Koert Lindijer has been a correspondent in Africa for the Dutch newspaper NRC since 1983. He is the author of four books on African affairs.

The time has come for Johannes Pieter Pronk’s memoirs. After surviving a major heart attack last year, the former Dutch development minister, born in 1940, feels as if every new day is a bonus for him. At his home in The Hague he whips through reports of his many diplomatic encounters and does that with with the same strict discipline as he showed as minister. Some of these meetings took place in presidential palaces but many were with guerrilla fighters along the Nile or desperate Rwandans deep in the Congolese jungle. His first volume is called “Battle of the Great Lakes”, and it focusses on the crises in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo during the nineties.

Pronk was always helpful towards journalists during his working visits. I often travelled with him, but one never really got to know him. Pronk always came across as an intellectual, not an emotional person. The latter only very occasionally, very briefly. We were once flying to Northern Kenya when suddenly the windows were covered with thick black slurry. The pilot warned us he might have to crash-land. After a successful emergency landing, unloading ourselves while peeing side by side on the runway, I heard some emotion in Pronk’s voice. “Life is certainly worth living,” he sighed. But a few minutes later, when the pilot had screwed the cap on the oil tank, he sounded distant again: “Luckily I’m am still in time for the parliamentary debate tomorrow.”

Read further:

-How Kofi Annan let Pronk down

-How Pronk in vain asked Kagame not to hurt a dissident minister

-How Meles Zenawi wanted to do his masters with Pronk on the subject of human rights

