On the morning of election day, the streets of Dar es Salaam, the economic capital, were mostly empty. Then the violence broke. “It was clear the movement was spontaneous, and lacked coordination.”

“I saw several people shot – some collapsed instantly, others were carried away bleeding”.

“Security forces have been storming homes, dragging citizens out, and shooting them on their doorsteps for daring to protest”.

Numerous reports suggest that plainclothed Ugandan security forces took part in some of the civilian shootings, deployed as part of an unofficial pact between Tanzania’s president Hassan and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni.

Some witnessess speak in this article

By Guillaume Antignac

A young man stumbles along a street with a bullet hole in his cheek, as blood spills from his mouth and nose. In another, a man is lying against a wall, holding his bloodstained t-shirt against a bullet wound to his abdomen. Yet another shows at least a dozen corpses piled together outside a clinic.

These are just some of the countless videos circulating online that depict the security forces’ brutal response to public protests over Tanzania’s 29 October elections in which hundreds, possibly thousands, of demonstrators were shot dead.

UN human rights chief Volker Türk on 11 November called for an investigation into the killings, and into further allegations that the police had moved bodies from the streets “to undisclosed locations” to conceal evidence.

Tanzania’s main opposition party, Chadema, has also called for an inquiry by the United Nations, the International Criminal Court (ICC), and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) – among other international bodies.

Describing the killings as “the worst human rights crisis in Tanzania’s history”, Jumuiya ni Yetu (the community is ours) – a coalition of African civil society organisations – is independently collecting evidence for a submission to the ICC.

Mwanase Ahmed, a human rights defender with Jumuiya ni Yetu, said although the “government’s censorship and cover-up” made counting the dead difficult, the names the group has so far compiled – and lists they’ve seen of people searching for their relatives in hospitals and police stations – suggests that between 5,000 and 10,000 people were killed by the security forces.

“Those that planned, financed, and carried out the massacres must first be brought to justice. Samia must also unconditionally step down – we do not recognise her as democratically elected.”

The diplomatic fallout of the election violence has been significant. Poll observers from the African Union and SADC failed to endorse the ballot, and an official tally that gave President Samia Suluhu Hassan close to 98% of the vote. Regional leaders will be under pressure to act on the findings of their observer missions.

So far, their preferred option seems to be some form of transitional political arrangement. Tanzania’s Vice President Emmanuel Nchimbi said on 9 November the government favoured dialogue, but gave no further details. A day later, senior Chadema figures were released from detention.

Amid fears the government may be trying to divide the opposition – who had effectively been banned from the election – two Chadema party leaders told The New Humanitarian there can be no reconciliation before accountability in a country still traumatised by the violence.

“Those that planned, financed, and carried out the massacres must first be brought to justice,” said John Kitoka, Chadema’s director of foreign affairs. “Samia must also unconditionally step down – we do not recognise her as democratically elected.”

Chadema is also planning to take to the streets on 9 December – independence day for mainland Tanganyika – in what they hope will be an emphatic repudiation of Hassan and her ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party.

“We know Samia is power-hungry and they will use live bullets,” said Liberatus Mwang’ombe, a Chadema coordinator. “But we want our voices to be heard.”

The crackdown and its aftermath

On the morning of election day, the streets of Dar es Salaam, the economic capital, were mostly empty. As the afternoon wore on, groups of protesters began to gather around the neighbourhoods of Ubungo – the location of the country’s largest bus terminal – and the usually busy marketplace of Kariakoo.

Word spread quickly online and, within hours, crowds were pouring into the streets across the country.

“At first, it seemed almost like a joke,” said a reporter who witnessed the protests forming in Ubungo. “It was clear the movement was spontaneous, and lacked coordination.” The reporter, like other unnamed sources in this report, asked not to be named for fear of reprisals.

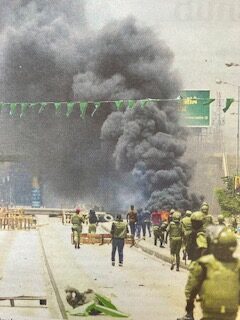

Things quickly degenerated. Polling stations, police stations, and businesses associated with wealthy CCM backers were set ablaze during the night. In the next few days, there was widespread upheaval as protestors – a broad demographic spectrum of Tanzanians – rallied against the government.

A curfew was quickly enforced, roadblocks set up across city centres, and the internet was shut off.

In multiple videos circulating online, in addition to uniformed security personnel shooting at protesters, men in civilian clothes could be seen patrolling the streets with assault rifles firing indiscriminately. “I saw several people shot – some collapsed instantly, others were carried away bleeding,” said one witness.

“Security forces have been storming homes, dragging citizens out, and shooting them on their doorsteps for daring to protest,” Jumuiya ni Yetu said in a statement.

Mwang’ombe of Chadema said he had spoken to doctors who said they were told by police at gunpoint not to reveal the numbers of the dead and wounded arriving at their hospitals. “The government is working extra hard to conceal the dead bodies,” he added.

Jumuiya ni Yetu is assembling a list of alleged perpetrators for submission to the ICC. Among those named are Hassan and her son, Abdul Hafidh Ameir, who is believed to have led a pre-election undercover abduction and assassination squad.

A flawed election

In the months leading up to the election, abductions had been rising sharply as the government cracked down on Chadema and its leader, Tundu Lissu. He was arrested in April on treason charges for calling for a boycott of the elections after Hassan failed to follow through on promises to reform the electoral system.

