Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

Part one of the story Samburu the way it was: The way it was in Samburu: Unity of five fingers on one hand, in a pastoral world

There will be houses here with corrugated iron roofs. There will be a school and we will no longer have bows and arrows but guns.

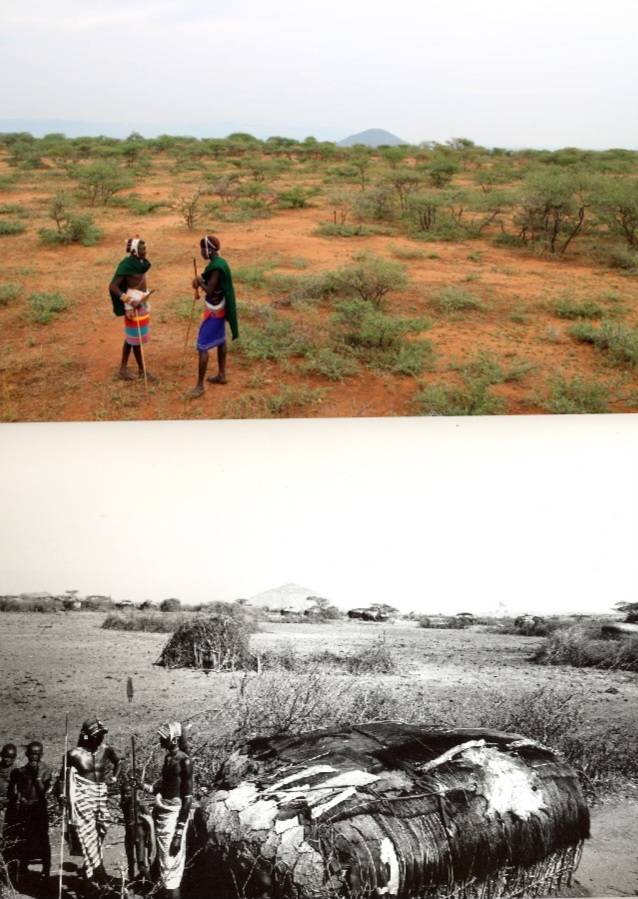

The village of the Samburu people had not yet come into existence when a laibon, or diviner, made this prediction around the year 1989. He gazed over a collection of low houses made of branches and cow dung, the ceremonial boma (kraal) for warriors, with Mount Lowuamar (‘the big neck’) in the distance. The makeshift settlement was demolished a year after, only the ash-saturated bare spots where the women cooked tea reminds us of that day 35 years ago. Apart from that, nothing in the area has remained the same.

Resim, the name referred to both the village and the surrounding region was an inward-looking world, hidden in the arid and thorn-laden tree savannah of Northern Kenya. There was no road, no stone building, no electricity, and no running water. “We felt at ease in our own world,” recalls Lonis Lemelen. He is around 65 years old. “As warriors, we spent our time achieving ultimate beauty, by painting our bodies and with our bead necklaces.”

With his walking stick, he directs a group of young warriors to the location where his mother’s house once stood. “My age group was born when our parents were still traveling. Until we got fewer cows, we stopped and settled in Resim. Grass was still growing everywhere, there was space and many wild animals lived there. There was enough rain, the world was not yet destroyed.”