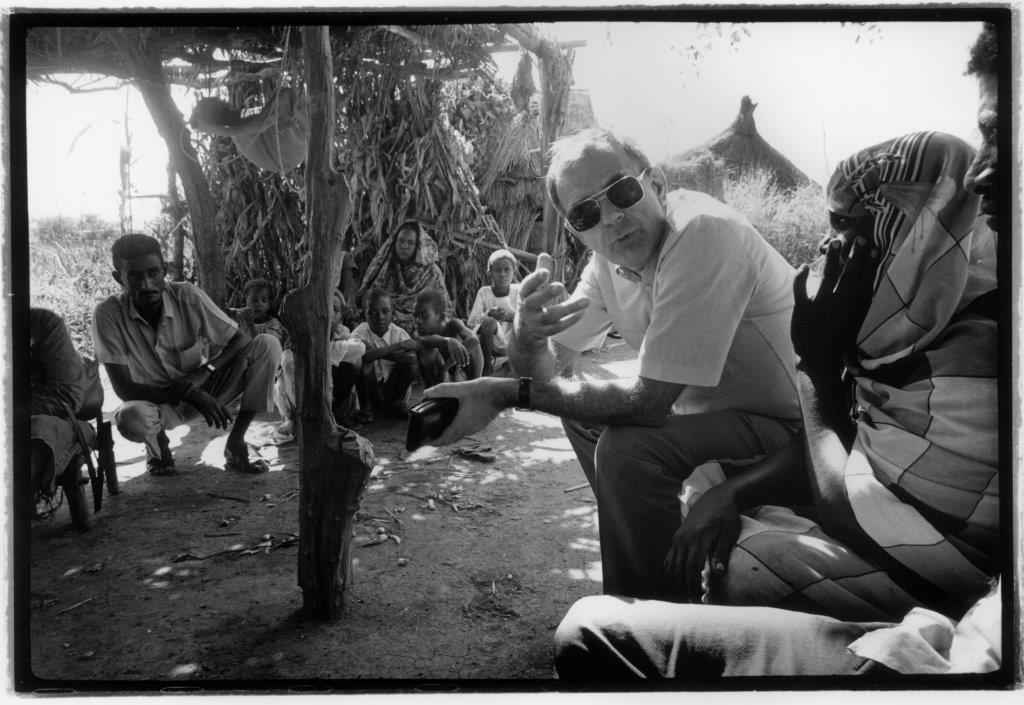

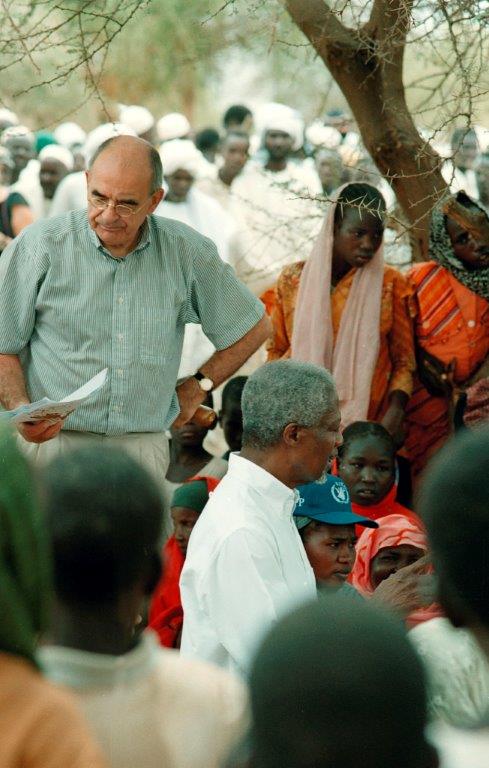

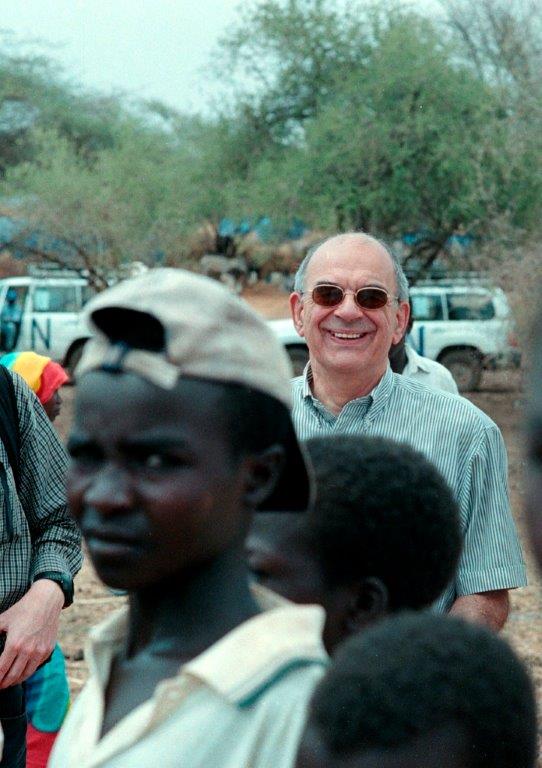

All pictures of Jan Pronk and Kofi Annan by Petterik Wiggers

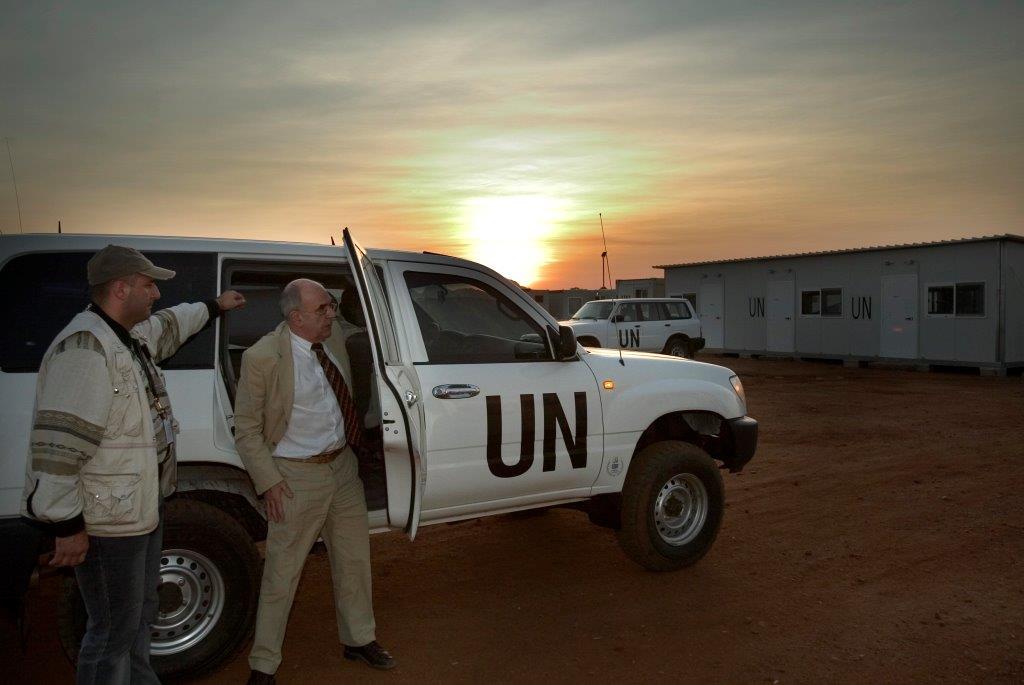

After serving as development minister, Pronk was in 2004 appointed UN Special Representative in Sudan, when President Omar al-Bashir, with the help of the Janjaweed militia, suppressed a rebellion in Darfur, a war America labelled genocide.