The electoral commission disqualified Lissu, followed by Luhaga Mpina, the candidate of the second largest opposition party, ACT-Wazalendo. That left Hassan facing only minor opponents at the polls, as rights groups condemned the climate of fear.

On election day, a preliminary SADC statement noted a “very low voter turnout”, with some polling centres receiving “no voters at all”. Members of its observer mission witnessed ballot stuffing, but the team was unable to verify the vote counts due to the internet outage at the end of the day.

Although Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, the chair of the African Union, congratulated Hassan on her win, a statement from its electoral observer mission said the poll did not meet democratic principles or standards.

Samia’s system of rule

The frustrations that led Tanzanians onto the streets in protest can be traced back a decade or so. CCM was Tanzania’s founding independence party, and has stayed in power throughout the multiparty era that began in 1992.

But it has since split into two unofficial yet distinct factions: those who retain a conviction in the party’s core values, and those hungry for the benefits of rule.

When John Magufuli came to power in 2015, it was thanks to his reputation as a hard-working ally of the former faction. He was popular for his publicly tough attitude to corruption and his sovereigntist stance on foreign investment. Many saw him as the right man to tackle the deeply entrenched graft that had set in under his predecessor, Jakaya Kikwete.

“Magufuli came to power when corruption had reached unheard-of levels,” a Tanzanian cartoonist and award-winning anti-corruption activist told The New Humanitarian. “He showed results. Within a few months, public services had already improved.”

Magufuli’s strongman persona won him support among many Tanzanians, but it also came with a sharp rise in authoritarianism. Criticism was barely tolerated, and it was during his tenure that the crackdowns on opposition parties intensified – although they were not blocked from participating in elections.

“Under Samia, Magufuli’s good side has disappeared, while his bad side has only gotten worse.”

Hassan, then vice president, took over with Magufuli’s death in 2021 from heart-related complications. Many were hopeful she would continue his policies but without the authoritarian shortcomings. They were initially rewarded. Hassan released political prisoners, eased the pressure on the opposition, and was feted as a reformer.

But repression, disappearances, and killings soon followed. “Under Samia, Magufuli’s good side has disappeared, while his bad side has only gotten worse,” the anti-corruption activist said.

Allegations of graft also mounted. A 30-year concession for Emirati logistics company DP World to operate the port of Dar es Salaam infuriated Tanzanians after the government refused to make the contracts public.

Hassan’s connections to Magufuli’s predecessor, Kikwete, have also been seen as part of a broader graft network. He had been a mentor earlier in her career and was invited back into politics to reportedly serve as a confidant.

The clique around Hassan also includes Rostam Aziz, a longstanding MP and one of the richest men in East Africa. Kiwete and Aziz were linked to a $133 million scandal at the Bank of Tanzania involving foreign investors that was allegedly used to finance Kikwete’s presidential campaign in 2005.

In July 2025, whistleblower Humphrey Polepole, a longstanding CCM minister and the ambassador to Cuba, publicly resigned, denouncing the party’s serial abductions and disregard for human rights.

In a series of videos ironically titled Shule ya Uongozi (leadership school), he alleged that a group of wealthy Tanzanians had taken advantage of Magufuli’s authoritarian system to seize control of the government under Hassan.

East Africa’s authoritarian states

Tanzanians point to a regional dimension to the violence. Numerous reports suggest that plainclothed Ugandan security forces took part in some of the civilian shootings, deployed as part of an unofficial pact between Hassan and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni.

“Some of these mercenaries were pinned down by protesters. And when they were pinned down, they could not speak Swahili,” said Mwang’ombe. “In Tanzania, there is no military person or police officer who does not speak Swahili.”

The authoritarian governments in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania have “colluded” to crack down on dissent, said Kivutha Kibwana, a former Kenyan MP. “These dictators are working together. The responses to these protests are very similar – it’s like there’s a rulebook,” he told The New Humanitarian.

A series of abductions of political activists from Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda – and their renditions – have taken place in recent years. “Those are the things that tell us there is this collaboration,” said Kibwana.

Agather Atuhaire, a Ugandan pro-democracy activist, was one recent high-profile case. She was abducted and allegedly sexually assaulted by the Tanzanian police in May when she attended the trial of Lissu, the Chadema leader. She was then dumped at the border, along with Kenyan political campaigner Boniface Mwangi.

“The three countries are engaging in cross-border abductions, illegal renditions, and torture,” Atuhaire told The New Humanitarian. “I was a victim of that.”

But there has also been a deepening of civil society solidarity. “I think East African citizens are fed up with repression, kleptocracy, and impoverishment,” Atuhaire noted. “Most of its citizens are young people who have grown up in the era of social media and have access to information. So they’re mobilising one another easily.”

Yet civil society anger may not be a match for loyal security forces and state institutions – as has so far been the case in Tanzania. The AU and SADC are also unlikely champions of grassroots political reform.

“A concern is the tendency of heads of state to allow this to blow over, and then go back to business as usual,” said Chidi Odinkalu, a professor in International Human Rights Law at Tufts University’s Fletcher School. “There needs to be an escalation of regional and related diplomatic pressure in response.”

Yet Chidema’s Kitoka struck an upbeat note. “We don’t place our hopes in anyone other than Tanzanians,” he noted. “As Tanzanians, we are going to reclaim our country. Whoever wants to support us needs to know that.”

This story was first published by the Humanitarian.