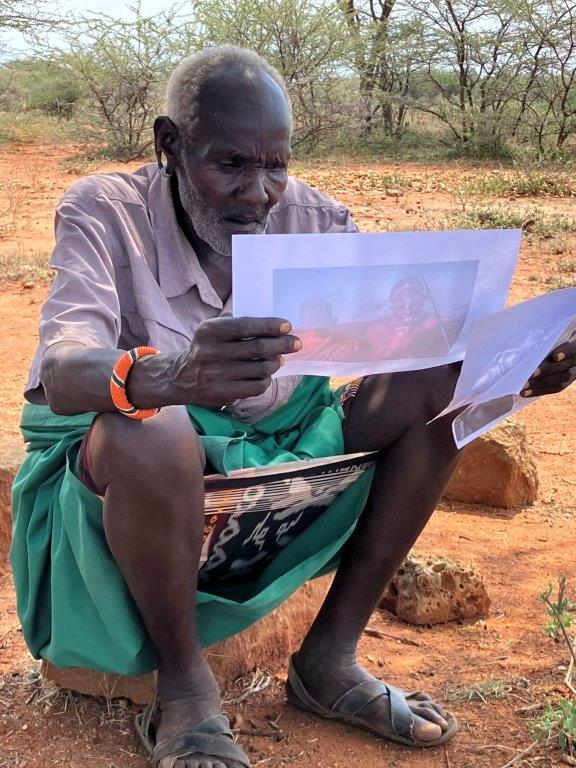

Looking at photos from back then causes Lemelen pain. Too many of his peers are dead, from disease or killed in cattle raids. “We were strong warriors,” he sighs. Today’s warriors look along and let out sounds of surprise. “You walked around half naked,” they giggle about their parents’ visible thighs. “We tie our loincloths tightly around our waists.”

Lonis Lemelen gestures for them to be silent. “Listen,” he says, “we told our parents about school, but they did not want to know anything about it. The old men who gave birth to us made a big mistake. My agemates however understood that you can communicate with letters on paper.”

Solar panels

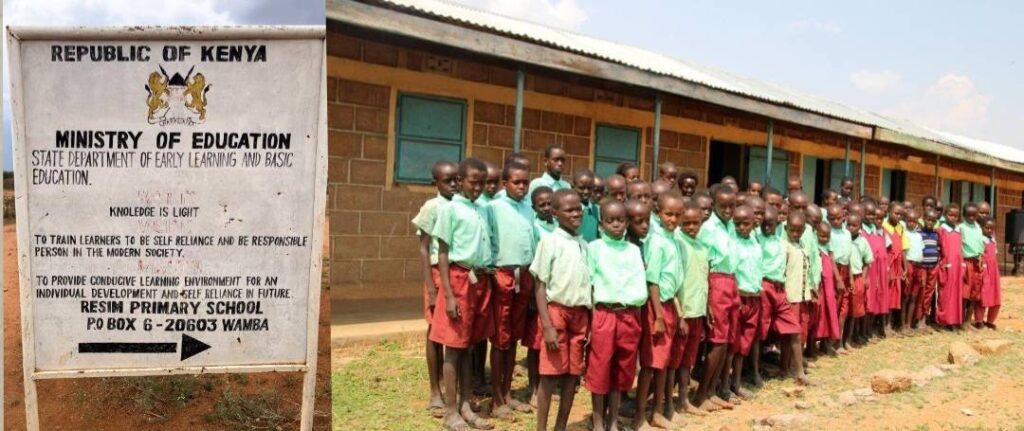

The coming of the school, that made everything different. A few years after the predictions of the diviner, on their own initiative, the elders of Lonis’ age group built a nursery school, a kilometer away from the ceremonial kraal. It was the first stone building of Resim, followed after the turn of the century by the first classrooms for a primary school. Each family contributed a goat as a financial contribution and thus the tide began to turn in the traditional life of the Samburu. In the past, children came to maturity through their parents, who taught them the culture of the Samburu and the knowledge of nature. Once the boys were initiated as warriors, they would wander the savannah with their peers. That freedom of the bush has made way for the rigor and discipline of the school benches.

The school now serves as the central hub of the village of Resim. Adjacent to it lies a football field, and a weekly market takes place nearby. Religious propagators have established two rudimentary churches, which are exclusively attended by women only, as the Samburu have their own spirituality. The government has designated a chief to maintain oversight and order, and it funds the salaries of four teachers. The roof is equipped with solar panels supplied by the government, which serve as the sole source of electricity.

The head teacher is Emmanuel Lenkokwai. On some days he is confronted with stubborn warriors who still refuse to attend school. “One teacher was scared to death when such a warrior entered his classroom with a spear and a club,” he says. “Those warriors are not dangerous, mind you, but they are arrogant. He just came to charge his phone. These warriors say that the school belongs to the community so they can enter freely and sleep there at night.”

