Over time, Eritrea’s paranoid nationalism has hardened into a permanent state ideology. It functions to normalise repression, justify isolationism, and foreclose the possibility of political pluralism. This nationalism endures by convincing Eritreans that the gravest danger is always imminent – and that only total loyalty to the regime can avert catastrophe.

By Dawit Mesfin

In the years following Eritrea’s independence, I began to experience a quiet unease that I could not immediately name. It did not manifest as anger or overt disappointment, but rather as a subtle tension beneath the prevailing sense of pride – something felt more than articulated. What was celebrated as unity forged through sacrifice gradually revealed a more rigid and exclusionary character.

Over time, I came to recognise a closed, self-reinforcing system in which apprehension, paranoia, and extreme nationalism sustained one another. This system was upheld not only through coercive practices, but also through a powerful narrative: that the nation remained unfinished, perpetually in recovery, and under constant threat, and was therefore not yet accountable – to its citizens or to itself.

Some of my clearest memories from this period involve conversations with former freedom fighters – friends and family whose courage I deeply honour – in which I found myself carefully weighing each word. I raised questions tentatively, almost apologetically: about democracy, accountability, and the forms of governance a liberated country might now pursue. Even these measured inquiries felt like transgressions, as though an invisible boundary had been crossed. There was an unspoken consensus that such questions were premature, or simply out of place in the present moment.

I spoke of the future I had hoped for: sustained investment in civilian life; the strengthening of schools and institutions of higher learning; the mobilization of knowledge and expertise within the diaspora; and the return of those willing to contribute to national reconstruction. I argued for easing bureaucratic constraints, restoring confiscated businesses and properties, and allowing civil society and private enterprise to function with greater autonomy. The response was invariably the same: time was needed; resources were insufficient; alignment with the prevailing order was essential. These replies were delivered calmly, even benevolently, yet their uniformity was deeply unsettling. The conclusions appeared to precede the discussions, as though the outcome had already been determined.

As the years passed, this refrain grew more rigid and less tolerant of dissent. What had initially been presented as prudence hardened into certainty; what had been justified as temporary delay evolved into outright refusal. Debate itself came to be regarded not as difficult or ill-timed, but as unnecessary. At that point, it became clear to me that the liberation struggle had not merely postponed freedom – it had subtly redefined its meaning.

During this period, I read Haddas Eritra, the government newspaper, with close attention – not as an act of endorsement, but as a means of understanding how the state sought to represent itself. In retrospect, the paper’s consistent emphasis on the victorious EPLF was striking, particularly when contrasted with its marginalisation – if not erasure – of civilian contributions, as though the population existed only as a backdrop to the struggle.

Progress or “Progress”

Its pages were saturated with declarations of progress. Lists of thousands of citizens purportedly granted import–export business licences were published, accompanied by stories of civilians benefiting from thriving enterprises – accounts that functioned less as reportage than as a mechanism of persuasion, designed to entice unsuspecting citizens into “investing,” effectively surrendering their capital.

The newspaper also announced the construction of schools and clinics across the country, dams under development, roads being paved, and ambitious plans for nearly every sector of the economy. Employment appeared plentiful; prosperity, perpetually imminent.

On paper, the nation seemed to be moving forward with confidence and remarkable speed. Yet the language felt inflated, the optimism rehearsed, and the gap between what was described and what was quietly lived continued to widen. The narrative seemed less concerned with reporting reality than with shaping perception – especially for the diaspora, the international community, and prospective investors – while the new rulers, the EPLF, settled into power.

Time, more than any argument, revealed the truth. Years passed, and then decades and the promised transformation never arrived. Instead, poverty hardened into permanence, corruption seeped into the texture of daily life, and those who sought to invest found themselves trapped in a labyrinth of delays, contradictions, and unresolved permissions.

Those who moved too quickly to build – transferring their capital to Asmara in good faith, before any clear precedents existed – were left exposed. Their resources lay immobilised, their plans suspended indefinitely, their ambitions slowly and silently abandoned.

In retrospect, the period feels almost surreal: a diaspora repeatedly summoned to hope, to wait, to believe that change was just over the horizon. The regime spoke in the language of composure and ceremony yet governed without coherence or restraint.

Gradually, an unsettling clarity emerged – this was not a temporary departure from principle, but a settled mode of rule. The men who had assumed power at independence remained in place, aging in office, while the nation itself seemed to grow old with them, caught in a prolonged and weary stillness.

The consequences of this prolonged dissonance are now difficult to ignore. The long-anticipated return of Eritreans from the West never came to pass. Instead, tens of thousands chose departure over endurance, escaping through dangerous and uncertain routes.

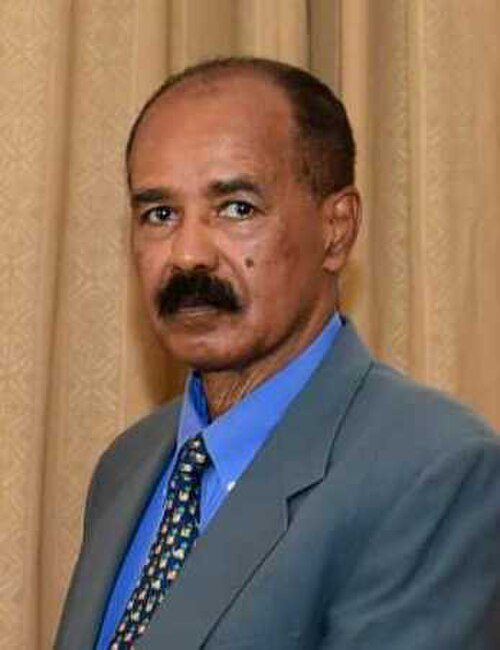

As Isaias Afwerki consolidated his hold on power, corruption ceased to be an aberration and became a condition of governance. With institutions of accountability – the judiciary, law enforcement, and the press – reduced to instruments of control, corruption no longer required concealment. It settled into the routines of public administration, unremarked and unchallenged. What emerged was not merely a failure of leadership but the slow formation of a kleptocratic state, where public wealth dissolved without explanation and the idea of consequence itself gradually lost meaning.