Relations between the West and the Sudanese regime are very different now. “It is a disgrace,” he says. “We now support Bashir. We now, with European help, assist the Janjaweed, who they call border guards, stopping refugees from Sudan and Eritrea. It is not a genocide but there is a manslaughter taking place with Western involvement. I don’t call this cynicism, no, it is much worse. Politics are now purely focused on ourselves. Politics are strategically inward-looking these days.

“America first, Europe first, Netherlands first, you name it. The way they have dealt with Greece. That was not an act of cynicism by (the Dutch Minister of Finance) Dijsselbloem, it was calculated Northwest European self-interest. The Greek population was the victim, and then he blamed them, the victims always get the blame. Greek’s debt was a consequence of the international financial system, which encouraged certain countries to reduce budget deficits, because otherwise you would have to pay huge interest rates on loans that you might not get anywhere. That is not cynicism, I wish it was. Cynicism is when you think it won’t work out anyway, no, this is calculated self-interest “.

Blinkers

-Weren’t you just very naïve at the time?

“No. I never had blinkers on. Anyone who closes their eyes to the functioning of the global capitalist system is naïve. Just like those who think we can stop refugees. And those who think it is only about ourselves. Those who want to protect their own white Dutch identity – because that is what it is nowadays in the Netherlands”.

As a minister, Pronk had to deal with a poor and needy African continent. Those times are over. But he warns that things are not going well with Africa.

“Macro-economic growth means many are doing well in Africa. But that does not apply to everyone. This development process led by the West mainly impacts the elite and upper middle class. Because they operate in the same market that we do. So, we focus our support, our trade and development aid on those groups, not on the ones at the bottom. They are pushed further down and that leads to escalating conflict and repression “.

Pronk’s life has been full of both great ideals and their betrayal. Pronk cites Prime Minister Joop Den Uyl and the economist Jan Tinbergen as his inspirations. Den Uyl embodied the sky is the limit ambitions of the sixties, Tinbergen launched theories on the global redistribution of labour and wealth.

The world would be improved through idealism and the realisation of a just socio-economic model, Pronk believed. He wanted to be a partner in resolving conflicts in Central and East Africa and sat around the table with the young leaders who won power there in the eighties and nineties, albeit often at the barrel of the gun: Yoweri Museveni in Uganda, Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia and Paul Kagame in Rwanda. Dutch money was spent supporting them. The somewhat formal but always passionate minister gained more respect and influence in Africa than his Dutch predecessors or successors ever did. But he was cheated by Kagame, quickly lost confidence in the headstrong Museveni and the Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi bitterly disappointed him.

Rwanda

Rwanda’s 1994 genocide was the most dramatic event of his career and the focus of the first volume of his memoirs. Over a million of people were slaughtered, first in Rwanda itself and then in a war in neighbouring Congo. He was one of the very first European ministers to rush to Rwanda and established a close relationship with Paul Kagame, leader of the insurgents and now president of the country.

In retrospect, that relationship seems controversial, especially in the light of new publications which examine Kagame’s allegedly murderous behaviour. A few times, Pronk writes in his book, Kagame betrayed his trust. He cheated him by denying in 1996 that his soldiers had invaded Congo and were involved in fierce fighting there. Although journalists actually saw Rwandan soldiers in Eastern Congo, Pronk insisted on believing Kagame. And despite those lies, he continued to work with him.

“What else can you do? Turn away from him? The worst thing was when I asked him straight out: is your army in Congo? He said “No”. The only alternative is that you feel so insulted that you retreat. So, you continue to work together, to exert pressure and to maintain as much of the human rights agenda as possible. But yes, you are dealing with power-hungry players “.

After nearly a million deaths during the genocide in Rwanda, hundreds of thousands more died in Congo. And Kagame played a leading role in this. During that Rwandan intervention in its neighbouring country, hundreds of thousands of Rwandan refugees fled into the interior of Congo, where they were hunted down by Congolese rebels and the Rwandan government army.

“Those refugees have disappeared and have been largely murdered. But by whom? I do not believe that Kagame has been there continuously with his army. There was a civil war, which is still going on. Kagame is partly responsible for that”.

There are different versions of what triggered the murderous events in Rwanda. Pronk talks is his book about an apparently planned mass murder against Tutsis. In “My Story” written by the Belgian ambassador to Rwanda Johan Swinnen, published two years ago, he says that he never actually had any proof of that. Pronk made his analysis of the events based partly on what preceded the genocide.