Modern education is putting pressure on the traditional sense of community. “I teach my students to be individualistic and to be the outlier in the class. That encourages inequality,” explains teacher Peter Letipo. “The Samburu’s mutual ties have become much looser.” Lonis Lemelen agrees with Letipo. “In the past, you needed me and I needed you, but now that equality has eroded because money has made us less dependent on each other.”

Women

The girls benefited most from the change. “Previously, decisions were made by older men, but now it is the teachers who hold authority. At school, boys and girls are treated equally,” states 19-year-old Rose Ntoipana. She participated in all the classes offered at the school, thereby avoiding early marriage and the related circumcision. In former times, girls would confine themselves to their mothers’ homes during their menstrual periods; now, they receive sanitary towels at school.

“I hope to marry someone I love and who has been to school. I want to make my own choice. My girlfriends think the same way.”

Lonis Lemelen’s mother encouraged him to sleep with many different girls during his warriorship. In the evening, the high-pitched singing of girls, supported by the bass of the warriors, could be heard in all the homesteads. The perky breasts and flapping loincloths created an erotic atmosphere. “You don’t come to school with bare breasts,” laughs teacher Peter, “you learn to be ashamed of it.”

Market day

It is Wednesday, market day. An elderly woman buys a 5GB memory card and asks a young man with an old-fashioned gun to put it in her phone. “I will put some music on it for you via Bluetooth,” he promises. The residents of Resim sing less and listen to songs downloaded from the internet. Old men with homburg hats and young people in modern frayed trousers seek shade under a tree, from which hangs a recently slaughtered goat. Traders from outside spread their wares on the ground: sugar, tea leaves, clothes, and some salt. A nurse opens his large chest of medicines; the owner of a car full of the drug miraa is the first to have sold all his wares.

In an igloo made of branches covered with black plastic, Lemelen’s two wives cook a mouthful of rice and beans. In addition to this restaurant, he owns one of Resim’s three permanent shops. That is where Resim’s first crime took place last year. One night, a crate of beer and packets of biscuits disappeared. “I followed their trail, I could see who they were by their footprints. However, the elders decided not to make a big deal out of it, to prevent discord in the community.”

Green world of happiness

As the sun sets, the merchants depart from Resim along a newly built rural road. Lemelen traverses a rocky path towards his kraal, his walking stick balanced on his shoulders. The dwellings within the kraals of Resim continue to be constructed from cow dung, furnished with beds made of hides and straw. The residents attend to their sanitation needs in the open fields. Gradually, the first goats return, while mothers call out for their young ones to come and feed.

Lonis Lemelen’s second wife drags a sheep by its hind leg away from her bleating child and starts milking her. A camel lets out a long groan and a goat escapes from children playing tag by jumping on a house. It is a green world of happiness; the rain has fallen abundantly in recent months. Until the soft sea of nature sounds is torn apart by a warrior riding into the kraal on a moped.

In the sweet smell of cow dung, the old men sit on their milking stools and send phlegms of saliva to the ground. The youngsters each press a stone under their bottoms. At their feet, the cows chew the cud. In the houses, women make cups of milk tea. “We used to sit and talk like this for hours,” says Lonis Lemelen. “We discussed family quarrels, the weather, the grass, until we reached a consensus.” Meetings are short these days, often a quick get-together on the sidelines of the market, or in a telephone conversation. “We had all the time, but now we live with routines and schedules.”

Resim has shaken off his isolation, the proponents of founding a school 35 years ago praise the progress. Their biggest concern: climate change and the shrinking of living space. “I hope that our educated children can do something about that,” says Lonis Lemelen. He has two wives and thirteen children, his brother three wives and fifteen children. “Back then we were only a few, then we counted ourselves rich with many children. Now you are poor with plenty of children, because all your money goes to school fees.”

The other big challenge lies in maintaining the unity of the Samburu community amidst a schismatic modern age. A young family member of Lemelen enters the kraal, with schoolbooks in his backpack. The warriors separate themselves into the uneducated and the educated ones. The educated youngsters complain about how difficult the subjects of agriculture and mathematics are, the warriors of the bush decide how to deal with a leopard which stole a goat last night. “We have more important things to discuss,” the educated laugh scornfully.

This article was previously published in NRC on 21-8-2024.

Copyright all photos Koert Lindijer