Nothing materialises

It was in those moments that I began to see how nationalism, once a language of liberation, had been repurposed into a language of authority. The struggle was endlessly rehearsed as moral capital, the future perpetually deferred, and dissent reframed as betrayal. What called itself vigilance was often fear; what passed for unity was enforced silence. The myth did not merely explain the present – it froze it, sealing the country within a single, unchallengeable narrative.

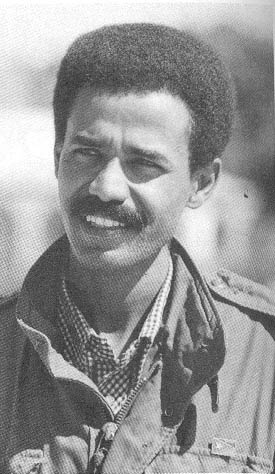

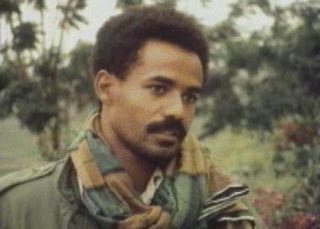

Years later, I found myself listening more closely to lengthy interviews with President Isaias Afwerki on matters of development – topics uncannily similar to the questions I had once raised, as a novice, in private conversations. He spoke at length about macroeconomic policy, self-reliance, housing schemes, urban planning, infrastructure, and poverty reduction. Everything, it seemed, was articulated with unwavering certainty, year after year, since 1991 – as though the vision existed fully formed in his mind alone.

And yet, nothing materialized.

The words accumulated; reality remained unchanged. What endured was not development, but the performance of intention – an endless monologue standing in for action.

I once heard him make a brazen – almost surreal – claim while describing Eritrea as it supposedly existed before his rule. He evoked a nation in full bloom: hundreds of factories and small enterprises, export-quality production, and a public administration that was efficient and responsive. It soon became clear, however, that he was recalling Eritrea of the Italian era. With unwavering confidence, he recited a catalogue of flourishing industries, solid infrastructure, and general prosperity, until the account slipped from selective memory into outright fantasy. I listened in open disbelief.

Grip on power

Since 1991, he and a narrow circle of former freedom fighters have effectively appropriated Eritrea in its entirety. Reformist comrades were side-lined or eliminated, dissent was criminalised, and power was steadily concentrated in his hands alone. Under this rule, the country bled its inherited wealth – assets accumulated during the colonial period, the British Military Administration, the Haile Selassie years, and even those that, despite systematic neglect, endured the Derg military junta. One by one, these were squandered or destroyed.

Asmara and other cities were drained of their vitality; water and electricity systems deteriorated into chronic dysfunction. Confiscated factories and businesses were left to decay – not through war or sabotage, but through deliberate neglect. Yet he remained firmly entrenched, evading accountability, deflecting blame, and presiding over a nation that slowly unravelled around him.

His manner leaves little doubt that he regards the citizenry as wilfully ignorant. He harangues Eritreans ad nauseam, scolds the international community over its alleged sins, and indulges in self-appointed lectures on regional geopolitics – as though directing traffic in a catastrophe of his own making. Meanwhile, he incessantly warns of enemies lurking at every corner, conjured as needed to justify repression, stagnation, and perpetual mobilisation.

His interminable monologues expose a mind trapped in repetition and deflection. The script is always the same: condemn others for his failures, manufacture pretexts for national collapse, inflate imaginary threats, and deliver ponderous lectures on the Cold War – his favourite obsession – alongside his endlessly recycled readings of the region. These performances, among the dullest and most predictable in contemporary African politics, crowd out any serious discussion of Eritrea’s reality: the deliberate suffocation of domestic political life and the systematic dismantling of a nation under the guise of liberation.

Isaias Afwerki presents himself as indispensable to the nation’s survival – cast as the final bulwark against an impending catastrophe that exists largely within his own political imagination. His nationalism is not simply authoritarian; it is structurally paranoid. It thrives on a condition of permanent alarm, requiring a continuous production of enemies in order to sustain its legitimacy. Absent an ever-present threat, this form of nationalism would collapse under the weight of its ideological emptiness.

Fear is systematically weaponised to cultivate a bunker mentality, one in which loyalty to the state supersedes truth, pluralism, and individual rights. Conflict need not be real or imminent; the mere suggestion of external or internal attack is sufficient. A suspended state of emergency thus becomes the governing norm. Extraordinary controls are imposed “until the danger passes,” yet the danger is perpetually deferred, for a nation at peace would no longer require a self-appointed saviour.

Within this paranoid nationalist logic, patriotism is equated with unconditional trust in the leadership. To question authority is to signal disloyalty; dissent is recast as collaboration with the enemy. Political opposition is thereby stripped of legitimacy and transformed into a security threat.

Over time, Eritrea’s paranoid nationalism has hardened into a permanent state ideology. It functions to normalise repression, justify isolationism, and foreclose the possibility of political pluralism. This nationalism endures by convincing Eritreans that the gravest danger is always imminent – and that only total loyalty to the regime can avert catastrophe.