“Take the invasion of the RPF army into Rwanda in 1990, of exiles who were in many countries around Rwanda, especially in Uganda. At that time, I had just been appointed a minister. I felt that this invasion was not justified. I was glad at the time that the attack failed. Because then you have to look for a political solution. And for me, the political solution was negotiation between the two parties. I offered to finance those negotiations at the time, on the condition that they keep us informed about the course of these negotiations in Arusha.

“Well, the information I got was that the pressure on the government of Rwanda was bearing fruit and that it was willing to make concessions. There was some willingness to come to an agreement. So, when the plane (of President Juvenal Habyiramana) was shot down, that was a surprise to me. I knew that the RPF was following a rather hard line. What I had not foreseen at the time was that there was internal pressure on Habyiramana to act even harder. All the information that we collected from numerous sources at the time indicated the attack on the plane came from within.

“Kagame denied he was involved, and that was also the conviction of Romeo Dallaire (commander of the UN force in Rwanda), and every member of the UN in Kigali. And other countries too, except France. I wonder if it will ever be established with 100% certainty who shot down the plane. It’s like the question of how John Garang died. And UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöd, and the Kennedy assassination. It’s in that that category”.

Pronk in his book keeps to the argument that the genocide was well planned.

“Yes. I never understood that opinion of the Belgian ambassador, that he had no prior knowledge of it. If I read Dallaire I know there was prior knowledge. Like the buying of machetes and no action being to stop that. The blame lies with (then UN Secretary-General) Kofi Annan, who didn’t take Dallaire’s warning sufficiently seriously. And Dallaire did not just send one e-mail. He constantly put pressure on New York. The DPKO (Department of Peace Keeping Operations) was too scared of the Security Council member states. Dallaire came up with sufficient factual data to indicate something was being prepared. It was not only against the Tutsis but also moderate Hutus. Something large-scale was being prepared. And you cannot kill so many people across the country in such a short time without having prepared anything.

“There were planners. There was a system operating at lower levels to whip people up, and with the radio station, to participate in the terror. In my opinion, that was premeditation. The question remains whether the attack on the plane was part of it.

“Like a journalist, I asked everyone everything. But there comes a point when you must decide, and then you are no longer a journalist. You keep asking the questions, but you have to decide”.

In praise of blood

They were the bloodiest events of the last century, but what exactly happened is still not known in detail. Canadian journalist Judi Rever in her recently published, controversial book “In Praise of Blood” states that Kagame also committed mass slaughter in Rwanda and later in Congo. According to Rever he also killed large numbers of people before, during and after the genocide in 1994.

When I asked him about Rever’s allegations he said: “I have no proof of that. I note that it is larger numbers than I thought in 1994. The massiveness that some now write about, there were no indications of it then”.

Nevertheless, he heard quite quickly in 1994 that not all was right on the RPF side.

“Those indications were pretty shocking. But then the question arises whether these murders were structural and whether that there were many such incidents. Then you end up with a debate over numbers. Kagame admitted that those killings by the RPF happened, but on a much smaller scale. What you are then comparing is on the one hand a preconceived plan to wipe out an entire population group, with on the other an invasion by Kagame’s well-disciplined army during which many reprisal killings took place simultaneously. You should always assume that a lot of harm happens, even by those who support you”.

Kagame seems not to deal mildly with his opponents. In Rwanda, in neighbouring countries and in Kenya and South Africa, opponents have been murdered. In the Netherlands, Belgium and England, his secret service keeps a close eye on dissidents. One of the murdered opponents was Seth Sendashonga, former minister of internal affairs, who Pronk knew well.

“Sendashonga was one of the men I trusted the most. I thought it was very bad when he was dismissed as a minister. And that he was finally murdered in Kenya in 1998. He had written letters to Kagame about bad things committed by the army. He was brave. After his resignation in 1995, I went to Rwanda and told Kagame that nothing should happen to Sendashonga. ‘How dare you’, Kagame answered angrily. But I dared to do that. It was Dutch protection of a sort.”

After that exchange with Kagame in Kigali in 1995 Pronk helped me to arrange an interview with Kagame. Asked about Sendashonga’s dismissal, the president told me: “We had to clean up that mess to be able to continue”. Maybe Pronk’s credit with Kagame had already been exhausted by then. When I wanted to end the interview because Pronk’s plane was waiting for me at the airport, Kagame boasted: ‘We will continue with this conversation, because I am in power here. I’ll stop Pronk’s plane from leaving’.

Despite Pronk’s intervention with Kagame, Sendashonga was murdered.

