disappearing but now African leaders walk with their heads in the cloud, too self-assured. Because economic growth has slowed, China is more cautious with money, debt servicing is now 40 % of GDP, lockdowns during covid have harmed many and we are still recovering. We are going thru a delicate phase with possible a lot of social upheaval, like at the end of the 80’s en in the 90’s .

Youth Controversial elections. Backsliding democracy. Now wars within state structures (Ethiopia, Sudan)

With 60 % below 25 years, with little absorption of educated youth in the formal economy, we still live on a timebomb. Generation Z has shown us how that anger can be mobilised against regimes. But like with the multiparty movement, the youth are naïve to think they can overthrow an entrenched, a patronage-based, power hungry political elite. Rulers are fighting back, with detentions, with murders and the army and police shooting at demonstrators.

This Gen Z youth works within the democratic system and aims to gain power through elections. In the last 20 years, Africa has seen more than 410 elections. Most of these have been contested, and many resulted in conflicts. Only about 15 % of Africa’s elections of the past two decades have ended happily.

This development raises the spectre of democratic backsliding. Frequently, civilian governance results in bad governance, making military rule a readily alternative. The increase in military coups, particularly in the Sahel region, along with the manipulation of constitutional frameworks, reflect a democratic defect that seems to be exploited in some political systems.

We live in a post-colonial society, in many parts of the world and in also Africa. With many structures from the past still existing, like government appointed chiefs to spy on the population, with a mix of fear and respect for the Big Man, with policemen who harass us. And with a big disregard for human life.

The arrogance of power is disgusting, really. Imagine this: 129 inmates killed by warning shots after they tried to escape from the notorious bad Makala prison in Kinshasa. Just killed them! Nigeria detains some kids with treason charges because they were picked up during Gen Z demos and initially faced the death sentence. Are we killing our youth?

The wars of the 80’s and 90’s were wars against the central state. Now we see wars within the central power. See Sudan, Ethiopia etc. Wars that are very destructive, wars that don’t bring hope but despair. The war in Tigray has been one of the most criminal wars ever noticed in Africa with an unimaginable number of casualties, hundreds of thousands died.

Sudan is in disarray. The destruction of infrastructure goes along with the erosion of the unique social fabric and hospitality that characterize Sudanese society. For decades, animosity will take root, war trauma’s will be festering for a long time, the ones who died maybe have been the lucky ones.

My experiences with conflict have taught me that when the madness really is set loose, people feel no restraint at all to dismantle the state infrastructure anymore, they lose the sense of belonging to one’s country. The collective identity is being pushed aside, by hatred and by cynicism.

Meanwhile, the international community appears to be merely observing, waiting for the situation to resolve itself. This absence of empathy is unprecedented. A shift seems to have occurred in global relations; it appears that the world is unable to manage more than two major conflicts at a time.

But far away from the central power there is a new Africa emerging. One that thrives of the freedom to do business, one that is being run by young, well-educated middle-class people, a new Africa that has completely embraced internet for communication. With internet these young people wrestle their freedom from the old guard, the freedom that they have missed out on for so many decades. There will be more Seasons of Rains coming, and once more we are looking for the inspiring, that stimulant smell of that coming rainy season that will emerge from this new group of people.