“Sendashonga left quite quickly for Kenya. I know that he was more and more engaged in resistance. He became the leader of a movement. He was then apparently seen by the RPF as a political danger. It has been claimed, but I had no proof, that he was about to go down the military route. You know the problem in Africa, who is the first to be side-lined and killed? Your close associates! That has happened everywhere. In Ethiopia, in Uganda. Sendashonaga was seen as a dangerous political opponent, as were the others later”.

After nearly a quarter of a century the region is struggling with the aftermath of the genocide. One wonders whether reconciliation is possible after the kind of massacre we saw in 1994.

“That takes four generations. If you have grandparents who can tell stories about that period, it lives on in you. Once when you can’t speak to people anymore who have experienced it personally, it will gradually takes on a different hue.

“That is why I can understand that fear. And the policies that unfortunately are based on that fear. That is the overriding issue for Kagame: preventing the reoccurrence. But that can also make a leader view every deviant sound as opposition. He takes advantage of it. And that is why it is important for leaders to leave power”.

With publications like the one of Judy Rever the question arises whether there are revisionists at work who want to rewrite history.

“I do not call them revisionists. It is true that there are events about which you will probably never fully know the truth. But it must be independent journalists and scientists doing the investigations. Not the political opposition”.

Ethiopia

Kagame was not Pronk’s only controversial ally in Africa. There was also Yoweri Museveni in Uganda, and Meles Zenawi in Ethiopia. It raises a provocative question: did Pronk help dictators into power?

“Of course, I did not help them into power. I have supported them. I already considered Museveni obstinate in the nineties, a rhetorical, long-winded person, only interested in being right. I had already lost my confidence in him. And yes, Kagame, I supported him, as a counterweight to the genocide.”

In 1991, Meles Zenawi’s guerrilla movement conquered power in Ethiopia. Pronk and the intellectual Meles were well matched and they debated developments in Africa in private for hours. After Pronk became a professor at the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, Meles while prime minister did study there and did a thesis for professor Pronk on the “developmental state”, a reflection of the authoritarian Ethiopian management model. Meles had planned to write his masters with a thesis on human rights.

“I have always considered Meles as a example of an better African leader. He said we do not need your help at all, so I did not have many instruments for influencing his policies. At the very last moment, I was incredibly disappointed. That was in 2005, when his army shot civilians because he risked losing the elections. I did not want to see him again, I could not stand it. That lasted until he was very sick in a hospital in Brussels in 2012. At first, I did not dare to visit him there, then I decided to go, but he died suddenly. And now I regret not having gone to his hospital bed. Because I trusted him more than the others.”

Sudan

Pronk’s most frustrating time was perhaps his stint as UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan’s envoy in Sudan. “Even the Vatican is easier to reform than the UN,” he told me there after getting caught up in the UN bureaucracy in Khartoum. He did encounter opposition during his time in Sudan.

“Yes, I certainly did”.

His opponents were in New York.

“That was the DPKO. At first the operation was classified as political affairs. As soon as the peace agreement was signed in Sudan, it was transferred to the peace keeping department and I had to deal with very different people. They did not know Africa, and they were only interested in a few things. And not in peace, really. They were just interested in the military aspects of the operation. I saw the military operation as a step towards stabilization, reconstruction and peace. And therefore, also nation-building. And reconciliation. DPKO is not interested in that.

“The UN bureaucracy in New York was a snake pit. It was harder to consult the bureaucrats in New York than the authorities in Khartoum. Some of my top officials in Sudan had been accused of self-enrichment. As a result, those of us working for the UN in Sudan, felt betrayed by New York. I went to Annan, but he said, ‘I cannot help it. This is how the UN apparatus works”.

The Sudanese military accused Pronk of “waging psychological warfare on the armed forces by propagating erroneous information” on his website on events in Darfur. He was declared persona non- grata by Sudan and removed from the country without fanfare. Did the UN lack the balls to protest it?

“That’s true. After my resignation UN-colleagues asked for a protest letter. A letter was drafted at a low level, but they never gave it to Kofi Annan. They frustrated that intentionally. My successor has been told not to be too harsh towards President Bashir. ”

-Johannes Pieter (Jan) Pronk (May 1940) served as Minister for Development Cooperation on behalf of the PvdA (the social democratic party of the Netherlands) in three cabinets: 1973-1977 (under Prime Minister Joop den Den Uyl), 1989-1995 (Prime Minister Lubbers) and 1995-1998 (Prime Minister Wim Kok). In 2013 Pronk renounced his PvdA membership, citing his unhappiness with its policies development and immigration.

– Pronk is working now on the volumes in which he focusses on his time in Surinam, Indonesia and Sudan.

This article was published in a shorter version in NRC Handelsblad on 3-7-2018